John Neil Munro

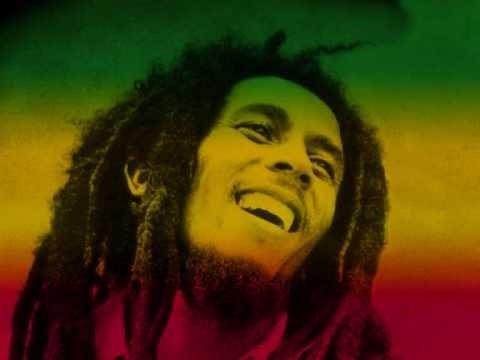

THEY were the nights when the sunshine sounds of Caribbean reggae lit up grey old Glasgow town. Forty years ago this month, the great Bob Marley played his only concerts on a Scottish stage.

I was lucky enough to be there, perched precariously in the front row of the rickety old upper circle of the Glasgow Apollo, with my friend Ann from Gaborone.

There were 3500 others there that night (July 10, 1980), and the same again the following evening – and we all saw something special on those hot July nights.

Many in the crowd were wearing T-shirts and scarves with the colours of Rasta – red, yellow, and green.

The air in the Apollo was thick with a pungent smoke that probably didn’t come from Woodbine cigarettes.

For me, and I suspect many others who had been weaned on a diet of 70s glam rock and heavy metal, it was the first time we had seen a non-white performer.

Marley, the seven Wailers – two guitars, two keyboards, bass, drums, and percussion – and the I Three vocalists – Rita Marley, Judy Mowatt and Marcia Griffiths – made a joyous, exotic sound.

Billy Sloan, who was covering the gig for the Record Mirror, summed it up as “three hours of peace, love and good music” – and he was right.

