SO often have the last rites been read for painting as an art form that anyone who knows their cadmium yellow from their cobalt blue has long since stopped listening.

Veteran artist Alexander Moffat, known universally as Sandy, is one of them. And even if he did care to cock an ear, the walls of his flat on the edge of Edinburgh's Georgian New Town are hung so thick with paintings that it's hard to imagine much sound coming through beyond the faint thrum of the Leith Walk traffic three floors below.

And what paintings they are. Many are in the familiar hand of the late John Bellany, Moffat's great friend and his contemporary at Edinburgh College of Art in the early 1960s. Elsewhere there's a brooding landscape by Helen Flockhart – “the only pure landscape she ever painted”, Moffat says proudly. “They're usually populated by figures” – and facing the door as you enter the large, airy room is a massive painting by Steven Campbell, whose death in 2007 aged 54 robbed Scottish art of one of its greatest talents.

In his three decades teaching painting at Glasgow School of Art (GSA), Fife-born Moffat taught both those artists, as well as many other stellar names of modern Scottish painting. Among them are Alison Watt and Gwen Hardie, as well as the quartet of male painters who, along with Campbell himself, made up the so-called New Glasgow Boys: Ken Currie, Peter Howson, Adrian Wiszniewski and Stephen Conroy.

Moffat is still close to Wiszniewski and Currie and is currently working on a project with another GSA painting graduate, Karen Strang. “It has been part of my life to be in touch with them, see what they're doing, still retain a kind of friendship,” he says. “Of course you're not really friends when you're teaching them. It's a tutor-student relationship at that stage. But then it grows and develops – in unexpected ways sometimes.”

For a flavour of the esteem in which Moffat is held by his former pupils, I contact Peter Howson and ask him for his thoughts. “Sandy became my tutor in 1979 during my third year at art school,” he tells me. “Within a few months he had convinced me that art was not just a career, it was something you could live and breathe. A door opened to a new dimension for me. He introduced me to German Expressionism, classical music, opera and drama. We had numerous in-depth discussions and he was a source of complete encouragement that made me focus on the 'big ideas' in art. He was, and still, is my master and friend.” It's quite a testimonial.

So glance around the room at the works by Campbell, Bellany and the others, think about the figures they show and the mysteries, allegories and human dramas they represent, and you can see why Moffat scoffs at the idea that figurative painting is a dying form. There is a power here that's hard to put over in words.

“At the end of the day, portraits remind us that we're all human,” he says simply. “We all have eyes and noses and the same kinds of bits and pieces. And even when people are looking at a portrait that was done 500 years ago, the humanity of the whole thing is reassuring. And not just interesting but deeply interesting … Some people think that when we're looking at portrait in a sense we're kind of looking at ourselves and we're being reminded, via the portrait, of who we are and what we do and what we think about. So portraits have a tremendous resonance.”

Another former student Moffat still talks to is Turner Prize-winner Douglas Gordon, to his mind “a great artist … he reaches out to an audience and he has powerful things to say”. Gordon studied Environmental Art at GSA rather than painting and is best known as a film-maker and conceptual artist, but even he is coming round to the power of the portrait, says Moffat. “The last time I spoke to him, which was a few months ago, he said he was going to be dealing with portraits. So he's not a man who ignores the past. He's aware of what's gone before and he deals with that.”

Harder to spot in Moffat's room is another framed portrait, this one very different in nature from the paintings, though much easier to decode. It's a small photograph of Moffat and his son, green and white Hibs scarves around their necks, beaming into the camera as they celebrate the Edinburgh's club's historic 2016 Scottish Cup win. Despite loyalties which lie on the other side of the capital's footballing divide, I can't help smiling.

“We've had a terrible five-year period where everything went to the dogs completely, and now we've won the cup, which was incredible,” Moffat laughs when I mention the picture. “We've gone from a miserable, hardcore of seven or eight thousand to twenty thousand.”

We're talking ahead of a Scottish cup tie which will pit Hibs against Hearts for the third year in a row. Is he going to the game? “I'll wait until it gets a little bit warmer,” he laughs. Just as well. Hibs lose the tie.

But we're here to talk about art, not football, and right now there's plenty of it where Sandy Moffat is concerned. As well as being the subject of concurrent exhibitions at Edinburgh's Open Eye Gallery and the Lillie Art Gallery in Milngavie, this month sees the publication of Facing The Nation, a book about Moffat by critic, curator and art teacher Bill Hare. The artist himself turns 75 in March, so it's the perfect time to take stock of both life and career.

