THE Roaring Twenties in America. If you had money everything was in play.

“Fuelled by the rising American stock market and the ferocious gearing up of industry, the Twenties was emerging as a decade of mass consumption and international travel, of movies, radios, brightly coloured cocktails and jazz,” Judith Mackrell writes in her book Flappers. “It was a decade that held out the promise of freedom. For women, that promise was especially tantalizing.”

Women in the US got the vote in 1919, and in the decade that followed “the new woman” emerged. Flappers were seen as wild, dangerous, even immoral by some. Many, though, were just embracing new freedoms in dress and behaviour. “You can’t dance the Charleston in a corset,” as Trina Robbins notes in the introduction to her new book, The Flapper Queens: Women Cartoonists of the Jazz Age.

Flappers were to be found in films, in the novels and stories of F Scott Fitzgerald and, as Robbins’ book reveals, even in newspapers’ funny pages.

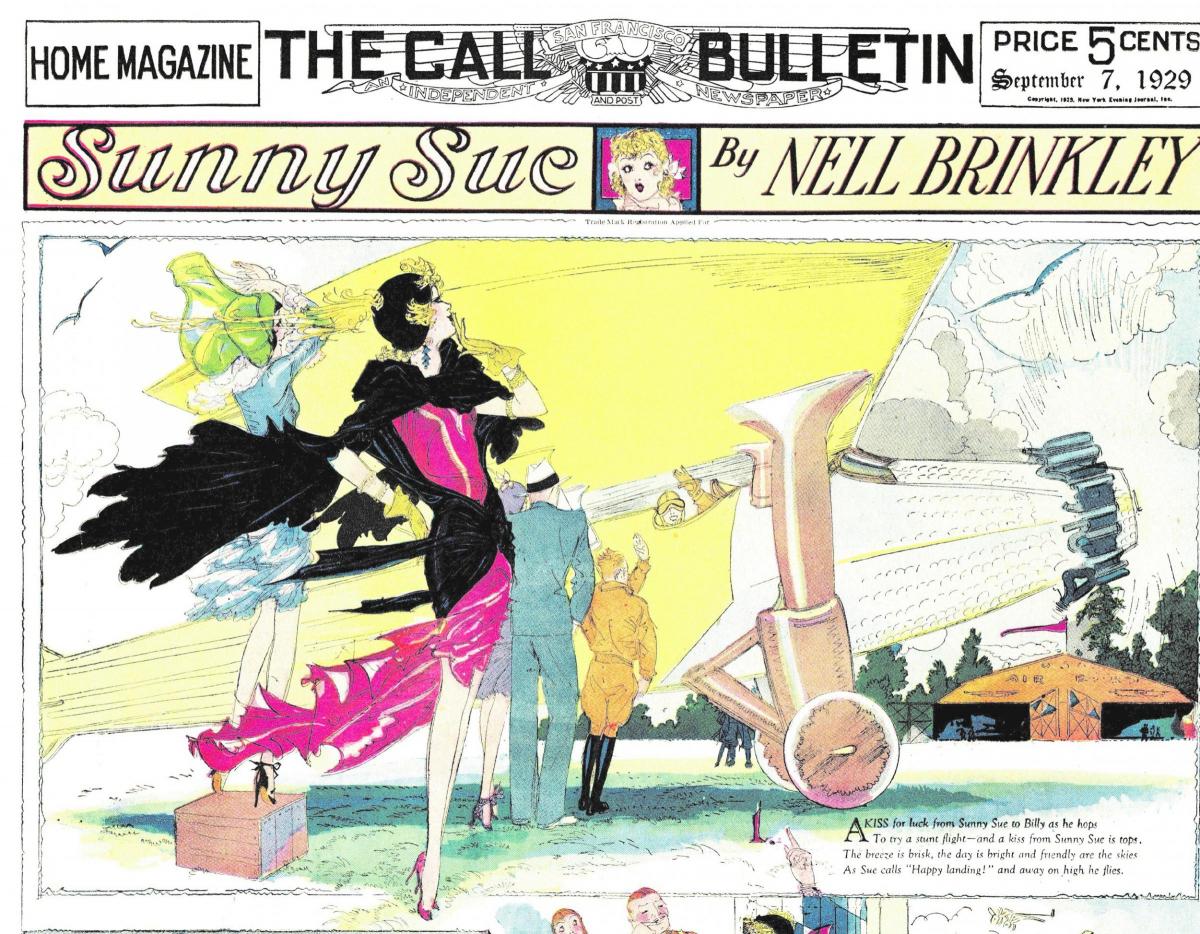

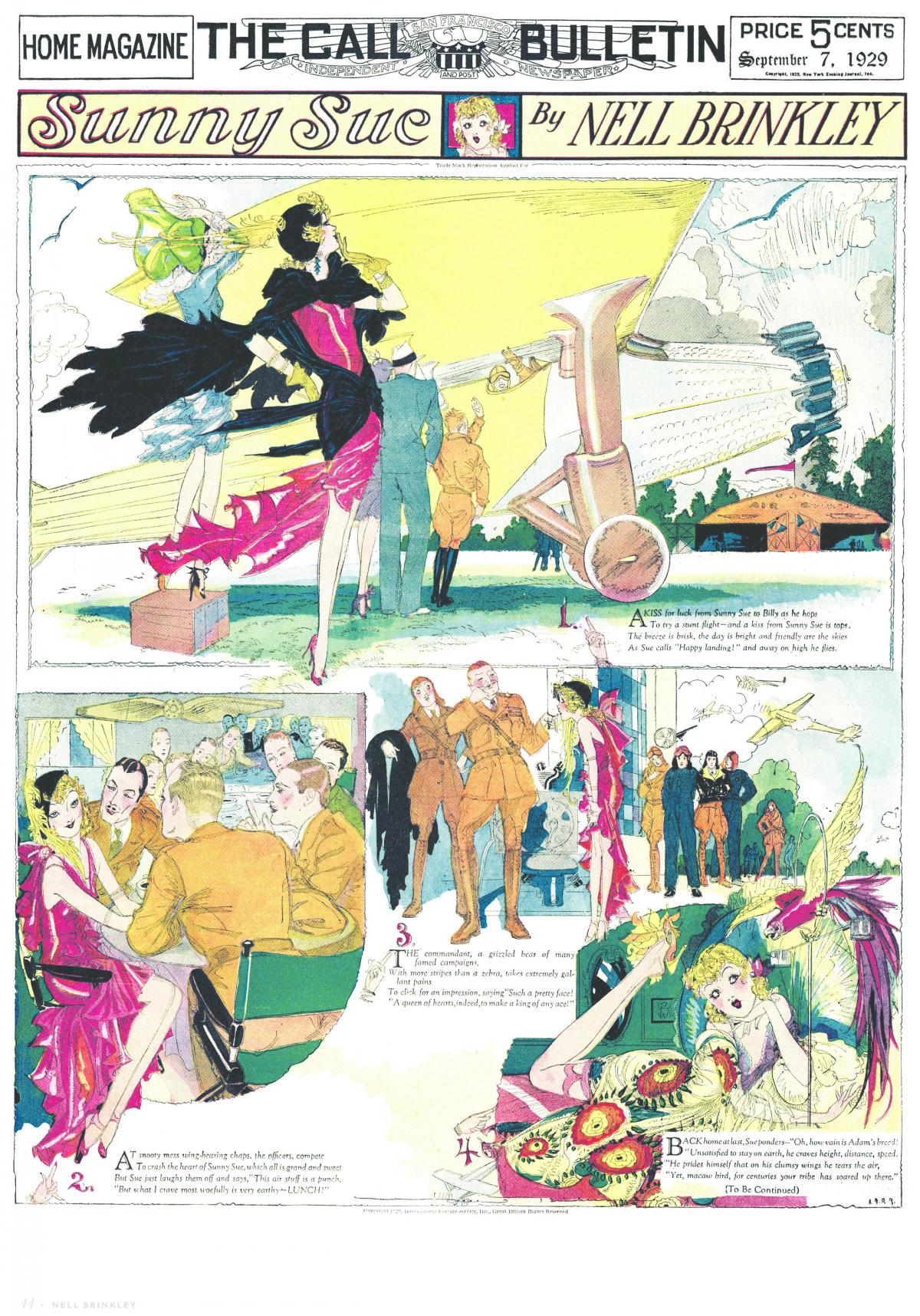

In The Flapper Queens, Robbins looks back at the work of a number of female cartoonists of the era who epitomised ideas of the new woman. Nell Brinkley, Eleanor Schorer, Edith Stevens, Ethel Hays, Fay King, Virginia Huget and Dorothy Urfer all worked on the comics pages of newspapers, bringing vivid colour and humour to their work that often wouldn’t have looked out of place in the pages of Vogue or Vanity Fair.

Robbins who made her name as an underground cartoonist and as a comics “herstorian” has been one of the most eloquent and dedicated chroniclers of women cartoonists. Here, Robbins talks to Graphic Content about The Flapper Queens, their popularity and their creative freedom:

Trina, what was the spark that lit your interest in The Flapper Queens? Had you always known of these cartoonists?

I already knew about most of these cartoonists and felt that they hadn't had the exposure they deserved, because when I wrote about them in my herstory, Pretty in Ink, I only had the space to give them a paragraph or two, or at most a page. Others I found out about. I was very lucky when Rob Stevens contacted me about his great aunt Edith St Stevens - what a pleasant surprise. And I had known Eleanor Schorer only as a Brinkley-style artist, but researching old newspapers I found her later flapper cartoons, and they were completely different from the flowery art she had done 10 years earlier.

You’ve concentrated on a small number of cartoonists here. Were there many more?

There were many, many more! I didn't want to wind up with just a few paragraphs on each woman, so I picked the most outstanding to include in the book.

How was their work used in newspapers?

The full-colour pages were usually the first pages of the Sunday supplements, but the black-and-white cartoons were from the daily funny pages.

How popular were they?

Immensely popular. Nell Brinkley, the queen of them all, was collected and saved by mostly female readers, often pasted in scrapbooks. Young girls would paste them in scrapbooks and colour them in.

How were women cartoonists seen at the time? And how did that reflect the position of women in American society in the 1920s?

It was never considered unusual for women to be drawing comics. Even before they got the vote, the newspapers were full of comics by women, like the amazingly prolific Grace Drayton, or Rose O'Neill's kewpies.

Did women cartoonists have more agency at that moment in time than cartoonists in the subsequent decades?

Do you mean could they draw what they wanted? Certainly. There was no set style for how cartoonists had to draw in order to be published.

Is it fair to say that women cartoonists wouldn’t have the same freedoms and same visibility they had in the 1920s until, well, when? The 1960s? Now?

More like, until this century. Yes, starting with the 1960s, women could draw how they wanted in underground comix, but the underground field was very male-dominated, and in mainstream comics women didn't have a chance in hell. This century is when the field started to open up, and you didn't have to draw superheroes in order to be published.

The work of Nell Brinkley, Ethel Hays and Virginia Huget in particular look as if they owe as much to fashion magazines as comics. Nell wasn’t keen on the idea that she was doing comics.

I think Nell thought of comics as something crass, but she obviously changed her mind by the 1920s. As for fashion, women simply like clothes. (I do!) So why not draw cartoons about clothes? (I do!)

How much were these cartoonists reflecting their own lives? (Huget was in her twenties when she started and did include working-class girls in her cartoons, so presumably that was the world she drew?)

Virginia Huget was younger than the others, and because of her youth may have been more aware of working women. In other cases, I think they were reflective of the life they saw around them, which had changed so much since the First World War.

Were they considered risque?

By contemporary standards, not risqué. But they were reflecting the new sexual freedoms, which to us are pretty mild, but were very revolutionary by their standards.

What do these cartoons tell us about 1920s American womanhood, do you think?

I think the young women they depict (and the artists themselves) were delighted by their new freedoms and the new sexual revolution, and it shows in their cartoons. Even now, looking back on it, comparing, say, 1915 with 1925, it's dizzying to see how much their lives had changed. Gone were the corsets, in their place were short skirts and short hair. Drinking, smoking, wearing makeup, all of which 10 years earlier would have branded them loose women, were suddenly perfectly okay, and they thoroughly enjoyed it all!

The Flapper Queens, by Trina Robbins, is published by Fantagraphics Books

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here