SUPPORTERS of the Royal Scottish National Orchestra had rather more of a treat than they were expecting yesterday when they arrived to witness a rehearsal in the orchestra’s new home in Glasgow’s Killermont Street.

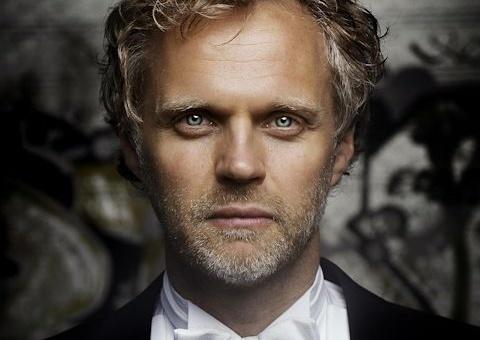

The invitation was to share an hour of the rehearsal time of the musicians and Principal Guest Conductor Thomas Sondergard as they worked on the Fifth Symphony by Jean Sibelius prior to concerts in Edinburgh and Glasgow tonight and tomorrow. The Symphony will be the climax of an intriguing brace of concerts programmed by Sondergard where the music of the Finnish composer was presented alongside that of Beethoven and the songs of Gustav Mahler.

But the enthusiasts at the RSNO Centre were able to share more than just their impressions of the work-in-progress on social media, as the orchestra used the occasion to reveal that Sondergard is to be the next music director of the RSNO, taking over from Peter Oundjian at the start of the season after next.

Canadian Oundjian, who began his conducting career after retiring from leading the Tokyo String Quartet, was appointed music director of the RSNO in 2012, a post he also holds with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra. As well as leading the orchestra through five seasons of concerts in Scotland, Oundjian’s tenure will have included the move from the Henry Wood Hall to the new building at Glasgow Royal Concert Hall and tours to China, Europe and North America.

Dane Thomas Sondergard first conducted the RSNO in 2009, stepping in at short notice to direct Shostakovich’s 11th Symphony, and was appointed Principal Guest Conductor two years later, starting in the 2012/13 season. He has been Principal Conductor of the BBC National Orchestra of Wales from the same time, a contract that will come to an end as he takes up the new position in Scotland.

“When I stepped in to do that symphony with this band, there were so many things that surprised me,” he said last week. “The music was already in their DNA, in their fingers. I realised that in lots of things I was wrong about what I planned to do. It was the same as when I conducted the London Symphony Orchestra for the first time with Prokofiev 6, which they had last played six years previously with Gergiev. In rehearsal they found that again.

“You have to find out how to connect with an orchestra. It is the same in all sorts of jobs: you have to discover how to do your part, how you communicate, what you say and what you don’t say.

“Beginning any new job you have to be focused on what you are doing yourself and finding a routine for how to work.”

He is scathing about the perception of the job of the conductor encouraged by television reality shows, where inexperienced people compete to direct an orchestra.

“What annoyed me most about the Danish version of Maestro was the lack of any sections that explained rehearsals. The main part of the job is in rehearsal, whereas it looked as if conducting was just dancing and waving your arms.”

Sondergard started his musical career as a timpanist, joining the Royal Danish Orchestra on graduation from the Royal Danish Academy of Music, and playing with the European Union Youth Orchestra along the way. Although he says that in modern repertoire composers write for timpani as much more than “as drums”, he always wanted to conduct. His first opportunity came with a performance of Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire in 1996 and music with voices has remained a core part of this work, with orchestrated Mahler songs a regular feature of his RSNO programmes.

In his native Denmark he conducted the premiere of Poul Ruders’ opera Kafka’s Trial and has since been in the pit for Royal Danish Opera productions of Rossini, Mozart, Puccini and Janacek. He has conducted Tosca and Turandot in Sweden and The Magic Flute in Norway. His partner of 17 years is Swedish baritone Andreas Landin.

All of which means that introducing music from opera into the repertoire is among his ambitions for the RSNO, perhaps with an eye to the acclaimed concert performances that Donald Runnicles included in the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra’s seasons at the City Halls.

“Opera is very close to my heart and it is an art form that keeps developing, but opera scores are very expensive; they are a big undertaking,” said Sondergard. “However, it is good to do music that is not so often played, both in Scotland and on tour. The musicians need to be excited by the repertoire.”

The conductor says that he is aware of the RSNO’s already strong relationship with the music of Scandinavia, mentioning Alexander’s Gibson’s ground-breaking cycle of Sibelius symphonies and the tenure of Finn Paavo Berglund as Principal Guest Conductor in the 1980s. One of Sondergard’s first experiences in that role was to accompany the orchestra to a residency at the St Magnus Festival in Orkney, where he was struck by the identification of the islanders with their Scandinavian roots.

So is a Sondergard Sibelius cycle on the cards?

“Could be, but it may be a few years before we can do it. You also have to make sure that you feed the audience with the repertoire that it needs to hear.”

New music is very much on the conductor’s agenda. After the premiere of Martin Suckling’s flute concerto for RSNO principal Kath Bryan, Sondergard met and talked with the composer. He also professes admiration for the music of Sally Beamish and James MacMillan and the work being done at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland.

“Contemporary music is important for many reasons. Musicians play standard pieces differently after they have played a contemporary work, and if we are lucky we find pieces that will be repeated.”

Sondergard’s time with the RSNO so far also covers the move to the new RSNO Centre, which he cannot praise highly enough. He describes how rehearsals of large works at the Henry Wood Hall were hampered by practical considerations like him not being able to see all the musicians from one spot – or they being able to see him.

“I am thrilled the orchestra now has such a great place to rehearse, with natural light and good acoustics. It was difficult to set up a big band at the Henry Wood Hall, now even the back desks of the violins feel included.”

He remains based in Copenhagen, although he says he does not see as much of his home as he would like.

“But it is a perfect place to fly out from. The airport is easy and there are loads of flights. I will still be a guest conductor elsewhere in the world but these are all arrangements we can make work.

“The RSNO will be my major focus, but it is important that we don’t see too much of each other as well as too little. Two weeks in a row and then a gap is good; musicians need the variation. But because I will be music director I will see them far more, and I will be helping to fill these gaps in dialogue with everyone else.

“That is a thrilling part of the job, being involved in who else enters the door – conductors, composers and soloists – as well as in touring and recording.”

With Peter Oundjian at the helm for the orchestra’s planned return visit to the United States next year, Sondergard’s eyes are on Europe for tours beyond that.

“We already know each other but what is most thrilling is that the orchestra comes to trust me in a new job over a period of time. This orchestra is part of the great European tradition – and of course I would like to take the musicians to Scandinavia, to show my home countries what we can do.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here