WITH its silver sand beaches, high sea cliffs and big, portentous skies, the Isle of Islay (Ìle in Gaelic) is well named the Queen of the Hebrides. The southernmost of the Hebrides, it enjoys a comparatively mild climate and combines fertile agricultural land with rugged quartzite hill country, woodlands and heath. It is the flitting westerly light, though, that makes Islay bewitching rather than simply beautiful.

A summer dawn can turn Loch Indaal – the sea loch that, with Loch Gruinart, almost bisects the island and probably once did – into a tongue of molten bronze.

Looming winter storms bathe the lochside village of Port Charlotte in a lavender glow. The fishing village of Portnahaven is lit in flecks of copper and gold as the sun slips behind the mighty Atlantic. This is a place where the view, often enhanced by the three majestic quartzite mounds of the Paps on the neighbouring Isle of Jura – which is connected to Islay by a regular ferry service – is never the same twice.

Under shifting skies, the sea can change from duck egg blue to tarnished silver to jade in a matter of moments. The sea may boil at times and fierce winds lash Islay’s 130 miles of coastline, but overall it is a place of abundance. In spring, the fertile coastal machair erupts in a carpet of wild flowers, with wild orchids, bird’sfoot trefoil, clover and sea pinks fringing the island’s magnificent beaches in rich yellows, pinks and blues.

Freshwater lochans teem with trout, while the island’s 20 or so commercial fishing boats land lobster and crab. There is no better place to sample local venison, lamb or beef, and few Scottish islands with as many cosy hostelries in which to do so.

Its varied terrain means Islay is home to a cornucopia of wildlife. At certain times of year it’s hard to avoid leaping roe deer and boxing hares up by Loch Gruinart, and the island also supports populations of red and fallow deer, wild goats, shrews, including a distinct island species, rabbits, voles and stoats. Seals and otters frequent the many rocky bays and skerries, and whales, porpoises and dolphins are sometimes seen close inshore.

However, it is for its birdlife that Islay is justifiably famous. Some 200 species visit the island, and nearly 100 species breed there. Visiting twitchers have every chance of spotting raptors, such as golden eagles, merlins, peregrines, kestrels, sparrowhawks, hen harriers, and barn, tawny and short-eared owls – or more rarely white-tailed eagles. The rare chough can be seen in remoter areas, such as Ardnave point, and the lapwing, curlew and corncrake frequent the island’s farmlands and the RSPB reserve at Loch Gruinart. The reserve is also home to wading birds, such as oyster catchers, godwits, redshanks, snipes and sanderlings, and coastal areas support sea birds, including gulls, fulmars, gannets and guillemots.

The jewel in the crown is the island’s geese. The approach of winter brings some 50,000 migrating white-fronted and barnacle geese from Greenland and Canada to Islay. From October to April, huge numbers of these birds can be seen roosting at Loch Gruinart and in the fields around Bridgend or swooshing through the air in formation. In winter, Islay is home to an astonishing 70 per cent of the world’s Greenland barnacle geese and 40 per cent of its Greenland white fronted geese.

It is customary to refer to Islay – and the other Hebridean islands – as remote or wild. Nothing could be further from the truth, and this designation represents a profound failure of the modern metropolitan imagination. Islay is but 40 km from Glasgow as the crow flies and closer still to the Irish coast. On a clear day, you can see the Antrim hills from the Mull of Oa, Laphroaig bay and Pornahaven on the tip of the Rhinns, the island’s southwestern peninsula.

Only when General Wade built his military roads in the 18th century to subdue the Highlanders did the sea come to be seen as a barrier. For thousands of years prior to that it was the natural highway, connecting Scotland’s coast and islands, and Islay was at its centre, attracting traders, missionaries and invaders. The many memorials to shipwrecks around Islay’s coast are testimony to the island’s central position – as well as a reminder that this highway was more treacherous even than the A9 trunk road between Perth and Inverness.

The island has a long history of human occupation and was at one time the epicentre of the Lordship of the Isles, a vast maritime empire independent of the Scottish crown. The landscape is everywhere pitted with human history, from Iron Age forts to the ruins of more recent settlements cleared in the 1800s. Today’s population is a quarter of the pre-Clearance peak of 15,000 in the 1830s.

The 18th century saw the building of the first whisky distillery on Islay: Bowmore, established in 1779. Croft stills had long been part of the landscape, going underground when the Scottish parliament introduced taxes on malt at the end of the 17th century and burrowing further underground when taxes were increased after the 1707 Acts of Union.

By the time Walter Frederick Campbell became laird in 1816, Islay's population had grown exponentially, and three further distilleries had been established in the Kildalton bays of Ardbeg, Laphroaig and Lagavulin on land leased from the laird. Walter Frederick built the villages of Port Ellen, Port Charlotte and Port Wemyss, but by 1848 he was bankrupt. The Islay estates were split up and sold off to private individuals, and much of the island remains in the ownership of a few individuals today.

Of the new landowners, the most notable were the Ramsays, owners of the Kildalton estate. John Ramsay acquired the

now defunct and much lamented Port Ellen distillery in 1840, having first managed it on behalf of Walter Frederick Campbell. When the laird’s finances hit the skids, Ramsay purchased the Kildalton estate, later expanding into the Oa and much of the present day Laggan estate. An MP for Stirling Burghs and a Justice of the Peace, Ramsay co-founded a cargo service between Glasgow and Islay and helped to promote the sale of Scotch whisky in the USA.

What John Ramsay had built up, his son, Iain Ramsay, who inherited the Kildalton estate when his mother died in 1905, contrived to dissipate. Having survived the First World War, Ramsay junior was forced to sell the Kildalton estate in 1922. The purchaser was a wealthy and eccentric English landowner and traveller called Talbot Clifton, but the days when ordinary Ileachs were obliged to care were drawing to a close – at least if you worked in the whisky industry. Each of the Kildalton bays’ distilleries was purchased by its existing tenant. A new era was beginning. The path of modernity was

engaged.

Today, Islay has a permanent population of 3,228 (2011 census), engaged mainly in fishing, agriculture, tourism and whisky distilling, and it attracts tens of thousands of visitors each year. They come for the scenery, the sport (golf, surfing, horse riding and fishing), the craic – and, of course, the world-famous single malt whiskies.

The island supports 10 festivals, including a jazz festival, a book festival and the Islay sessions, a traditional music festival. Fèis Ìle, a festival of music, malt and the Gaelic language that takes place each year in the last week of May, marked its 16th anniversary in 2016. The special bottlings produced by the distilleries for Fèis Ìle have become an event in themselves.

Islay is also a centre for the regeneration of the Gaelic language. Ionad Chaluim Chille Ìle (the Columba Centre Islay), which co-operates with Sabhal Mòr Ostaig, the Gaelic college on the Isle of Skye, supports Gaelic language and culture, as well as linguistic and cultural links with nearby Ireland.

Now, as in the past, the surrounding sea creates both problems and opportunities. Few are those who have never had reason to complain about the ferry service to the mainland. At the same time, lying on the seabed not far from the ferry terminal at Port Askaig is one of the most advanced tidal power projects in the world.

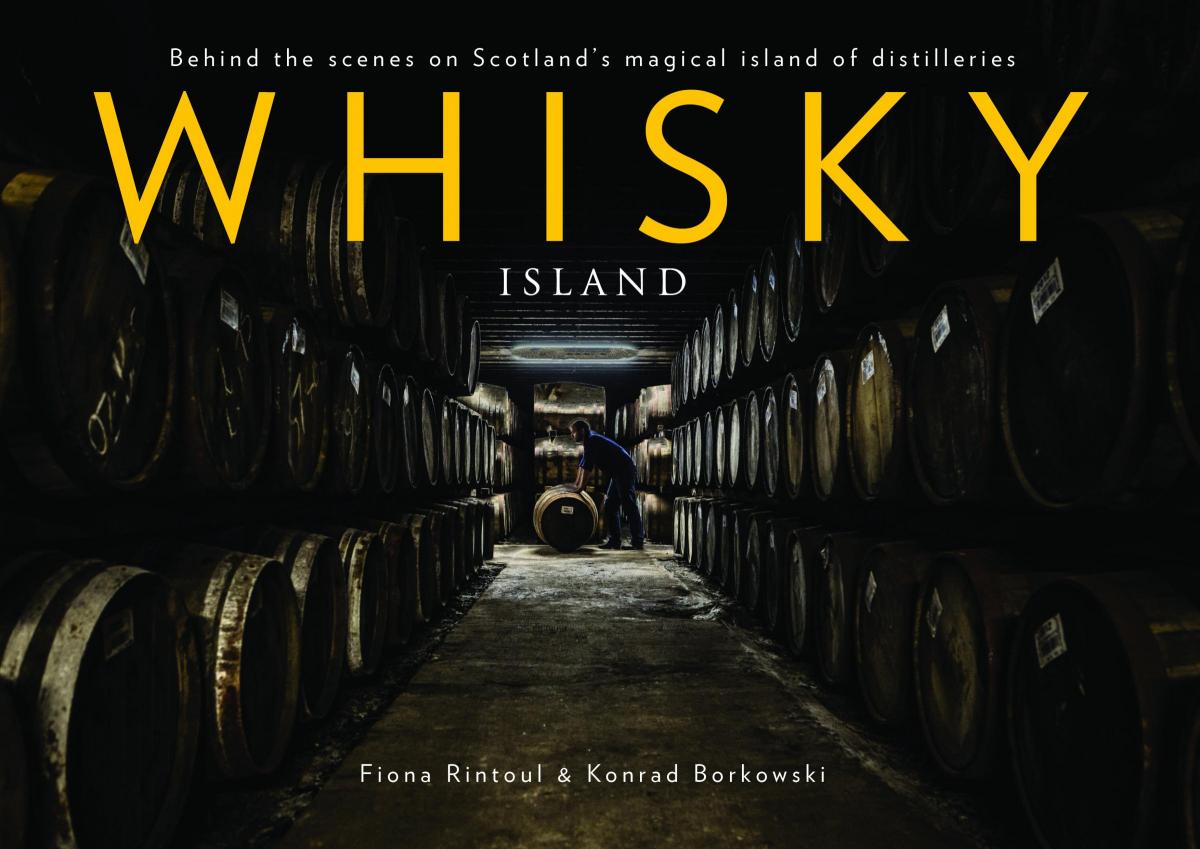

Part of it all are the island’s eight whisky distilleries, these days producing some of the finest single malt whisky on the globe. The whisky industry’s fortunes have ebbed and flowed down the decades, and Islay’s fortunes have sometimes moved with them, but it is the island that stamps the whisky, not the other way round.

Whisky does not define Islay, but Islay does define its whiskies. Redolent of the surrounding peat, kelp and sea air, these fine spirits are as independent and robust as the Ileachs who make them.

This is an edited extract from Whisky Island by Fiona Rintoul and Konrad Borkowski, published by Freight Books, £20

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here