THE early 1960s was all about insouciance, defiance and declaration, about long hair and short attention spans. It was a time of heightened expectation and change, when class divides would be challenged for the first time.

And who better to capture the mood of the period than the son of an East End lorry driver who left school aged 11? Terence Donovan’s early photographs were not only examples of stunning imagery, they were part of social history.

Donovan was entirely aware, it seems, of the immediate world around him. As a result he not only captured the zeitgeist, but anticipated the future – and his images became iconic.

Now, a retrospective of the photographer's 40-year career, is being staged in London, revealing his photographs which told a story of a Britain in change.

In 1962, Julie Christie was emerging as the most beautiful woman in the world, at a time when the Beatles were still being rejected. But Terence Donovan knew she was more than that. She was the woman every heterosexual male desired, which is why he shot her semi-naked, yet with a slightly startled look on her face: a metaphor for the fact Britain had not yet embarked upon the sexual revolution.

The world at the time was Billy Liar conformity, of humdrum homogeneity, of young people having to rely on their imaginations for adventure, but Donovan’s Christie is a woman of independence.

Donovan was suggesting, rightly, that Christie had no real idea of the impact she could have. But he knew that sex was now on the agenda.

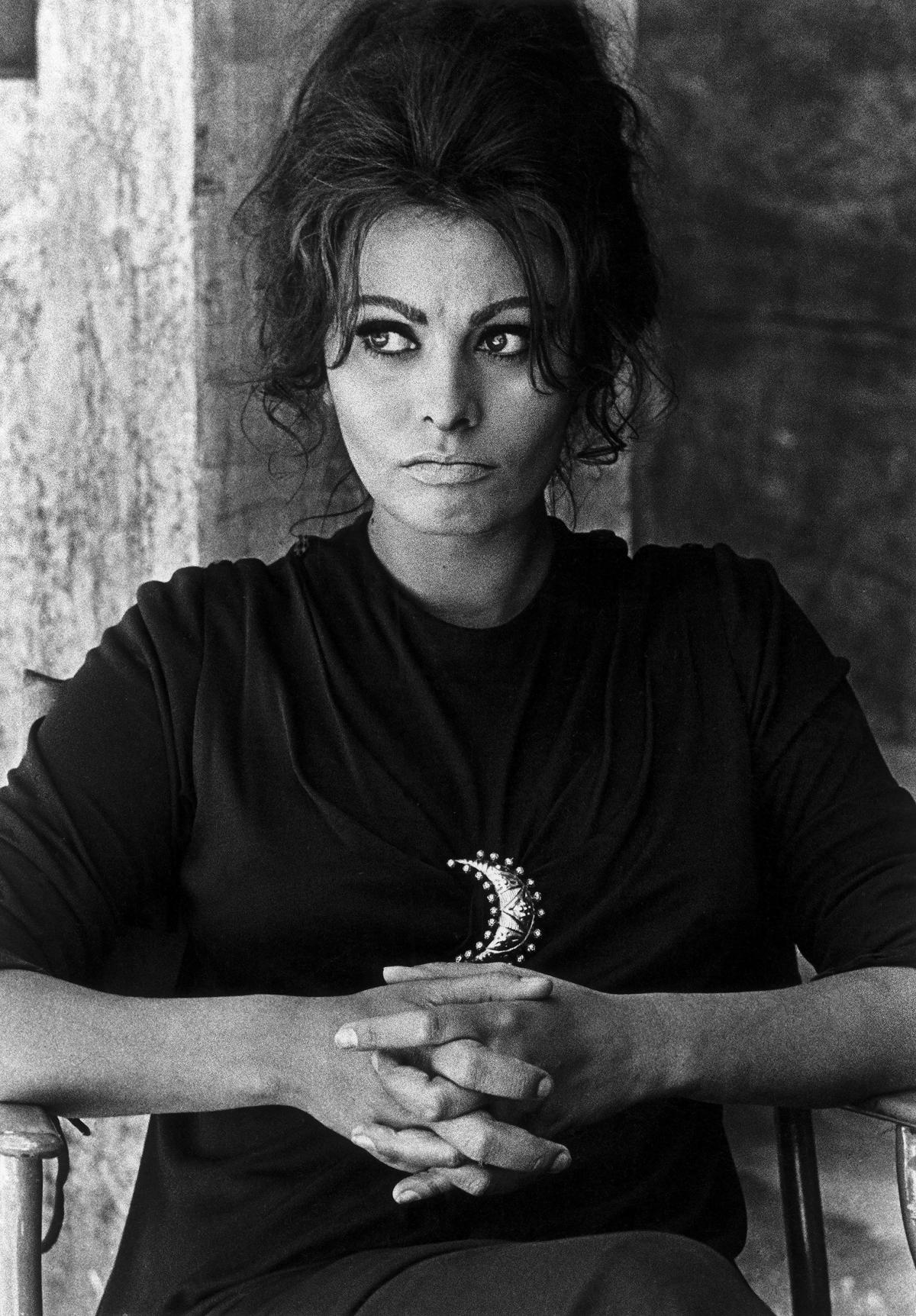

He knew that Sophia Loren also exuded sex appeal, and photographed the star on the set of The Fall Of The Roman Empire, in 1963. However, what he really captured was the Italian’s recalcitrance, an ability not to be objectified, to be part of the movie system, yet remain aloof.

Maggie Smith’s 1964 photograph sees her perched on top of a stool, elfin-like, cocky and self-assured, a young woman astonishingly aware of her own talent, but not to the point of being smug. Pirate Radio Station Caroline had begun broadcasting at the time, in brilliant defiance. What Donovan was saying with this black polo-necked actress was, it was more than OK to have a voice, to be confident; the British trait of hiding lights under bushels had gone. We didn’t have to be contained or embarrassed by the residue of Anthony Eden’s Conservative government of 1955-1957. Young people were a whole new generation.

In 1966 a gamine, stick-thin Twiggy brought a new awareness to modelling. Androgyny was now in, and the sex lines blurred. This was a time when boys could play with dolls such as Action Man and girls could dress like boys if they chose to. Donovan’s photograph revealed Twiggy’s eyes as large as the expectations of modern youth, and in doing so altered the very perception of what it was to be a beautiful woman.

Twiggy, with her clever knowing innocence, and Donovan were synonymous. The photographer liked to shoot glamorous subjects with a backdrop of less glamorous council flats or concrete blocks. He and Twiggy were council, but with an expectation that anything was penthouse possible. However, Donovan knew they weren’t quite there yet.

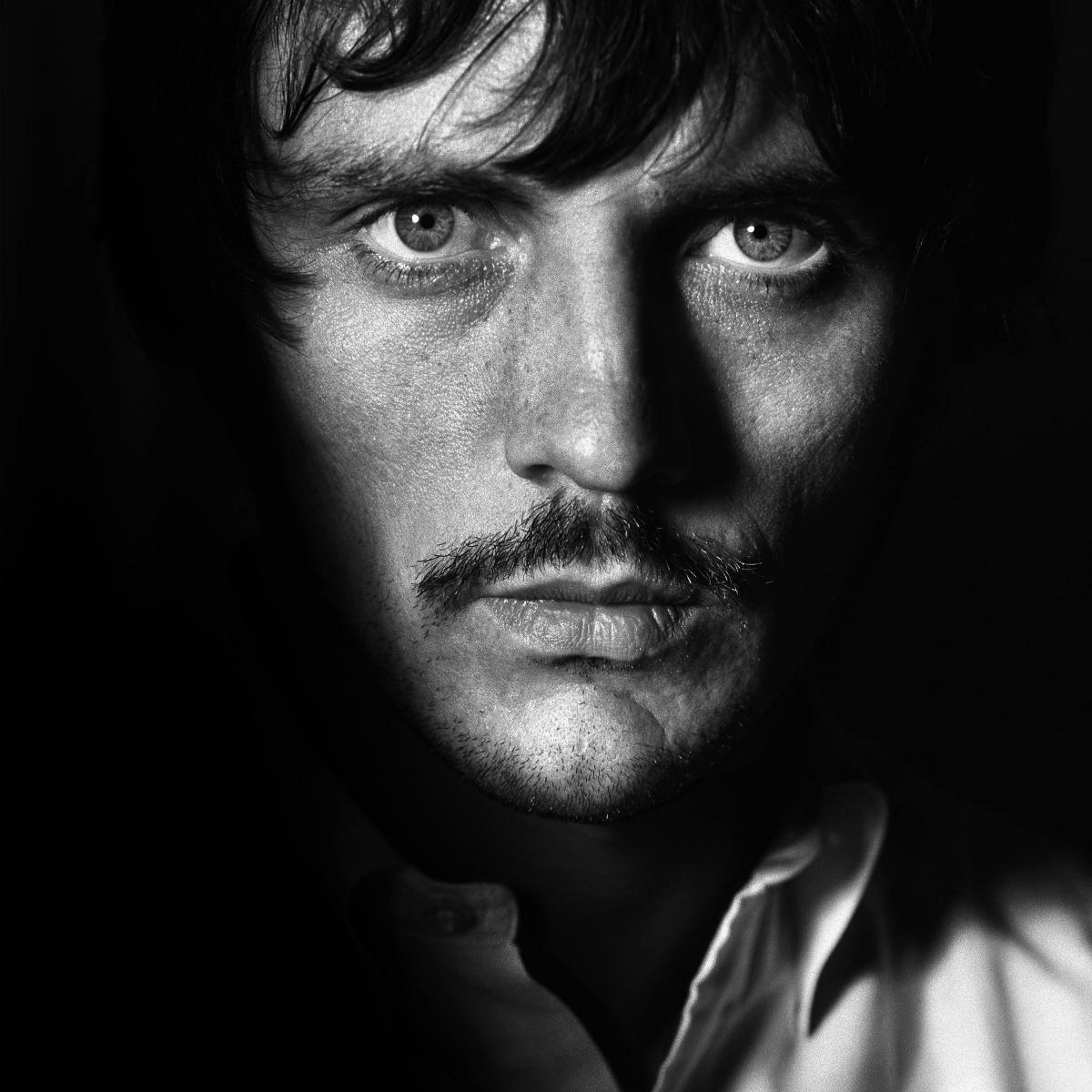

By 1967, when Donovan took Terence Stamp’s photograph, the world had changed. Sex had now been invented and Stamp simply smouldered. The photograph could well be a picture of a South American revolutionary set to march on Havana.

The photograph was taken on the set of John Schlesinger’s Far From The Madding Crowd, in which Stamp starred alongside Julie Christie. (A line in the classic Kinks song Waterloo Sunset – "Terry meets Julie, Waterloo Station, every Friday night" – was rumoured to refer to Stamp and Christie, but songwriter Ray Davies later denied this.)

Life changed for Terence Donovan, the boy from the Mile End Road. In the 1980s he went on to become a video and film director, making Robert Palmer’s cult video Addicted To Love.

And women such as the Princess of Wales and Margaret Thatcher sought him out in the hope that his photographic alchemy would work wonders. And it did. For them.

But it would be fascinating to know what sort of photographs Terence Donovan would be taking today; you’d like to think he’d be part of the zeitgeist, capturing the crises, contrasting the extremes of wealth via celebrity perhaps.

But he was a long-term depressive, and committed suicide in 1996, aged 60. We can only look at his early work and wonder ...

Terence Donovan, Speed of Light, in association with Ricoh, is on display at the Photographer’s Gallery, London, W1, until September 25 www.tpg.org.uk

A new book, Terence Donovan Portraits, is out now, Damiani, £35 www.damianieditore.com

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here