TAKE the B7040 near Elvanfoot on an autumn day, follow it up through hills of burnished ochre and across tributaries flowing to the Clyde, and you arrive in Leadhills, the second highest village in Scotland. Once upon a time, this landscape was industrial, pock-marked by mine shafts and a lead smelting plant, its noxious fumes carried on the prevailing wind.

Today, though, it is eerily quiet; its population shrunk to just over 300, its church locked up, its bakeries, butcher and tailors gone. The only testaments to its heritage are the grey scars on the slopes, the tidy rows of slate-roofed cottages, the curfew bell, which rang to signal the change in shifts, and the miners' library.

It is the last of these I have come to see. Housed in a converted cottage, with a narrow gabled porch and gridded windows, it has no aura of of historical import. But as the first subscription library in the UK, it established a tradition of working-class learning that was to become as deeply embedded as the tonnes of galena ore that still lie beneath a landscape known as God's Treasure House.

Within a few decades of the library's founding, the belief that everyone should have access to books had made its way down from the Lowther Hills. Similar ventures started springing up in rural outposts and industrial heartlands across the UK. By the 1850s, it was such an established tenet, an Act was passed to give local authorities the power to set up public libraries, though, ultimately, it was Andrew Carnegie's money that brought many of them into being.

Inside the Leadhills library, which now serves as a museum, the weathered tomes the miners once pored over sit alongside a display of of minerals – chalcopyrite, susannite and leadhillite – which sparkle and shine. The religious and political tracts, the guides to far-flung corners of the globe, the first editions of novels by Sir Walter Scott and Anthony Trollope were also gems lending lustre to lives of toil. The phrase "learning makes the genius bright" is emblazoned on an old pulpit, from which the president would address the monthly meetings. The line is taken from a verse by Leadhills-born poet Allan Ramsay, after whom the library was originally named. "As the rough di'mond from the mine/ In breakings only shows its light/ 'Till polishing has made it shine/ Thus learning makes the genius bright," he wrote in his pastoral play The Gentle Shepherd.

Later this month, the library, founded in 1741, will celebrate its 275th anniversary; villagers will meet in its single musty room to look at the newly-restored banner, the oldest in the country, and hear about the latest efforts to preserve and, perhaps, digitise the collection. But those who are closest to it – its trustees and committee members – are conscious of an irony: as they work to raise awareness of its significance, the tradition of learning it pioneered is threatened.

Though the Scottish Government sees libraries as a priority, and has awarded £2.3 million in funding since it launched its libraries strategy last year, cuts in local authority budgets mean services are under pressure. The situation is worse in England; but, even here, 25 libraries have shut since 2010, with more closures planned. Staffing levels and opening hours have also been reduced.

"Libraries have always been about social health and wellbeing," says Pamela Tulloch, chief executive of the Scottish Library and Information Council (SLIC). "Back then, it was about education and self-improvement which in turn improved people's life chances.

"Now, it's about being able to engage in the 21st century, but the raison d'etre hasn't changed. Libraries are an asset to the community, and in deprived and rural communities they can be a lifeline."

Leadhills library was certainly a boon for the miners whose lives consisted of working long hours and going to church (although a disproportionately large number of hostelries also offered a less spiritual distraction from the subterranean blues).

But then, in 1734, James Stirling of Garden was appointed manager of the Scots Mining Company, which ran the Leadhills pits, and everything changed. Stirling was a brilliant mathematician. In another era, he would have been an academic, known only for his formulae and permutations. But he was also a Jacobite so no university would employ him. After spending time in Venice – from which he was forced to flee after uncovering the trade secrets of the glassblowers – he ended up revolutionising working practices.

Though he had no background in the industry, he instinctively understood healthier miners would mean more productive miners, so – more than 60 years before Robert Owen introduced his reforms at New Lanark – he cut the working day, turfed out the ale-sellers, set up a school, brought in a doctor and introduced a primitive health insurance scheme. He even persuaded the Earl of Hopetoun, who owned the land, to give each miner a small plot on which to grow vegetables.

Moving in Enlightenment circles, Stirling would have encountered John Locke's theory of mutual improvement – the idea that people learn better as a group – and the work of US Founding Father Benjamin Franklin who first linked it to reading and libraries. In all probability, then, it was Stirling who first mooted the idea of a subscription library – a library funded by its members. But he did not found it himself; nor, despite earlier theories, did it begin with an act of philanthropy on the part of either the Scots Mining Company or the local gentry. It was set up and run by the miners themselves.

