Glass Town

Isabel Greenberg, Jonathan Cape

Oh, this is good. Isabel Greenberg’s earlier graphic novels The Encyclopedia of Early Earth and The One Hundred Nights of Hero played with the building blocks of storytelling, weaving her own folk tales, myths and legends out of familiar building blocks and coming up with something new and startlingly original.

In Glass Town she inserts her singular story-telling talents into the margins of the lives of the Bronte family, and, in particular, their juvenilia. It’s a fictional retelling of how Emily, Anne, Charlotte and Branwell came up with their own worlds Angria and Gondal and how those worlds at times consumed their creators.

Greenberg has the Brontes interact with their creations. They step from the grey, cold confines of 19th-century Yorkshire into the vivid colour and storybook design of their imaginary worlds.

The result is a wonderfully moving exploration of the line between creator and creation. And mortality and immortality, for that matter.

It is also another reminder that Greenberg is one of the most singular and imaginative graphic novelists we have.

Year of the Rabbit

Tian Veasna, Dawn & Quarterly

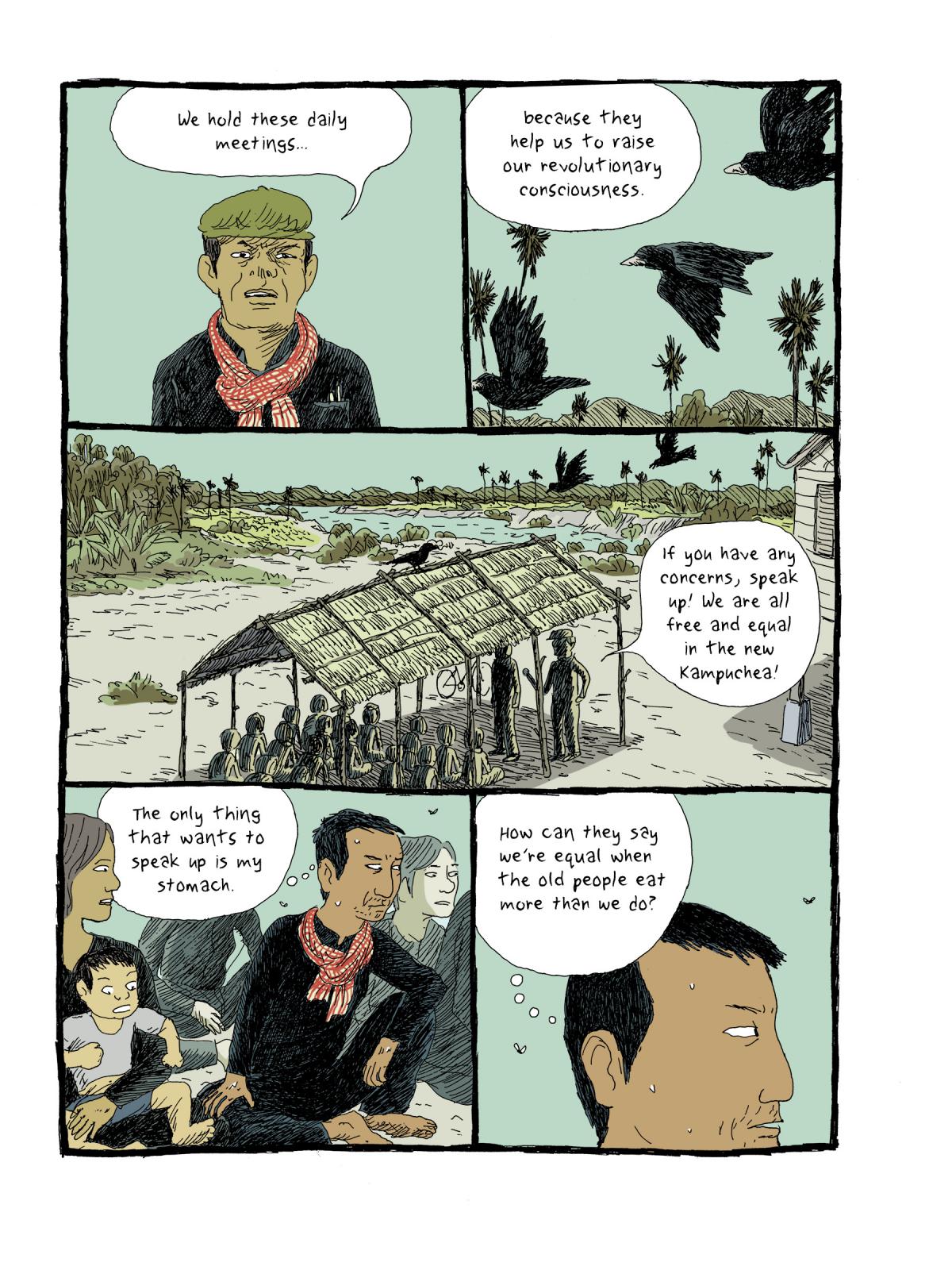

Tian Veasna was born in 1975, three days after the Khmer Rouge seized power in Cambodia. His parents had to leave the capital Phnom Penh to work in the fields and, until they moved to France in 1980, were at the mercy of a regime that sought to destroy traditional ideas of culture and society and quickly parlayed that into destroying people. The regime killed millions of its own citizens.

Veasna’s father was a doctor and so immediately suspect. He had to hide his identity as he and his family coped with the threat of informers and the real fear of starvation.

In Year of the Rabbit Veasna lays out what it took to survive against that hellish backdrop. His cartooning has a scratchy simplicity to it perhaps because clarity is what is needed here. The result is full of horror and a small dash of hope.

The Man without Talent

Yoshiharu Tsuge, New York Review Comics

More scratchy simplicity. Yoshiharu Tsuge is one of Japan’s most revered cult manga creators, part of the 1960s avant garde movement in the form. He has never been published in English before this-semi-autobiographical story of a man at the end of his tether.

It is a graphic novel that flirts with the details of Tsuge’s own life. In the story his stand-in is Sukezo, a manga artist who has given drawing up to sell stones on the banks of the Tama river. It is not a career with prospects. He passes the time conjuring up get-rich-quick schemes, none of which have any prospect of getting off the ground, while his wife hands out fliers to keep them in food.

Amid this misery Sukezo (and his creator) begin to pay close attention to the world around him, the flora and fauna, the weather, the people who are in a similar position to him. “If the Man Without Talent is primarily a portrait of a middle-aged man and his family,” Ryan Holmberg writes in his introductory essay, “it is also a portrait of a place: Chofu and the Tamagawa river that forms the town’s southern border.”

It’s in the way real life rubs up against the beauty of the world that makes this so compelling.

Third World War

Pat Mills and Carlos Ezquerra, Rebellion Publishing

Rebellion’s current campaign to republish some of the classics of British comics reaches an interesting point with Third World War, Pat Mills and Carlos Ezquerra’s strip from the short-lived Crisis comic that Fleetway published between 1988 and 1991.

While 2000AD gave a satirical slant on the culture and the politics of the day safely draped in distancing sci-fi, Third World War was a more explicit, more direct in its views.

More than three decades on, it represents an archaeology of leftist politics of the time. Although set in the near future (a near future that in 2020 is now in the rear-view mirror) the strip draws on many of the key issues of the time for the progressive left, in particular the clash between First world and Third that was going on in Latin America during the 1980s, in particular in El Salvador and Nicaragua.

Mills weaves South American death squads and facsimiles of the Argentinean mothers of the disappeared into a strip that investigate the impact of multinationals on third world countries and the way they used their corporate muscle to wield commercial and political influence via aid and military intervention.

It’s the story of teenager Eve Collins who has been drafted into an organisation called FreeAid who are attempting to win over hearts and minds in the Third World. Mills used Collins and her fellow draftees as sounding blocks to spell out the insidious and sometimes in-plain-sight work of multinationals in opposition to the needs and rights of Third World citizens.

The result is unafraid to be polemical. Mills’s politics are not difficult to pin down. He is not aiming for subtlety or nuance here. He wants to bang you over the head with the reality of the politics of food.

It makes for punchy reading if you can take the lecturing tone (Ezquerra’s art comes to its aid here).

What is interesting is that here is a strip that has a young woman of colour at the heart of it at a time when that was by no means common. That it’s not even commented on is one of the strip’s smartest moves. He also allows Eve to be flawed and contradictory. At times, she doesn’t live up to her own political outlook which makes her satisfyingly human rather than a walking political position.

There are inevitably some anachronisms. In Third World War the Troubles in Northern Ireland and apartheid are still ongoing and the size of the television sets – TV being the main way propaganda is spread - are tiny (it’s always the small things that trip up future visions). There’s also one spot of gratuitous comic book nudity that feels out of touch with the book’s otherwise progressive politics.

But anyone who was a student in the late 1980s will recognise much of the conversation that Mills is having here.

Bowie: Stardust, Rayguns and Moonage Daydreams

Michael Allred & Steve Houghton, Insight Editions

It was always a matter of no slight irritation that back in the day second-division glam rock no-marks like Alice Cooper and Kiss got their own comics and the real gods of Glam (Roxy, T-Rex and, yes, David Bowie) did not.

Three decades on Bowie is finally getting his own comic-book incarnations. Back in 2017, French-Tunisian cartoonist Nejib channelled Bowie’s pre-Ziggy days through a New Yorker filter in the gorgeous, swoony Haddon Hall and now Michael Allred and Steve Horton bring a Marvel Comics vibe to the same material.

Retelling the story of Bowie from Space Oddity to Ziggy Stardust, Bowie: Stardust, Rayguns and Moonage Daydreams is a fan’s eye view of the (pre) Thin White Duke. It’s a lovely, loving gather-up of Bowie trivia (did you know that Bowie and the Spiders of Mars once spent a night in the same Edinburgh hotel as the members of Monty Python?) that glories in Allred’s almost tactile clear-line cartooning. The moments when Bowie comes face to face with all his various incarnations is like something out of Jim Starlin’s most fevered dreams.

Bad Island

Stanley Donwood, Hamish Hamilton

Best known for his work with Radiohead and author Robert MacFarlane, artist Stanley Donwood goes it alone with Bad Island. The result is a flicker book of images that detail the evolution of an island in the middle of wild seas from primeval times to post-human. Spoiler. We humans are poor tenants. Not a happy story, then.

What Bad Island does offer, though, is Donwood’s bold, strong line-making. He’s particularly great at waves. We want to dive in, but we’re not sure we’d be able to get back out if we did.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here