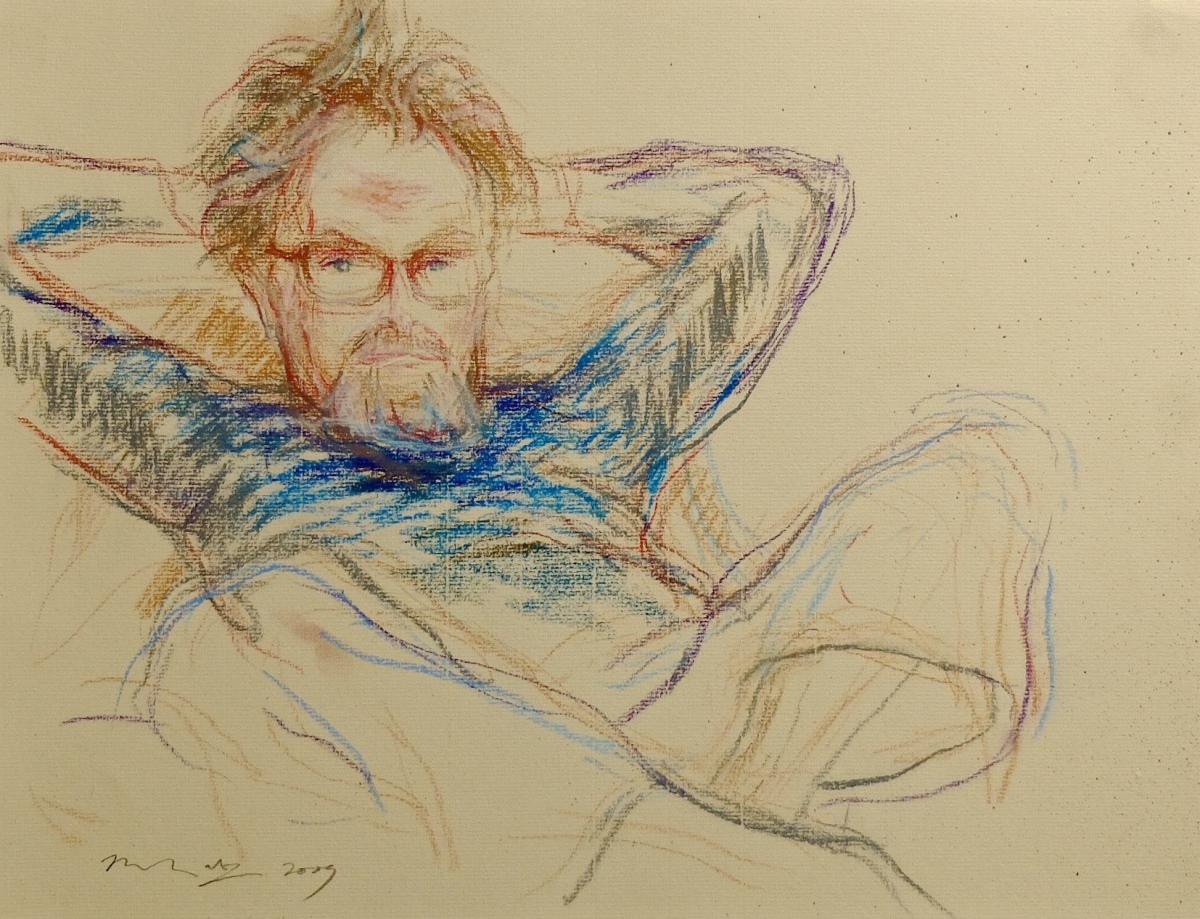

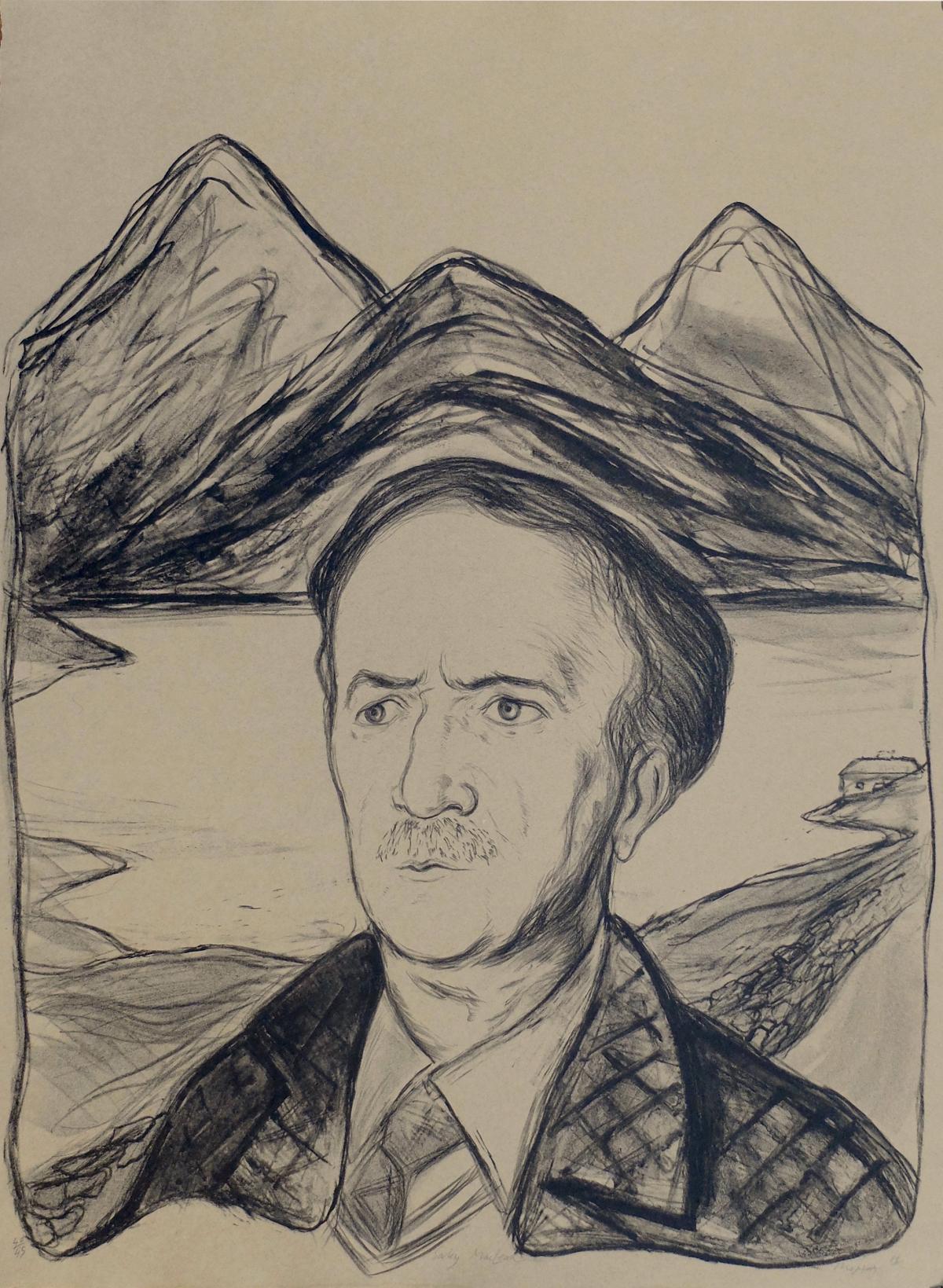

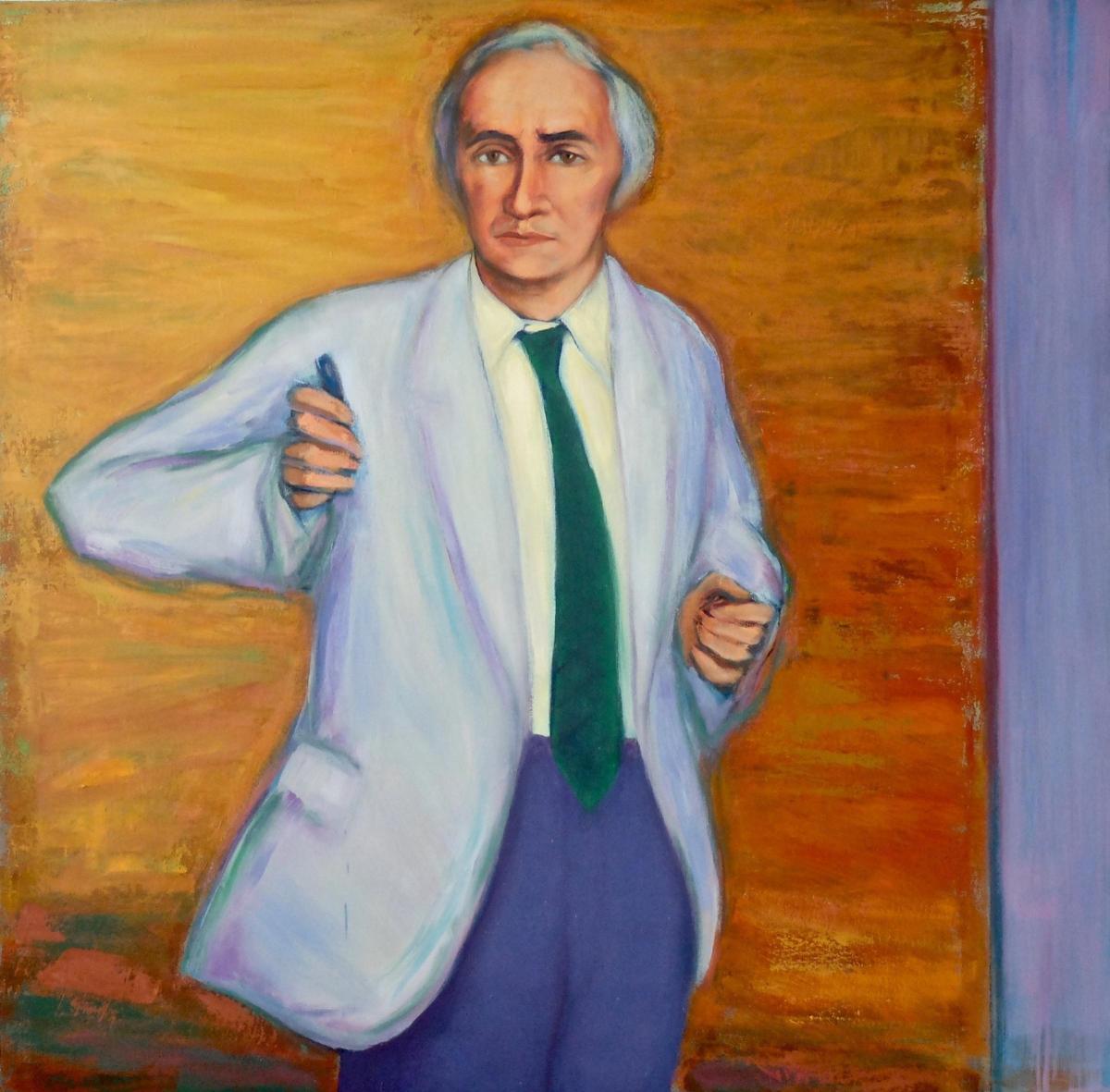

Structured around a long Q&A between Hare and Moffat, Facing The Nation contains portraits and drawings of some of the artist's famous ex-pupils as well as his studies of Scottish cultural luminaries such as Richard Demarco, Hamish Henderson and Alasdair Gray. There are also paintings of many of the other, lesser-known figures to have come into his orbit over the course of his 50 year career.

And of course there are the poets. Moffat's most famous work is Poets' Pub, completed in 1982 and an imagining of a convivial gathering of Scotland's greatest 20th century poets gathered around the person of Hugh MacDiarmid, who died in 1978. It's currently on show in the Lillie Art Gallery exhibition.

But many of those featured in it, including MacDiarmid, were also painted individually by Moffat from the late 1960s onwards. Reading the names of those who sat for him – among them Sorley MacLean, Edwin Morgan, George Mackay Brown, Norman MacCaig and Robert Garioch – you realise he had regular one-to-one audiences with some of the most influential Scottish voices of the 20th century.

The point isn't lost on Moffat, either. He's well aware of the privilege he has enjoyed and the shape his own life has taken as a result.

“I remember when I first painted Norman MacCaig, I'd probably finished the painting after a couple of sittings because it really went well,” he recalls. “But I had to get him to keep coming back because he was giving me his life story. I didn't want to stop that.”

Archie Hind, author of The Dear Green Place, was another loquacious and well-liked subject. “He came with a little notebook and put it down beside him and said, 'I'll be writing, just get on with the painting'. And then he didn't stop talking.”

And of course there was Muriel Spark, who Moffat painted in 1984. She sat for him every other day for a fortnight, a rare luxury.

“It's always great to speak to these people and she had a fascinating story. And when they're sitting there in the chair they start to tell things that they might not normally, and I'm just painting away and listening and maybe giving them a little prompt every now and again.”

