IF YOU haven't heard of John Samson, who died aged 58 in 2004, you may well have seen footage from one or more of the five films which the Kilmarnock-born documentary filmmaker made during a febrile eight year period in his life.

These films, which cast a wide-angled lens over an all-but vanished era, are about people who inhabited the margins of society at a time when there was no social media to keep them connected.

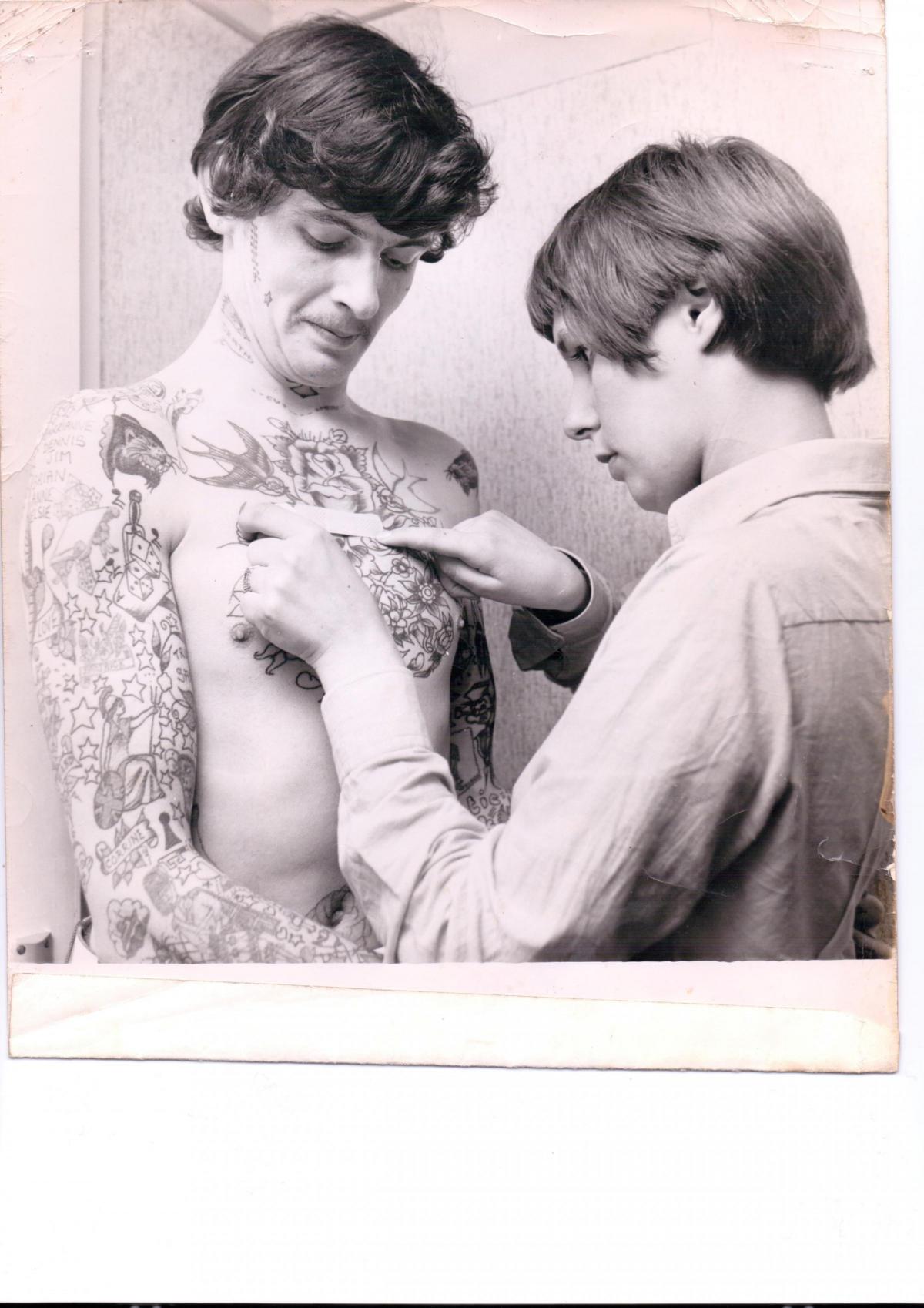

Tattoo (1975) is about the art of tattooing and features artists and their clients. Dressing for Pleasure (1977) explores subject of fetishism in clothing. Britannia (1978) follows a group of volunteers working on the restoration of an old locomotive. Arrows (1979) trails a young Eric Bristow as he goes about his business in the world of competitive darts. The Skin Horse (1983) is an often uncomfortable close-up tracking the sex lives of the disabled. It was screened on Channel 4 and won a BAFTA in 1984.

Samson, shipyard worker and political agitator turned Bohemian filmmaker, is about to be reclaimed by his own folk; rescued from almost-obscurity by Paul Pieroni, senior curator of contemporary art at Glasgow's Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA).

From next Sunday, all five Samson films (with accompanying age-appropriate warnings) will be on show at GoMA's premier gallery space on the ground floor in the first ever museum exhibition of his work. This is also the first time the work will have been publicly screened in Scotland.

Samson moved from Ayrshire to Paisley while still a child and went on to work in the shipyards of the Clyde. Influenced by an aunt with a political edge, as a teenager Samson was involved in various protest movements. He was a spokesperson for shipyard apprentices and in 1961 was arrested at Holy Loch for participation in a Committee of 100 anti-nuclear action.

He met his partner, Linda, in 1963, when she was studying painting at the Glasgow School of Art and promptly fell in with a Bohemian circle of friends, including artists, writers and musicians. Samson taught himself guitar, took up photography, and by the mid-1970s, having attended the National Film School in London, began the cycle of films featured in this exhibition.

Samson was always drawn to individuals and groups operating at the margins of society. As Paul Pieroni says: "John had a history of never fitting in. Be that at docks protest meetings or in other actions. He was always on the periphery, which makes for an interesting artist. He seemed to see a lot more than most people and had an uncanny ability to draw people out.

"His is quite a Glasgow story. He had an authentic working class voice and he was pulled into another world; a Bohemian world. But he was equally interested in darts, tattoos, kinky and locomotives. Everyday stuff is weird. His films show this."

Pieroni first came across Samson in 2008 on online anarchist bookshop, www.christiebooks.com. "I saw the films mentioned in a post and Googled the name John Samson. There was nothing online. That set me off looking to find out more. I ended up showing the films in the basement of a private gallery in London in 2008 and then the following year all five films were shown at the London International Documentary Festival."

Samson went on to work in television after his success with The Skin Horse. Although he always had plans to make more films, according to Pieroni, for whatever reason, they didn't materialise.

The Skin Horse is widely viewed as Samson's finest film. It takes its name from the old and battered Skin Horse character in Margery Williams' 1922 children's book, The Velveteen Rabbit. In the story, a inexperienced rabbit looks to an old horse for answers to life's big questions and receives honest, profound responses.

Scenes from the story, illustrated by painter William Nicholson, are interlaced with at-the-time groundbreaking scenes of disabled people discussing their sex lives.

Samson co-wrote The Skin Horse, which focuses on the Outsiders Club, a dating night for disabled people, with actor Nabil Shaban. Shaban narrates the film in an almost dreamy detached way (Samson didn't hold with voiceovers).

At times, Shaban is shaken out of the dreaminess and addressed the audience directly. When they see him in his wheelchair, he says, people think to themselves, "has he got one and if her has, can he use it?

The online version of the film I watched was followed by a clip from Channel 4's feedback programme hosted by Gus Macdonald, which was screened the following week in December 1983.

One of the guests, Morgan Williams, representing a group called Sexual Problems of the Disabled (SPOD) was critical of the film, describing it as a "filmmaker's film".

Perhaps therein lies the key to Samson and his work.

More an artist filmmaker than a factual documentary maker, Samson paints pictures on film; breaking down perceptions around outsiders who are patronised or excluded from the mainstream.

He was doing that when Louis Theroux and his Weird Weekends were still in short trousers. Watching them now, almost 40 years on, is like gazing back through a looking glass darkly.

John Samson 1975-1983, Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA), Royal Exchange Square, Glasgow, from Sunday 18 September – 17 April 2017 www.glasgowlife.org.uk/museums/GoMA/

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here