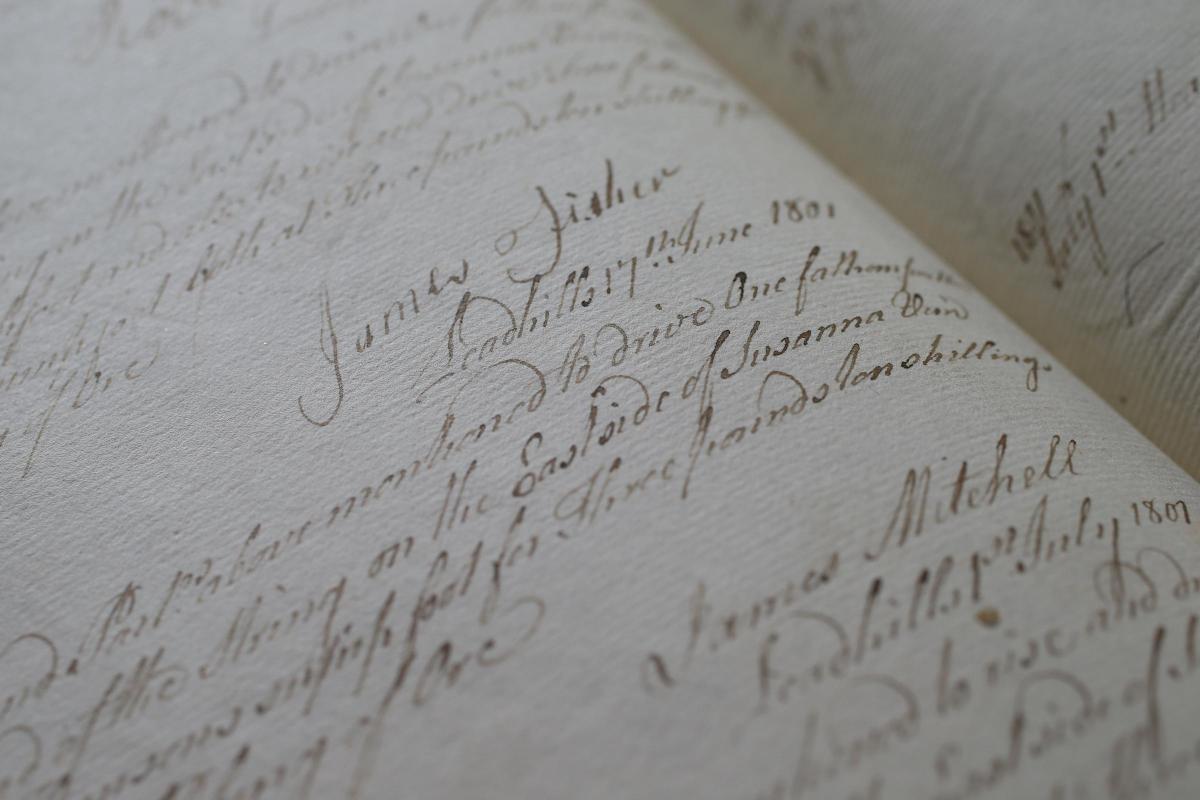

This fact was recently established by academic and Liberal Democrat politician, the Rev Dr Margaret Joachim who, as part of an MA on the History of the Book, spent weeks cross-referencing the list of original library members with its collection of Bargain Books – historic journals which recorded the agreements struck between groups of workers and the overseers as to how much they were to be paid for extracting a specific quantity of lead. "Of the 23 names on that list, eight appear as miners at exactly the right time in the Bargain Books," Joachim says. "Three of the founding members were overseers, one was a senior clerk and one was the village surgeon, but most of the remaining 10 have family names which were common amongst Leadhill miners of the period.

"So the library was not born of paternalism, it was miners doing it for themselves. It was their money, they drew up the rules and they decided which books to buy."

Having a library must have been important to those involved; the first members paid around four shillings a year, no meagre investment when their annual income could be as little as £20. Right from the start, they bought a mix of books. Though, as might be expected, around 40 per cent were religious, 10 per cent were historical, 10 per cent travel guides and 10 per cent novels (and the rest a mix of other genres).

In the early days, membership was boosted by men from neighbouring Wanlockhead. Although less than two miles apart, the villages lie in different local authorities (South Lanarkshire and Dumfries and Galloway respectively) and there is a longstanding rivalry between them. Even now, Wanlockhead takes a pride in being 17 metres further above sea level than Leadhills, making it the highest village in Scotland.

With such intense competition, it isn't surprising Wanlockhead wanted its own library, which it set up in 1756. A third mining village, Westerkirk at Langholm, founded a subscription library in 1792. Word of these mini-athenaeums soon spread to the cities and the villages became objects of curiosity for the literati who ventured north to cast a condescending eye over the hoary-handed yet learned labourers. Author and poet Dorothy Wordworth was impressed by a Leadhills miner she met during a tour of Scotland. "He said they had got a book into [the library] a few weeks ago which had cost £30 and that they had all sorts of books. 'What, have you Shakespeare?' 'Yes, we have that'," she wrote in 1803.

In 1892, writer, social reformer and friend of Charles Dickens, Harriet Martineau seemed distressed by the workers' choice of reading material. "What a blessing it would be if some kind person would send them a good assortment," she wrote. "What a new world it would open up to them."

As dust specks eddy, committee chair Ken Ledger takes a tome from the library's listed bookshelves and opens it gingerly lest its pages should crumble in his hands. Ledger, a former police officer, has been involved with the collection since he retired to the village from Yorkshire, 15 years ago. Standing next to him is John Crawford, the chair of the Leadhills Heritage Trust and a library historian.

Together, they conjure up the ghosts of the miners, sitting impatiently on the long benches, gazing up at the book-lined walls. "It was all very formal," says Crawford. "They would assemble, then take their books up to the desk. There were six inspectors who checked to see if they had been damaged in any way. " Once they had been returned, the men would sit in order waiting for their turn to choose a new one. Each month, the order would change so everyone got a fair chance.

The Leadhills Miners' Library flourished for almost 200 years; in 1821, it had 1,500 books, and in 1904, 3,805. Membership peaked in 1822 at 107, with another spike during the First World War when productivity was high. But by 1939, the last mine had closed. As the population declined, from a high of 1,500 so did the membership.

In 1940, the Lanarkshire County Library took it over and ran it until 1965, when it was replaced by a mobile service. At that point, the building shut – with many of its books in situ – and it sat there like a grounded Marie Celeste until locals, including playwright Hector MacMillan, launched a campaign to save it. It reopened as a museum in 1972.

In a cottage opposite the now defunct Lowther Church lives 89-year-old Mary Hamilton, former committee chair. Born in the village in 1927, she remembers trying to keek through its windows when she was barely old enough to recite the alphabet. "Children weren't encouraged to go in back then," she says. "It was a place of mystery, so we used to go up and down past it. We didn't know what went on behind closed doors."

As time went on, Hamilton grew to love books, so her mother joined the library to ensure a steady supply. "It was historical novels I liked most," she says. "Especially ones by Annie S Swan. I loved The Flight of the Heron [by DK Boster] about Bonnie Prince Charlie when they were hunting him, and how he fled to Skye."

Hamilton is a walking almanac of Leadhills history: a redoubtable woman, who has positioned herself on the battlements of its past. The walls of her living room are decorated with line drawings of her house which she calls Flexholm as an act of defiance against the faceless bureaucrats who changed her address from that to the more anodyne Main Street. Mention New Lanark and her hackles rise at the way Robert Owen's fame has eclipsed James Stirling's.

Hamilton has been involved in running the library since the late 1970s. It comes as no suprise, then, to hear her talk about her role in seeing off an attempted coup by the National Libraries of Scotland. "There was a professor came here at one point – he wanted to take our books to Edinburgh," she says. "But the committee was all women then. There were 12 of us, and we weren't having it, so he fought a losing battle."

Today, Leadhills Miners' Library, staffed by volunteers, opens between 2pm and 4pm on Saturdays and Sundays, from May to September (at other times by appointment only). It contains works of great historical significance, including William Chetwood's The Voyage and Adventures of Captain Robert Boyle. But many of its books are in poor condition, and it is not as well-known as it ought to be. The trustees and the committee are working hard to rectify the situation: last year the building itself was renovated and its banner restored. Now they hope to carry out a conservation survey of the books and raise money to save those under greatest threat.

But libraries have always wormed their way deep into people's affections and communities have always campaigned to save them. Joachim tells a story of just how hard the Wanlockhead miners fought when a misguided decision to buy a set of encyclopedia threatened to sink theirs in 1803.

"The encyclopedia was being produced in parts and the members had been quoted a price for four parts a year," she says, "but the Napoloeonic wars caused enormous inflation and prices rose inexorably.

"Also, encyclopedia salesmen were already notorious in the 19th century and – though they had been told to expect four parts a year – there were times when they got sent 13 all at once. Yet, they were determined this wasn't going to wreck them. First, they imposed a levy of a shilling on every member, then they raised the annual subscription, until eventually – in 1817 – they reached a point at which they could honourably stop paying."

Thirty-seven miles from Leadhills, in neighbouring North Lanarkshire, lies a former coal mining village, Newarthill – once home to another man at the vanguard of working-class learning, Keir Hardie, who educated himself out of the pits to become the first leader of the Labour Party.

Earlier this year, the local authority listed Newarthill Library as one of four it planned to close to cut costs. But local people, including the writer Damian Barr, protested against the decision. Barr says the library saved his life. Growing up gay and bookish in the west of Scotland, it gave him sanctuary from the boys that spent the summer tormenting him.

Picture him pale and freckled, sitting cross-legged between the shelves, reading Stephen King novels, and escaping to a world beyond the bullies, just as the miners escaped to worlds beyond the mines. The Newarthill protest led the local authority to defer closure so the community council can form a group to take over the running of it, but some campaigners, including Barr, are seeking a judicial review to force North Lanarkshire Council to keep funding it.

"When we close libraries we shut doors to the future. We are saying to children: 'Stay where you are, go no further,'" Barr says.

That libraries are a route to better, more rounded lives is something the miners of Leadhills understood long ago.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here