Moffat had painted Sorley MacLean against a Skye landscape and asked if Spark would like something similar. He was imagining, perhaps, an Edinburgh cityscape, or the hills of Tuscany, where Spark had lived since the early 1970s.

“I showed her the portraits of the poets where I had encompassed the places, the landscapes, like Skye with Sorley. I said, 'Would you like me to do something? Italy?'. 'No, no,' she said. 'I only want me'. So I had my clear instructions and I just got on with it.”

Moffat's finished work, now owned by the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, shows the author sitting in a chair which seems to float against a rich blue background. Spark has a bright red scarf round her shoulders. Her glasses are clutched in her hands. There's a look in her eye which is either faraway or steely, depending on your take. “I think she liked the painting,” Moffat says. “She wasn't one to not give an opinion.”

Neither, it seems, is Moffat. It's over a decade since he left his post as head of Painting and Printmaking at GSA, but his own gaze has stayed fixed on that establishment, as well as on the wider world of British art schools. He doesn't much like what he sees.

“There are still a few former colleagues struggling on and they all say to me, 'It was bad when you left, Sandy, but it's a thousand times worse now'. And that's what I hear all over the UK.”

One issue he has is with the quality of teaching. Painting, he thinks, is taught “very badly” because there aren't enough artists teaching it. “One of the things that has happened in art schools is that everyone is looking to become a manager with a fancy job title. So instead of having teachers, you have course leaders, deputy course leaders, deans, all sorts of characters that didn't exist 50 years ago. Everything was so much simpler. And art school shouldn't be a complicated place. I remember my great friend Peter de Francia who ran the Royal College of Art said all you need is a tree, a notepad and a pencil.”

The tree, by the way, is to sit under when it rains, not to draw.

Another complaint is the profit imperative, which means attracting wealthy, fee-paying students, and the “managerial class” now running art schools who see “boosterism” and “slogans” as the way to do it. The result, Moffat thinks, is that art students end up viewing a four-year degree as the be all and end all, and leave art school with a false impression of their own worth.

“Now, because all these students are paying loads of money, they're told that once you have a degree, you're an artist. It's a piece of cake. Nobody fails,” he says. As a consequence, painting suffers. “There's a lot of craft involved in painting, and you need to do these things day after day after day if you're going to become a good painter, and that's no longer required.”

More concerning for Moffat, however, is the longer-term effect of this internationalised, market-based approach.

“My worry is what effect it will have on our culture, specifically here in Scotland when we have only a tiny number of Scottish students studying in our art schools,” he says. “Scottish students have been sacrificed because they don't pay fees. Anyone who can write the cheque and pay the fee is in.

“When I think of the time I began teaching in Glasgow, 99 per cent of the students were Glaswegian and they produced some incredible geniuses. And if you think of when Macintosh was a student, 100 per cent of the students would be Glaswegian and again they produced some wonderful creative people who completely transformed Scottish art and culture. This is what we should be talking about and thinking about.”

But hasn't GSA attracted a generation of talented international students, many of whom have stayed in the city and helped make it a powerhouse of contemporary visual art?

“Yes, but I think that's happening less now. I think that has possibly peaked. But I think that could be managed better as well. Of course it's wonderful to have students coming from all over the world, but not to the detriment of educating your own people. There has to be a balance.”

And that balance matters, he thinks, because art in Scotland contributes to something big: our understanding of who and what we are. The title of Hare's book is Facing The Nation, which refers to Moffat's career-long personal interaction with Scotland's cultural heavyweights. But perhaps it can also be read as the nation facing up to itself, seeing in those people's words and ideas a distillation of Scotland's essence which will in turn point a way forward.

To Moffat's mind, that way forward is full independence. “I've always been pro-independence, ever since meeting Hugh MacDiarmid in 1962,” he says. “It seems absurd that we're not. I think independence would bring a far greater focus from everyone on who we are, what we are, what Scotland is. There could be no shilly-shallying. We'd have to make decisions.”

And we'd also, I'm sure, have to continue to paint.

Facing The Nation: The Portraiture Of Alexander Moffat by Bill Hare is out now (Luath Press Ltd., £25); Poets, Portraits And Landscapes Of Modern Scotland is at the Lillie Art Gallery, Milngavie until February 8; Alexander Moffat: A View Of The Nation is at the Open Eye Gallery, Edinburgh until tomorrow.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel