As artist’s residencies go it’s a little out of the usual. A sailing boat, plying the waters of the Outer Hebrides, searching out the remoter spots, the places where the roads don’t reach. A retreat from the urban or “civilized” world, yet an immersion – hopefully not too literally - in the natural world. Unless the mere thought of bobbing about on the waves brings on such severe seasickness that you automatically reach out for the nearest solid surface, it’s hard not to see the appeal.

Certainly it was such for the six artists who responded to the call from An Lanntair, Stornoway’s arts centre, and Sail Britain, whose Coastline project has aimed to circumnavigate Britain, bringing artists, writers, scientists and musicians, amongst others, closer to the traditions and natural habitats of our varied coastline.

The exhibition Muir is Tir: Land and Sea, is the result of this unique residency, organized by Jon Macleod at An Lanntair, which has run over the past two years – a week on board the boat and a subsequent week in a shared bunkhouse on South Uist. The artists involved came from all over Scotland and further afield - Mollie Goldstrom, William Arnold, Amy Leigh Bird, Kirsty Dixon, Claire Macleod, Joanne Kaar and Helen Snell – and will exhibit alongside artists involved in the An Suileachan residency on Lewis’ Bhaltos peninsula.

Kirsty Dixon, born in Manchester and now based in London, was the only artist with any sailing experience on the 2017 trip, she tells me by phone from her “day job” in London working as an artist’s assistant in a big sculptural studio. “I’d done a bit of sailing about 20 years previously, and it was a chance to get back on the water. I like the sound of waves!”

The group spent the week in the Minch, learning to sail, living with no electricity, limited space and the wide open sea around them. “It is an extreme change from normal life, particularly if you are used to doing everything for yourself,” says Dixon, who tells me that some of her fellow artists were really frightened at times, both of the boat when it set at a 45 degree angle – quite normal, when you know to expect it, she says – and of the eminently changeable August weather, ranging from sunlit calm to gale force 7 in a matter of minutes. “Being on the water, it’s so powerful, you really appreciate the scale of it, the intensity. Everyone really felt they’d had a real experience, like they’d stepped into secret places,” she says. “A few people were seasick too,” she adds, with a laugh.

They rubbed along very well, she says, spending the evenings together cooking, chatting, planning. “It feels quite isolated and disconnected from the world, but you are so connected to the people in the small space around you. You can’t get away from each other, you are having to work together to coordinate the sailing of the boat, to move around. You have to work as a team to even get a cup of tea around the table!”

I ask Dixon if she came to the trip knowing what she wanted to get out of it, or if she simply blew (quite literally) with the wind. Both, she says. “Luckily the skipper, Oliver Beardon, was very relaxed about itineraries.”

“Artists are very, oh what’s that over there, and then two hours later, everyone’s wondering where you’ve got to…Oh, I was just looking at that thing.” Infuriating, she says, but Beardon didn’t seem to mind at all.

Fellow artists included a composer, Verity Standen, whose ability to get them all singing working songs was “a fantastic thing,” says Dixon, who tells me Standen was very interested in the Hebridean song culture and history. Standen is unable to exhibit at An Lanntair but other participants showing include William Arnold, a photographer who developed a fascination with seaweed.

“We all did, really,” Dixon says, “the colour, the texture, the variety, the connection to the land and the sea, the fact that the seaweed is everywhere!” They collected it, photographed it, ate it, often foraging to supplement their dinners. Arnold photographed them extensively, taking seaweed samples which he then exposed directly to light creating stunning translucent images without a camera which will be on display in the exhibition.

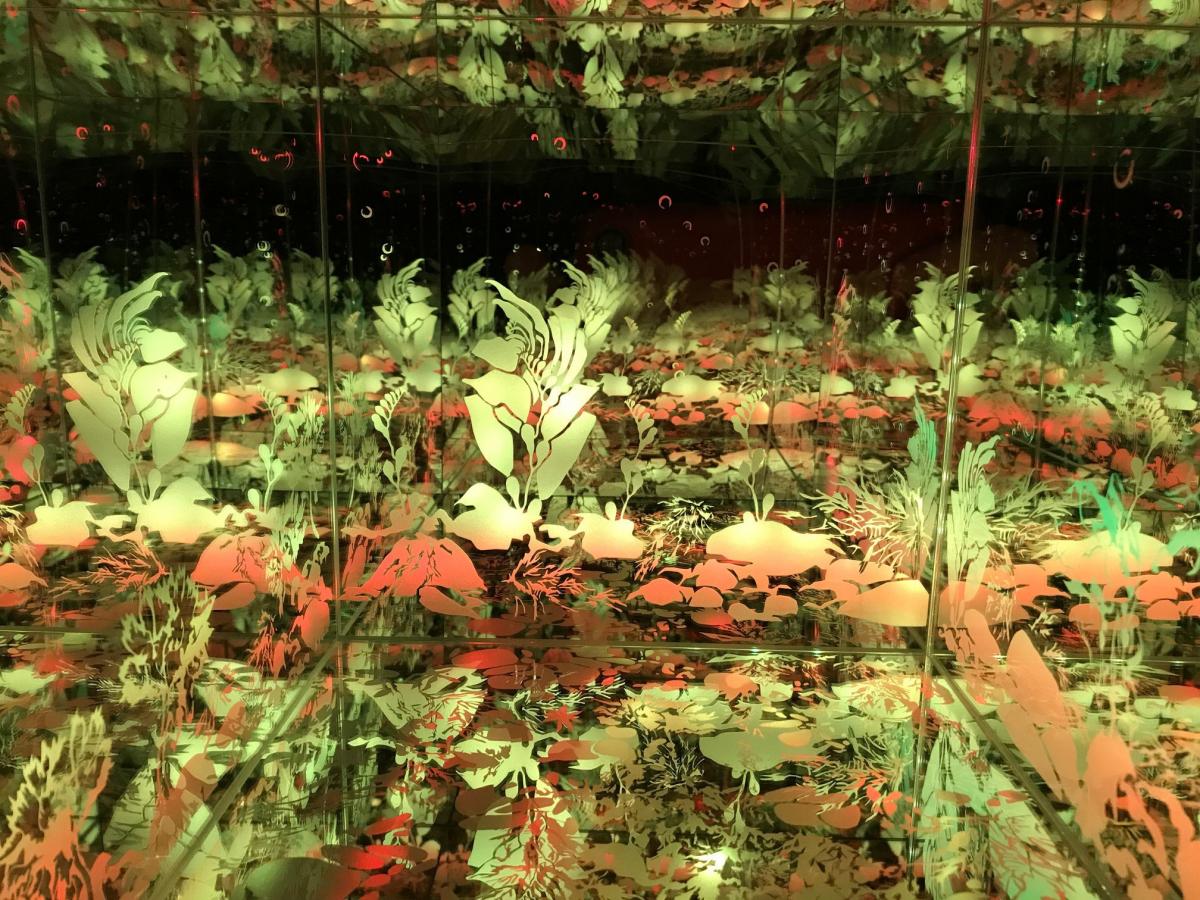

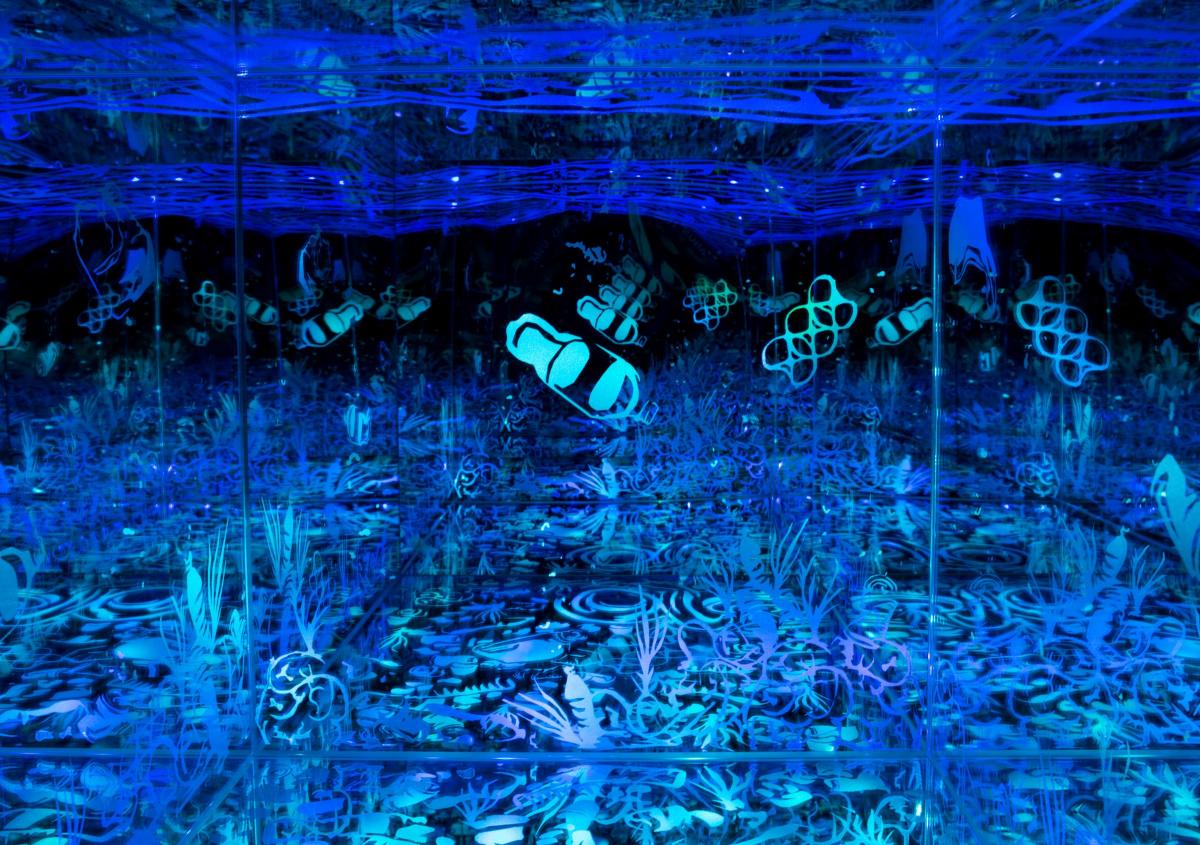

Other artists who have spent the past year working on material from their residency in their home studios include Mollie Goldstrom, a printmaker from New York who has a longstanding fascination with seaweed, more usually to be found picking up seaweed on the East coast of America. Dixon’s own work is in light, using “infinity mirror boxes” or creating larger light installations. The An Lanntair space has a triple height ceiling, Dixon says, so she is bringing this larger work to Stornoway. It’s a 24 hour trip on the overnight train and ferry from London. “Like stepping out of one world into another.”

Muir is Tir: Work from An Lanntair residencies, An Lanntair, Kenneth Street, Stornoway, Isle of Lewis, 01851 708 480 lanntair.com Until 6 Oct, Mon - Sat, 10am – 9.30pm

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here