Joseph Farrell

It is never comfortable to be described as central anywhere, the space in between two more significant places, even if the twin poles in the case of Central California have the mystique and allure of San Francisco and Los Angeles. The region glories, at least for the most part, in the description given it, and with good reason.

Travelling in the area by car, and there is little public transport, is itself a chapter in that quintessentially Californian romance of the open road. Hollywood, which lies at the end of the trail, has imprinted on the western imagination scenes of gilded young couples in a convertible, she with golden hair flying in the breeze and he driving with too little concentration through spectacular scenery. Highway1 snakes and twists along the coastline from away up north beyond San Francisco down firstly to Carmel and Monterey, where the redwood forests and the seascapes become even more breath-taking, and then on through wine-growing country to San Simeon where William Randolph Hearst built his fairy-tale ranch packed with works of European art eccentrically displayed, and even south of LA before it runs out of stamina at San Juan Capistrano.

This was once Mexico and the route is dotted with towns with Spanish names – Santa Cruz, San José, Avila Beach, San Luis Obispo – many of them famed in song and story. I managed to get lost on the way to San José, but that is what the song requires. I fetched up in Santa Cruz, with its lovely ‘replica’ of the original Mission church, which may not be the first port of call for today’s hedonist visitors, but which is worth a visit, at least in intervals between enjoying the town's more obvious attractions – sun-bathing, surfing, strolling along the famous Beach Boardwalk featured in many films, or lounging on the Municipal Wharf which stretches out into the enchanting Monterey Bay.

The publicists, whose brochures are lavishly illustrated and given way in abundance, are now keen to emphasise the Mexican heritage. If the Missions were designed as religious establishments, and some remain at least partially so, they are fully incorporated into the tourist business and supported by public and private sponsors to demonstrate the history of an area which is chronically afraid of not having any. There was originally a line of 21 Missions marking the route taken by the missionaries from Mexico as they made their way north into modern California to convert the Indians and secure the lands for the Spanish Crown. The leader was Fra Junipero Serra, a Franciscan explorer-priest who is buried in the Mission in Carmel, canonised by Pope John Paul 11 and given a place of honour in Washington among the founders or discoverers of the various American states.

