EVERY now and then an impassioned but polite stushie breaks out on the letters page of The Herald over whether it is correct to refer to the monarch as Queen Elizabeth I, as some Scots do, the nation not having a Queen Elizabeth until after the 1707 Act of Union, or Queen Elizabeth II.

In his new three part documentary, New Elizabethans with Andrew Marr (BBC2, Thursday, 9pm), the presenter jumps in within the first few minutes to declare her Elizabeth II. As any viewer of his Sunday morning interrogations of politicians knows, it is a brave soul who questions the fact checking prowess of Scotland’s other Andy (the first being Mr Murray of course).

Marr has plenty to be getting on with as he sets out his ideas for the series, the central one of which is that the UK has undergone profound change since the Coronation of 1953, a lot of it for the worse, but some for the better. To illustrate his points he chooses a series of individuals, his “New Elizabethans”, who in some way defined their times or pointed a way to the future.

His list of New Elizabethans is long and diverse, stretching from Scottish trade unionist Jimmy Reid and Sir David Attenborough to The Body Shop founder Anita Roddick and celebrated cookery Elizabeth David, who introduced colourful mediterranean fare into the stodgy, beige diet of postwar Britain.

As is usual for Marr, canny journalist that he is, there is a book to accompany the series, Elizabethans: How Modern Britain Was Forged, that will doubtless be on the Christmas wish lists of many. But the era really comes alive on screen through archive and contemporary footage.

He has picked out some great stories, some less well known than others. On the whole there is not much that is new, but Marr’s packaging of the information is slick and compelling and his arguments persuasive. Fittingly enough, he identifies Britain’s creativity, plus marketing and PR prowess, as some of the areas in which we continue to be world beaters.

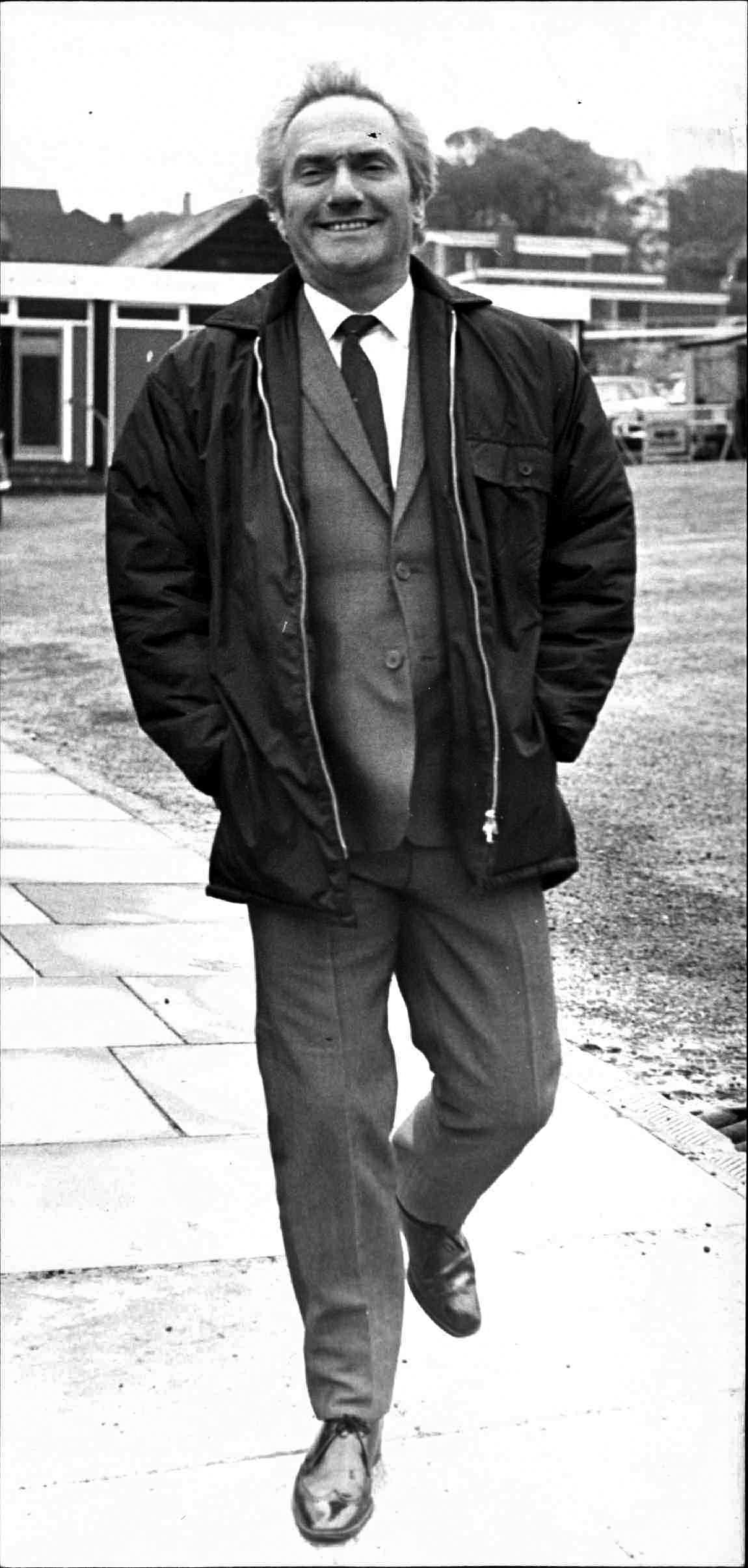

Ooh, you are awful but I like you. Hello Honky Tonks. The toothy vicar. Man-hungry Hettie. Lampwick the spiky pensioner. Depending on your age, such characters and catchphrases will either draw a complete blank, or spell out the name of one entertainer in big showbizzy lights: Dick Emery. Once the king of Saturday night television, he is rarely heard of today, something Dick Emery’s Comedy Gold (Channel 5, Sunday, 9.30pm) seeks to put right. Dubbing him “comedy’s forgotten man”, Ricky Kelehar’s 110-minute film traces a direct line from the comic who survived a postwar stint at the Windmill Theatre in London (home to nearly nude models), where nobody came for the comedy, to performers of recent times.

One contributor says there’s more of Dick Emery in modern comedy than many people realise, but they don’t know it because his shows are not repeated. Among those on the trail he first blazed with character based comedy are Little Britain, The Fast Show, and Catherine Tate.

Fast Show writer and performer Charlie Higson knows better than most the power and tyranny of a catchphrase and a character. It was something from which Emery suffered: the comedy characters brought him riches and fame, but he could never escape them, no matter how much he wanted to be seen as a serious actor and make it in film. Television made him and television would not let him go.

This is a fascinating portrait of a performer from another age. The early years, and his spell in the RAF, are a tale and a half on their own. He was a doting son throughout his life, but his many wives, girlfriends, and children, had to be content with scraps of his time. He would race in and out of lives at the speed of one of his beloved motorcycles. “He was an odd man,” says one son.

The many clips show why Emery’s work fell out of favour. Time has moved on, and attitudes with them, and what might have seemed funny then looks crass today. Yet the film finds defenders, sometimes in surprising places, who beg to differ that Emery’s broad comedy was beyond the pale. His gay character Clarence, for instance, is held up as a proudly “out” man.

Whether you buy that or not, there’s no doubting Emery’s impact on popular culture, then and now. Despite his wealth, most of which he spent, and his many partners, his was a sad life in a way. One of the jewels of the film is a never seen here Australian television interview in which the presenter tries to dig a little deeper, a place Emery was never keen to go. “I consider myself a commodity, like a tin of beans,” he says finally.

When Emery died in 1983 his passing made every front page and national news bulletin. What a world away it all seems now.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here