Double Lives: A History Of Working Motherhood by Helen McCarthy

Bloomsbury

IF you’re a working mother, spinning plates, especially in these times of lockdown homeschooling and possibly also homeworking, it’s doubtful that you will have the time to pay full attention to this hefty, ground-breaking tome which sweeps through the history of working motherhood. That’s a pity, because historian Helen McCarthy’s thorough and patient work puts where we’re at in perspective, and perspective always helps.

Double Lives isn’t just a book about women and work – it’s about mothers and work. It’s about the two roles many women occupy through their lives and the ways in which they have been valued by society, or conflicted in their own existences. I wondered if it might alter the way I saw myself as a working mother, and it did, though mostly be reminding me of some of my own forgotten conflicts, and their place in history. It reminded me, for instance, that I’d tried to reconcile two paths, by trying to go back to work, yet also practicing long-term breastfeeding at the same time. I felt that my role, physically, as mother to these two young lives was deeply important, but I also loved my work, and struggled to reconcile those two.

It was also a reminder of a feeling I often get when considering women’s rights history – that we have both progressed at startling speed, yet also at some level seem to be treading water, stuck with the same ideas, drowning in the same intense expectation and pressure that exists around women and motherhood.

What’s most fascinating is the early history documented by McCarthy, which on one level shows how far we have come. She, for instance, quotes how in the 1940s, responding to the Ten Hours Bill, Lord Ashley declared that “the employment of mothers disturbed ‘the order of nature and the rights of labouring men”. Back in the 19th century, she describes, mothering “was seen as a service to the state and duty to the Empire”. Such views now seem archaic in the UK, though not in all parts of the world – Venezuela’s president, for instance, recent encouraged women to have six children each “for the good of the country”.

What also features throughout the whole of this history is the way that working motherhood, and all motherhood, is subject to a class divide. Working-class women’s motivations for working are also often caricatured. For instance, McCarthy shows that the idea that in early 20th century Britain, it was not only privileged women who gained satisfaction from their work, is not entirely true. Nor was it always the case that women worked in order to get enough to survive – sometimes it was for the extras.

The desire to go out and work, rather than be at home with children or enjoy the satisfactions of being a homemaker, she shows, was deemed from those early years to signify a bad mother. “A marker,” she writes, “was set down in the late nineteenth century between the ‘good’ mother who earned only because she had to, and the ‘bad’ mother who went out because she wanted to. This dichotomy would prove enduring.”

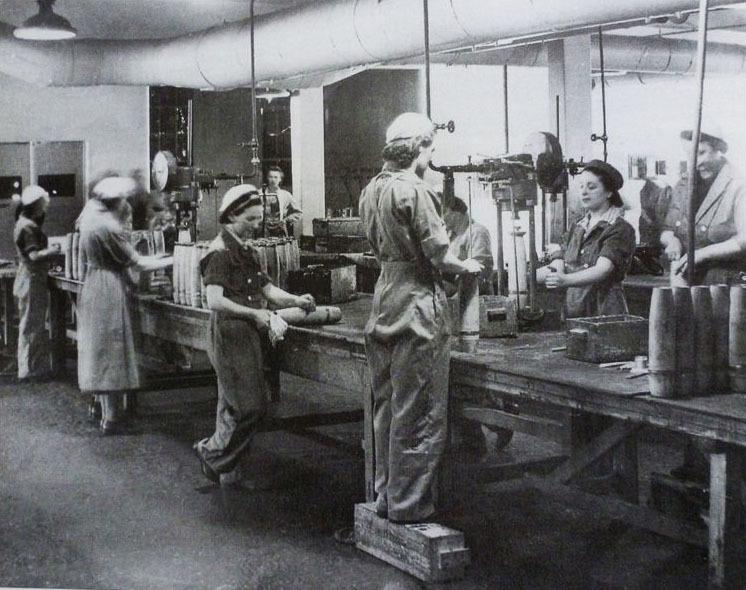

It’s also a story of often conflicting pressures and values. When the First World War arrived many mothers were called upon to work as the female workforce grew by 1.25 million between August 1914 and Armistice Day. Mothers, in that period, would often have to do a double shift of paid factory work and unpaid housework. “The war,” McCarthy writes, “created a peculiar ideological landscape for the working mother. She was welcomed into factories and celebrated publicly for her service, but at the same time because the object of intense official scrutiny in which her ‘higher’ duty as life-giver and nurturer was continually invoked.”

This is a story of legal changes – or marriage bars lifted, maternity payments, family allowances, equal pay legislation – and economic developments. It’s a story too of those who campaigned for greater financial support for women in their role as mothers.

What is striking is that the juggling of work and homelife is a struggle that has a long history. McCarthy quotes Mass Observation research which reveals the voices of working women speaking during the period of war-time mobilisation. One mother of two, with a part-time factory job and household duties, says, “You know what it is with children. You’re never finished. You’re always on the go. And soon it’s time to wash them, give them their supper and put them to bed. There isn’t much of an evening left. I try and do a little knitting in the evening, I knit all the socks and jerseys. Sometimes n the evening I get fed up and want to pity myself. But I can’t really. There must be many fixed the way I am.”

But that work has brought many women pleasure. Mass Observation research also showed that following the end of the war, most women, longed for conventional lives as housewives and mothers, with the exception of older part-time war workers who had enjoyed their four-hour stints in the factory “with something approaching an ecstasy which neither strain nor fatigue can spoil.”

It’s fascinating to read the period that covers my own mother’s raising of myself and my four brothers – mostly done as a homemaker and farmer’s wife. McCarthy’s exploration of the 1970s features Shirley Conran’s Superwoman, with it’s advice that “life’s too short to stuff a mushroom”, and intention, as McCarthy puts it “to give women freedom to enjoy life: hours not spent on housework could be redeployed to more pleasurable, meaningful activities.” She looks also into the growing ranks of women bringing up their children alone, describing them as the “most stressed out working mothers of the 1970s”.

Between then and my own mothering years was Allison Pearson’s I Don’t Know How She Does It, published in 2002, with its high-achieving middle-class career woman Kate Reddy, who some how came to define what it meant to juggle working motherhood, though, as McCarthy points out, a far more typical experience of the time was “the mother employed part-time in cleaning, catering, retail or low-level office work, who had no money to spare for expensive childcare or lunchtime dashes to the LK Bennett sale”.

By the time I became a mother, McCarthy outlines, income inequality and social mobility had stalled, and as a result women’s experiences of working and living had become drastically different. “These social cleavages were reflected in the fracturing of feminist activism, where it seemed increasingly impossible to build a unified movement amongst women in such vastly different material circumstances.” Working-class and immigrant women would not have the same experience as the wealthy. But, she writes, there were ways in which the Kate Reddy character would have resonated even for those less privileged. “Her emotional conflicts and physical exhaustion were more widely shared. The popular clichés of women spinning plates, juggling balls and battling across the clock struck a chord because many mothers felt that their lives were defined by tension and stress: the stress of competing for careers designed for men with full-time wives; the stress of looking after elderly parents, staying in touch with friends and remembering important birthdays and keeping everyone happy.”

One of the great things about McCarthy’s book is that it is resolutely non-polemical. She is a calm and measured guide, digging through the voices of the past. “It is not the historian’s job to reveal essential truths about women’s desires, past or present, or to generalise about paid work as either ‘good’ or ‘bad’ for mothers, families or the nation at large,” she writes.

But that’s also what can make the book hard work at times. I found myself always looking for the message, and frustrated by ambiguities. However there are themes that come through – the idea that this journey was really towards autonomy, particularly financial autonomy, and out of domestic servitude. Through Double Lives, I gained a glimpse of the ways in which my own path through working motherhood has been coloured by the ideas of my times. The working mother has, of course, now become a norm, and, with it, more recently, the domestic father wheeling a pushchair or carrying a baby in sling. In many households batons are being passed the whole time. But women still feel many of the pressures of ideals of motherhood that haunt us from the past. Examining them helps us shake and reshape them.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here