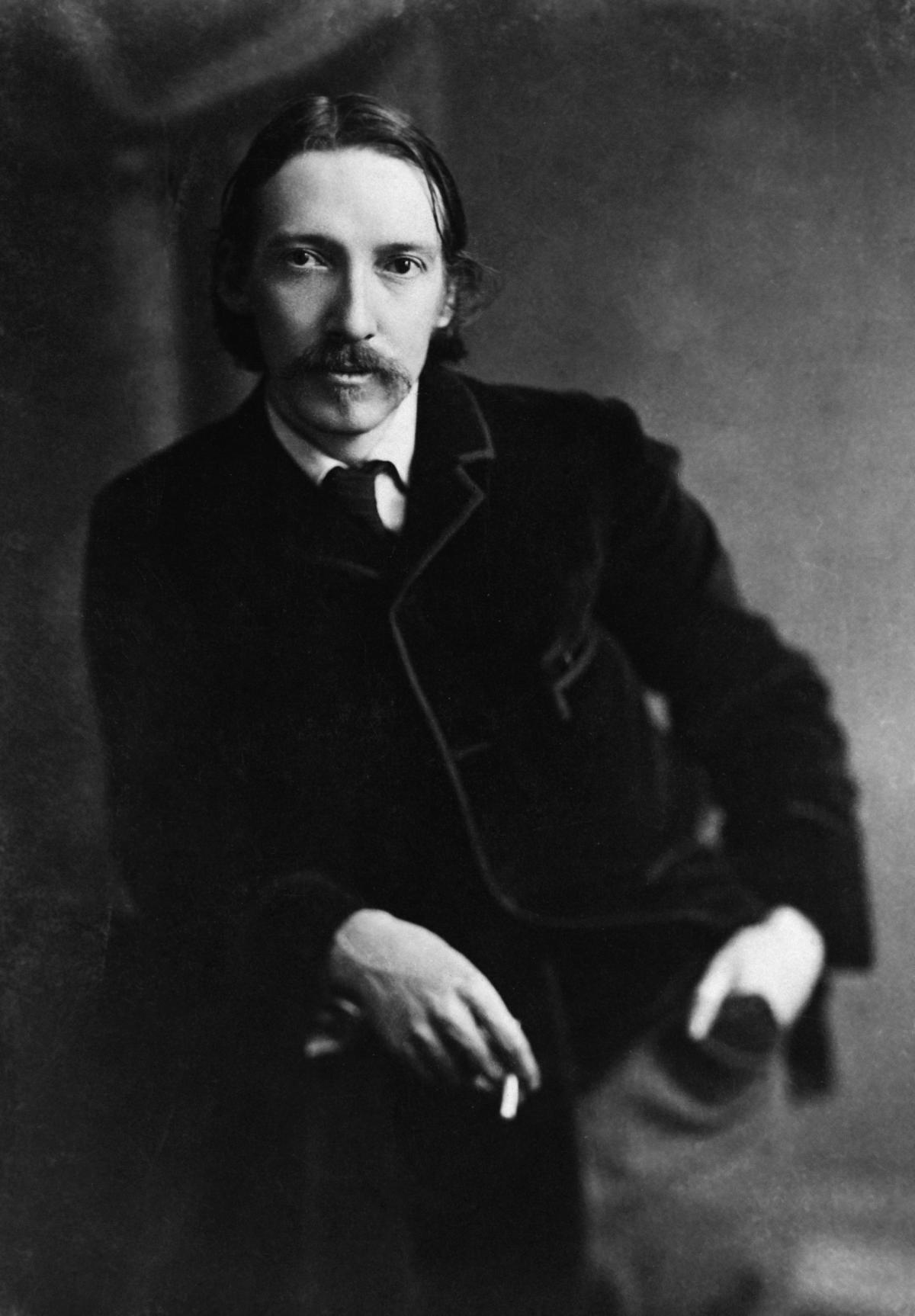

One of the people who was most appalled by the later neglect and disrepair of the Mission buildings was, unexpectedly, Robert Louis Stevenson, who arrived in Monterey in 1879 in pursuit of Fanny Osbourne, whom he had met in France some years before and whom he intended to marry. The first complication was that she was already married, and the second was that when Stevenson, always an invalid, arrived at her door after an arduous sea-crossing and an even more arduous train journey across the American continent, he was in such a dilapidated state as to cause Fanny a crisis of uncertainty.

Her affections for Stevenson stabilised but the two respected convention and lived separately in Monterey until her divorce came through. He thus had time on his hands, most of it spent in writing but also in walking around the town and its environs. He was not always enchanted by what he saw, and in a pamphlet wrote, ‘the day of the Jesuit has gone, the day of the Yankee has succeeded.’ His general disapproval found a focus in the state to which the Mission in nearby Carmel had been reduced. ‘As an antiquity in this new land, a quaint specimen of missionary architecture, and a memorial of good deeds, it had a triple claim to preservation from all thinking people, but neglect and abuse have been its portion.’

He would presumably approve of work done after his death, for the establishment has been fully restored to something approaching its former state, the roof replaced, the painting redone, and the cemetery respectfully restored. What he would make of the town is another matter. He deplored the creeping Americanisation, and the process is complete in today’s Carmel, however attractive the town was and is. A residence or playground of the wealthy, it mingles opulence and elegance, but perhaps the one is always reliant on the other. A small town, it boasts over 50 art galleries, and they do not deal in posters. Clint Eastwood was mayor here, and is still owner of two hotels, the Homestead and the Mission Ranch, the latter set in acres of ground adjoining the ocean. Of course it is beautiful.

Although Stevenson spent only a couple of months in Monterey, he left a strong mark and is commemorated by the names of two schools and a museum, housed in a Mexican-period building near where he lived. Cuts in the public budget mean it is open only by appointment, but it has a highly knowledgeable and sensitive guide, Lindy Perez. She takes great pride in showing off the valuable trove of items, including the furniture belonging to the writer’s mother, Margaret, which she took all the way to Samoa, and which was brought to California by Fanny when the house in Samoa was closed. Another unique curio is Margaret’s book of cuttings of items concerning her son.

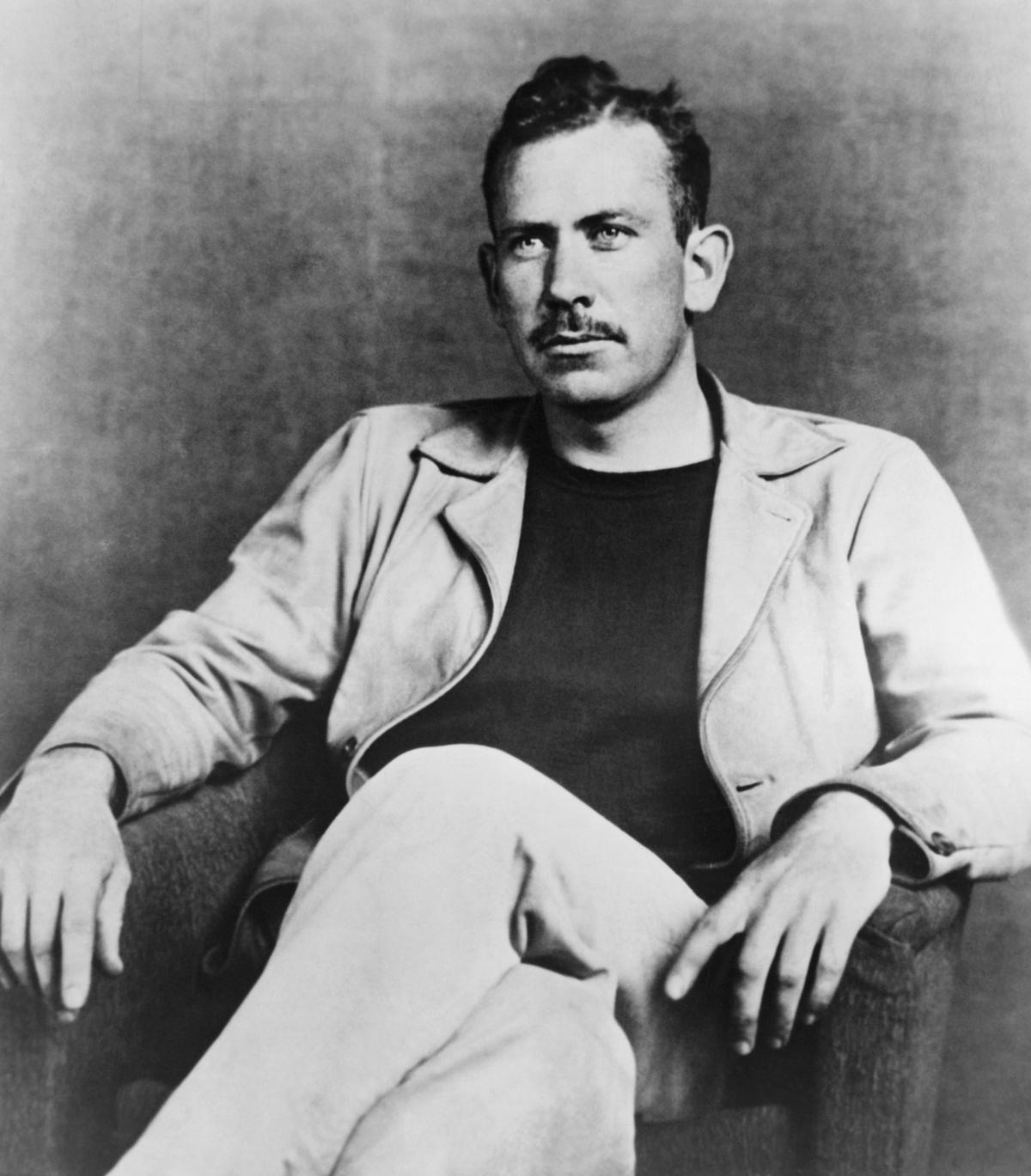

Monterey boasts of being a town associated with two writers of genius, the other being John Steinbeck, born in nearby Salinas where his museum stands. One corner recalls his admiration for Robert Burns, who gave him the title of one of his novels, Of Mice and Men.

Most of his books are set in California, and Cannery Row deals with life in Monterey when it was a fishing port. The main catch was sardines, but the waters were so profoundly over-fished that the once plentiful shoals have disappeared. In the town’s heyday, the ships would sound their signals as they approached land, and the women would take this as a sign to make their way to the dismal canning factories on Cannery Row.

Cannery Row is still there, but is now routinely described as charming, as is Fisherman’s Wharf, where the only boats moored are leisure yachts. Both are lined with boutiques, galleries and restaurants but anyone strolling along the Wharf could pick up a sufficient number of free bowls of clam chowder to nullify the temptation to eat in any of the places. There are dolphins and whales in the breath-takingly beautiful Bay, and skippers who will take you out to see them. The view of the coastline itself is worth the price.

Hearst might have been one of the wealthy Yankees Stevenson found so objectionable, and Hearst Castle further down Highway1 is an arresting fantasy of the sort only the super-rich could indulge in. The man and his projects were satirised by Orson Welles in Citizen Kane, but the film must not be mentioned on his precincts, where the tones used by the guides express awe and respect for Mr Hearst. The awe is justified, the respect more debatably earned. The building stands majestically on a hill top, the fields around contain the zebras which are that remain of a private zoo, the towering edifice is Spanish in inspiration and the massive art collection bought from the indigent nobility of Europe whose power and wealth had passed. Aesthetes may be sniffy, but the experience of being there is powerful and lingering. And Los Angeles itself, the ultimate dream factory, is over the horizon.

Shops across Scotland are closing. Newspaper sales are falling. But we’ve chosen to keep our coverage of the coronavirus crisis free because it’s so important for the people of Scotland to stay informed during this difficult time.

However, producing The Herald's unrivalled analysis, insight and opinion on a daily basis still costs money, and we need your support to sustain our trusted, quality journalism.

To help us get through this, we’re asking readers to take a digital subscription to The Herald. You can sign up now for just £2 for two months.

If you choose to sign up, we’ll offer a faster loading, advert-light experience – and deliver a digital version of the print product to your device every day. Click here to help The Herald: https://www.heraldscotland.com/subscribe/ Thankyou, and stay safe.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here