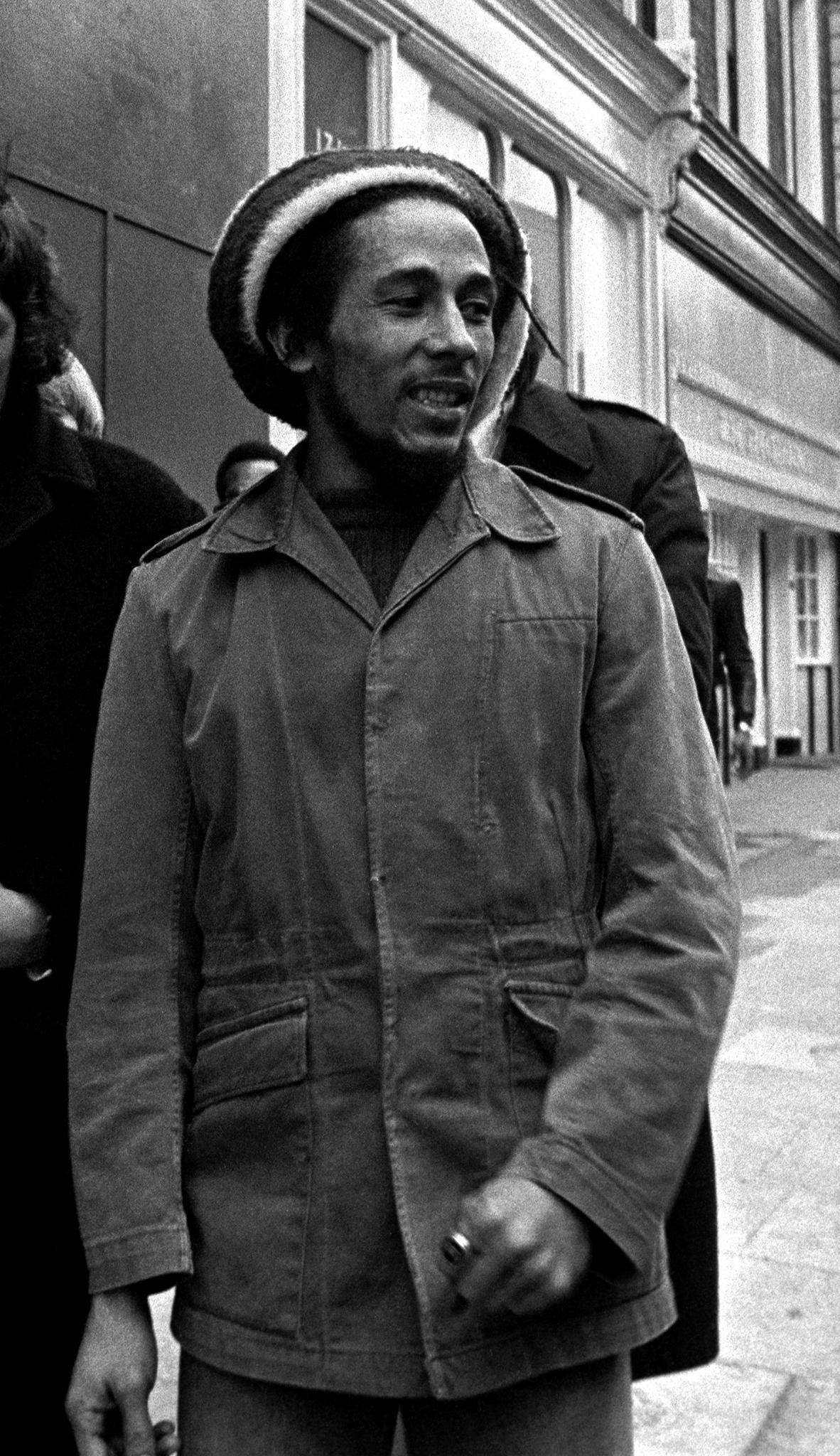

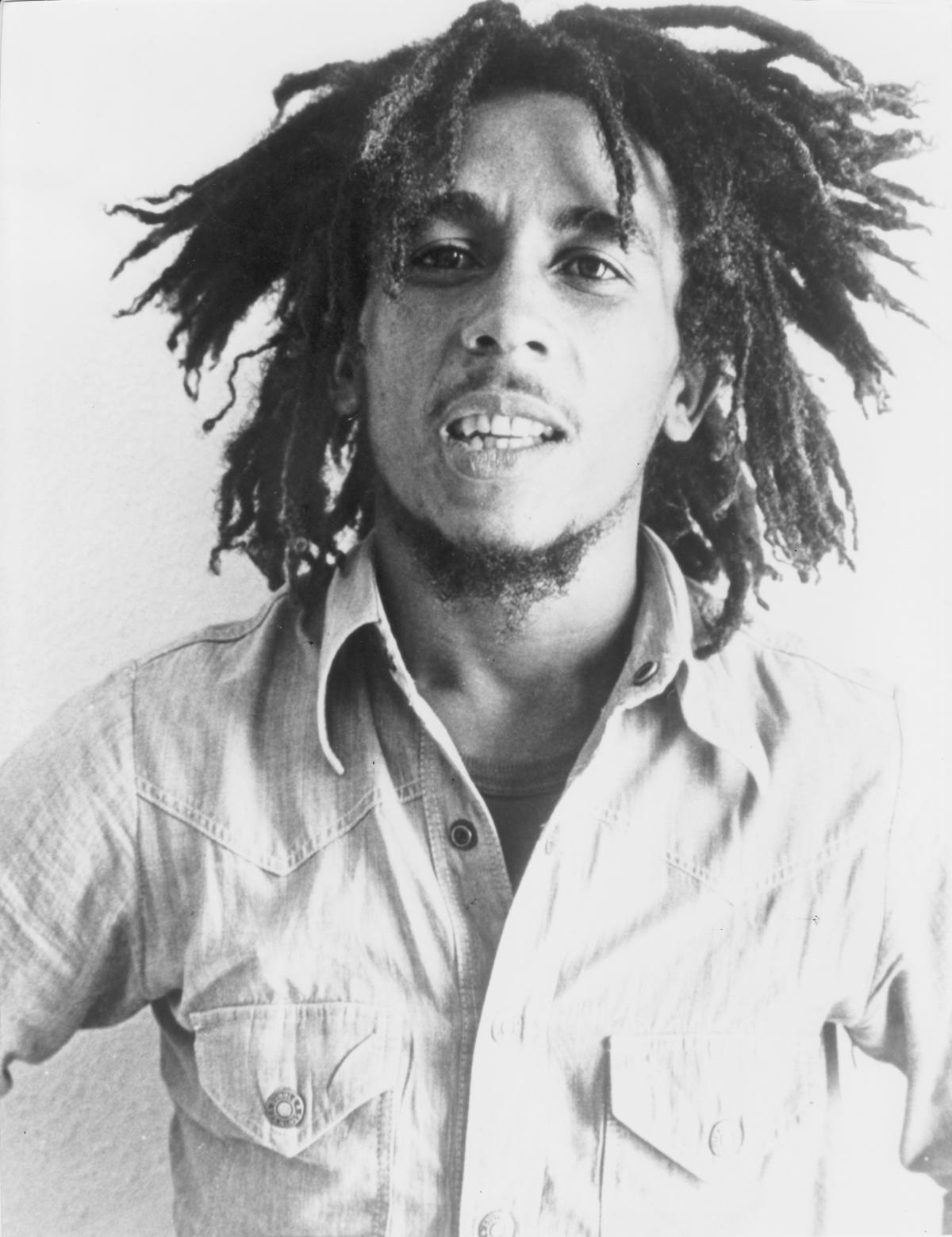

From our vantage point up in the gods of the Apollo, Marley initially looked frail, his small frame crowned by a heavy weight of dreadlocks.

But from the moment he took to the stage, delivering a beautifully nuanced Natural Mystic, he seemed energised and transfixed.

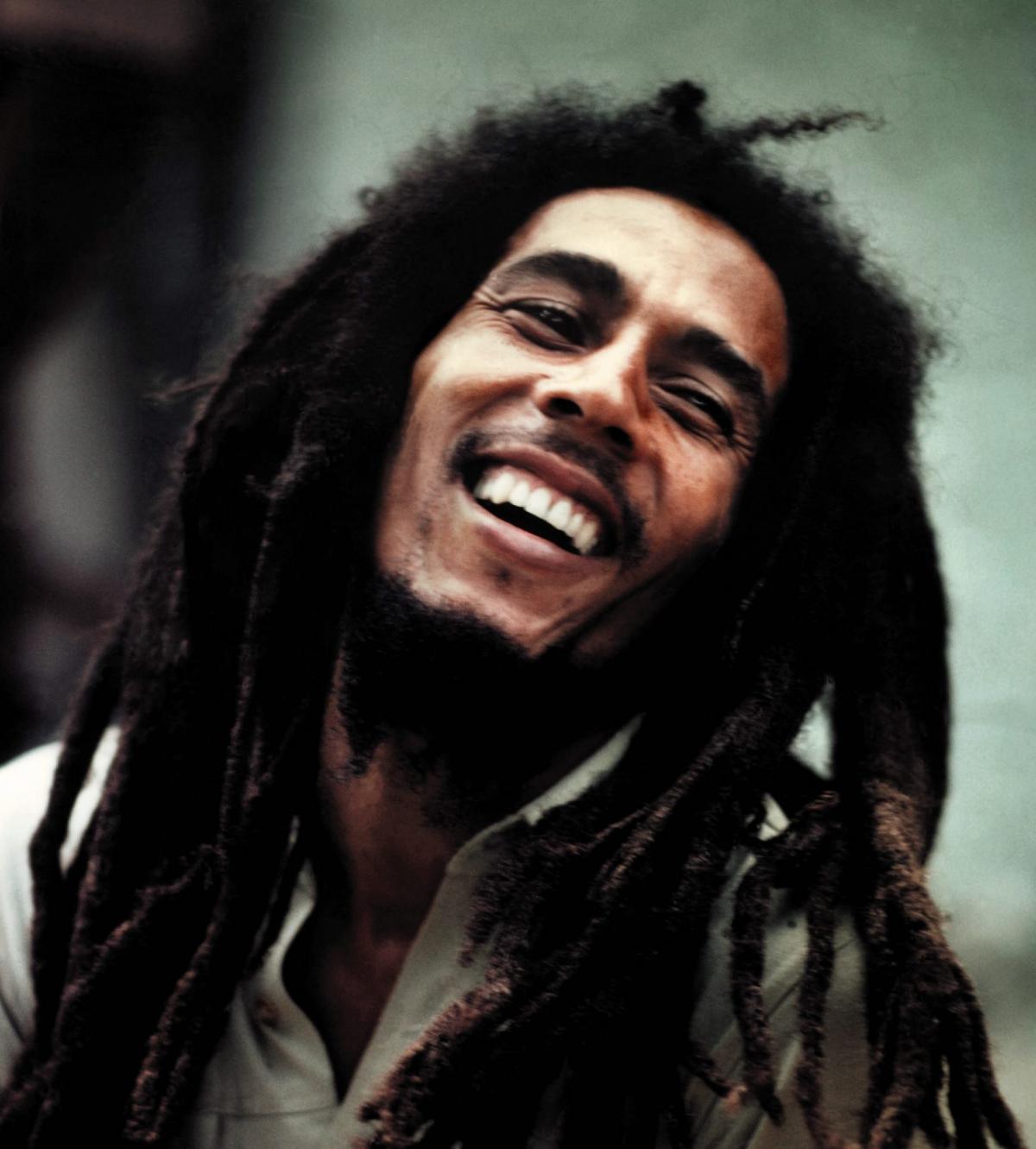

Bathed in sweat, his eyes often shut as he sang, he gave an exuberant performance for the whole show, drawing huge cheers from the capacity crowd as he danced on the spot – knees-up style – during Jamming.

At times he seemed exhausted and in pain, clutching his forehead theatrically during an impassioned No Woman No Cry.

The most memorable moment of all, though, came after the intermission, when Marley walked back on stage alone, armed only with his acoustic guitar to give a sincere, beautiful, and bare rendition of Redemption Song. One by one the band joined in behind him.

