THE Cairngorms, like much of our countryside, are closed due to Covid-19. We wannabe visitors are warned not to go there, nor even leave our homes for more than a local walk. The mountains, therefore, seem farther away than ever – as if lockdown has stretched, time and space, elongating roads and altering the whole configuration of our universe.

The last time I was in the Cairngorms was in February when the wind howled at 90 miles an hour, blizzarding the peaks, and making it impossible even to approach the high places. On only one day – a momentary bright, clear respite from storm Ciara – were the slopes of the majestic Cairngorm skiable. So we, a bunch of families, blocked in to our holiday let, sledged, wandered through trees, took dips in the freezing lochs and battled through snow flurries.

That time and place now seem a world away – crowded, social, huggy, open, free, elusive. But there are ways we can go to those wilds, even in these times of coronavirus lockdown. That’s why we have turned this Insider Guide to a stuck-insider guide to the ways, in our minds, we can still travel – through the transportings of books, music, films, art, poetry.

Root intelligence. How German forester Peter Wohlleben changed the way we see trees.

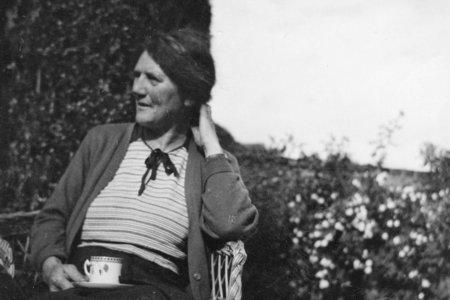

What to read There is no better place to start than a roam through the Cairngorms with Nan Shepherd’s masterpiece The Living Mountain – written during the 1940s but not published till 1977 – for it’s not just about place, but also about an attitude of mind, a slowness and engagement with the world, and a kind of aimlessness. Shepherd disdained the race to the top, and was more interested in the inner mountain, and what the landscape, fully experienced, and revisited again and again, can do our sense of ourselves. “Haste can do nothing with these hills,” she writes. “I knew when I had looked for a long time that I had hardly begun to see.”

Quotable highlights Among the book's pleasures are her descriptions of mountain streams: “Water so clear cannot be imagined, but must be seen. One must go back, again, to look at it, for in the interval the memory refuses to recreate its brightness. This is one of the reasons why the high plateau where these streams begin, the streams themselves, the whole wild enchantment, like a work of art is perpetually new when one returns to it.”

Why it’s relevant As we are forced, in this current crisis, to slow down, The Living Mountain offers more than just momentary escapism. Its gift is a state of mind to carry into our own smaller worls, a new way of looking out of our windows, or taking in the streets and wild patches of our local area. It's about a localism and closeness of experience. “It is a tale too slow for the impatience of our age – not of immediate enough import for its desperate problems,” Shepherd writes at one point. “Yet it has its own rare value. It, for one thing, a corrective of glib assessment. One never quite knows the mountain, nor oneself in relation to it.”

At times it can feel as if we are now trapped in a lockdown too slow for the impatience of our age – and it may help for us to see our local existences through her eyes. Whilst restricted by lockdown, we may not see a ptarmigan appear, as she does, rising with white wings from among grey stones, but we can watch a blackbird calling from a rooftop at twilight. We can observe a tree from a window and count the blossoms as they unfurl. We can wake early and catch the dawn chorus. This kind of thing, is there for most of us, even in a densely-populated city – a reminder that one never quite knows the place one lives in, nor entirely oneself in relation to it.

Who to follow @RobGMacfarlane. When the acclaimed nature writer Robert Macfarlane started his social media #CoReadingVirus Global Book Group, with a group reading of The Living Mountain, thousands joined – and no wonder. Macfarlane has done more than arguably anyone to help foster the recent cult of Nan Shepherd, creating radio shows, documentaries and writings around it. "I read it, and was changed," he wrote in the afterwords to the current Canongate edition. Here, on his twitter threads, there is a community that offers more than appreciation of Shepherd’s words – there are also photographs, paintings and rich testimonies to the wonders of this area of the Highlands. There is also solidarity with others whose connections to the wild places have now been stretched.

Robert Macfarlane spells out the ABC of landscape

What to watch If what you want is to go full slow, then there is no film more and hypnotic than Ben Rivers’ Two Years At Sea – an example of what's been called "slow cinema". In murky 16mm black-and-white, it follows Jake Williams, a hermit living in a tumbledown house in the Clashindarroch forest – outwith the Cairngorm Park, but evocative of the area ¬ as he goes about his daily chores, takes a long lie in the heather, has a shower, sorts through his bric-a-brac. Or, if you find that’s taking you into too much of an existential stupor, there are more pacy options. Rewatch this year’s Winterwatch from the Dell of Abernethy or go Cairngorms-spotting in Mary Queen of Scots, Outlander and The Outlaw King.

What to listen to There are few albums that conjure up the Cairngorms landscape quite as intensely as Hamish Napier’s The Woods – with its contemporary arrangements of traditional dance tune forms, eerie sounds, and interwoven field recordings of axes chopping wood, the call of woodland stags and ice clinking in a loch. It takes you, not so much to the area’s high places, but to its lower reaches, the trees and forests that are also part of its grandeur. Napier, who grew up in Strathspey, began his composition by taking a walk with a tree book. “What I viewed as simply ‘the woods’,” he realised, “is now a gathering of recently acquainted characters, e.g. alder, willow, hawthorn. We are tree creatures. After the last ice age 100 centuries ago, the forests expanded across the barren landscape and with it the human population. Woods and man evolved together. Let us regain the forests and our common knowledge of them.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article