For the final number of a seven-song encore, Get Up Stand Up, Marley led us in a mass singalong which could probably be heard down in the Gallowgate.

Also at the Apollo that night was journalist Frank Morgan, who was working at the Evening Express in Aberdeen at the time.

Aged 24, he had already seen an impressive list of live acts ranging from The Rolling Stones to The Undertones.

The night he saw Marley still stands out in his memory though.

“I'll never forget the palpable air of excitement before we got into the Apollo. There was a buzz even on Renfield Street as I arrived from Aberdeen with my then-girlfriend and an old mate from school.

“I had managed to get us great seats in my preferred place, five rows behind and slightly to the right of the sound desk in the circle. Given the height of the Apollo stage it was a grandstand view.

“The band came on and began a chug-along reggae beat, the I-Three backing singers came on and began to chant "Mar-ley woaaaahhh" over and over and soon the entire audience was singing along.

“This went on for several minutes when the man himself came skanking on from the left-hand side of the stage. The noise was deafening as the Apollo went crazy.

“My first impression was what a small, slight figure he cut. But I doubt I've ever seen such a hard working performance from an established star. The energy was so strong you felt you could have reached out and touched it.

“At the sound desk, a giant Rasta in trademark green tracksuit and enormous dreads, was smoking a spliff about nine inches long.

“The whole show was magnificent and the choice of set nigh-on perfect…all the biggies were in there, like No Woman No Cry, Exodus, Natural Mystic.

“After the show, many of the audience gathered out front of the Apollo and, even then, there was an atmosphere like our team had just won the cup. We talked about nothing but the gig for at least a week after.”

The impression we all got that evening was of Marley as a global superstar with a long successful career ahead of him.

But sadly, he would only play a handful more concerts. Unbeknownst to us all, Marley was already in the grip of a cancer that would kill him within a few months.

Marley and the Wailers had arrived in Glasgow as part of the Tuff Gong Uprising tour – a long, arduous six-week trek through 12 European nations. It was the biggest tour in Europe that year, playing to over a million fans across the continent.

Over 100,000 saw Marley play at the Crystal Palace Garden Party in London and also at Dalymount Park in Dublin.

But even these shows were dwarfed by a massive event in Milan on June 27 when an estimated 180,000 rolled up to see the legend.

The Uprising album was the soundtrack of our summer. It reached number six in the UK charts. Two singles – Could You Be Loved and Three Little Birds (from the Exodus album) also, made the Top 20 here.

When the last date was done, the band returned to London to rest up, but already insiders were concerned about Marley’s health – he looked gaunt and his trademark beaming smile was missing.

Despite this, he and the band soon had to focus on another gruelling leg of the tour – this time in America, supporting Stevie Wonder. It was to be a crucial attempt to finally crack the US market – which strangely had been until then unconvinced by Marley’s music.

A lucrative deal with Polygram reputed to be $10 million for five albums – including a $3 million advance – was on the table.

In the event, the band only played five shows on the American leg of the tour, culminating at the Stanley Theatre in Pittsburgh on September 23. It was to be Marley’s final concert appearance.

He had hinted in August 1980 of the agonies that were wracking his body. “I got a pain in my throat and head and it’s killing me. It’s like somebody’s trying to kill me. I feel like I’ve been poisoned. And something's wrong with my voice. I’ve never felt like this before in my life.”

After collapsing while jogging in New York in September, Marley, who a few years previously had been treated for cancer in the toe, was now diagnosed with a malignant brain tumour. He was told he had weeks to live – the cancer was spreading to his lungs, liver, and stomach.

As a last resort he was flown to West Germany in November for treatment with cancer specialist Dr Josef Issels at his clinic in the Bavarian Alps.

The final months of 1980 saw wild contradictory rumours about Marley’s health, culminating in a hoax story in December, when newspapers and radio stations throughout Europe reported that he had died. His record company issued repeated statements, denying even that he was in hospital and claiming that he was looking to record and tour again soon.

In March 1981, Marley issued one last defiant message from Germany. “Like so many other patients who have come here, I was given up by the doctors to die. Now I know I can live. I have proved it…I’ve gone inside myself more. I have had time to explore my beliefs, and I am stronger because of it. I believe he is the best doctor a man could have. He gives me strength to live.”

At the end of March, the News Of The World said that Marley was able to walk unaided and that his wife Rita believed he was on road to recovery.

But in April photos appeared in the press of Bob, looking frail and weak, with his trademark dreadlocks shorn. He was pictured studying the bible with his mother, Mrs Cedella Booker. The end was near.

Marley died, aged just 36, on May 11 at the Cedars of Lebanon hospital in Miami. Just 304 days had passed since those triumphant, unforgettable nights at the Glasgow Apollo.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel