“Next to Superman, Kirby is probably the most important figure in the history of comic books." Ron Goulart, The Encyclopaedia of American Comics.

“Jack Kirby created part of the language of comics and much of the language of super-hero comics. He took vaudeville and made it opera.” Neil Gaiman, from the foreword of Mark Evanier’s Kirby King of Comics.

JACK Kirby would have been 100 years old today. I’ve been thinking about him a lot recently. Part of that is down to the centenary celebrations, part of it, to be honest, is down to the state of American politics.

When the alt-right and neo-Nazis started to march through Charlottesville earlier this month I wasn’t the only one who tweeted an image of Captain America punching Hitler.

Kirby and his Captain America co-creator Joe Simon drew that famous cover for a comic in 1941. The United States didn’t enter the war until the end of that year.

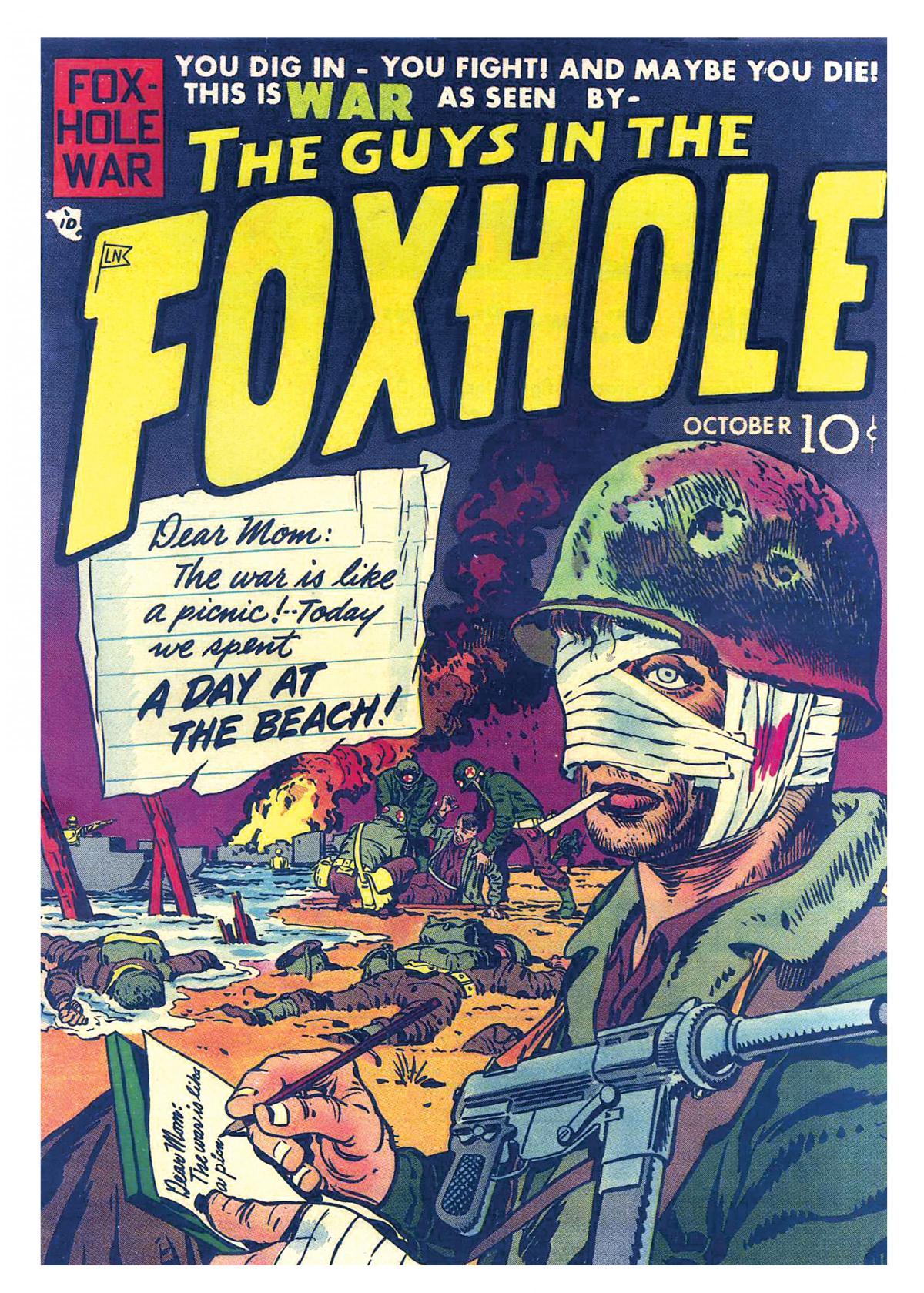

Kirby himself fought in Europe during the war, arriving in Europe a couple of months after D-Day and then taking part in the battle for Bastogne where pneumonia and exposure were as great a threat as enemy fire. Kirby himself suffered frostbite and doctors in a hospital in France considered amputation of one or both of his feet.

In short, Kirby in the field and on the page knew who the enemy was.

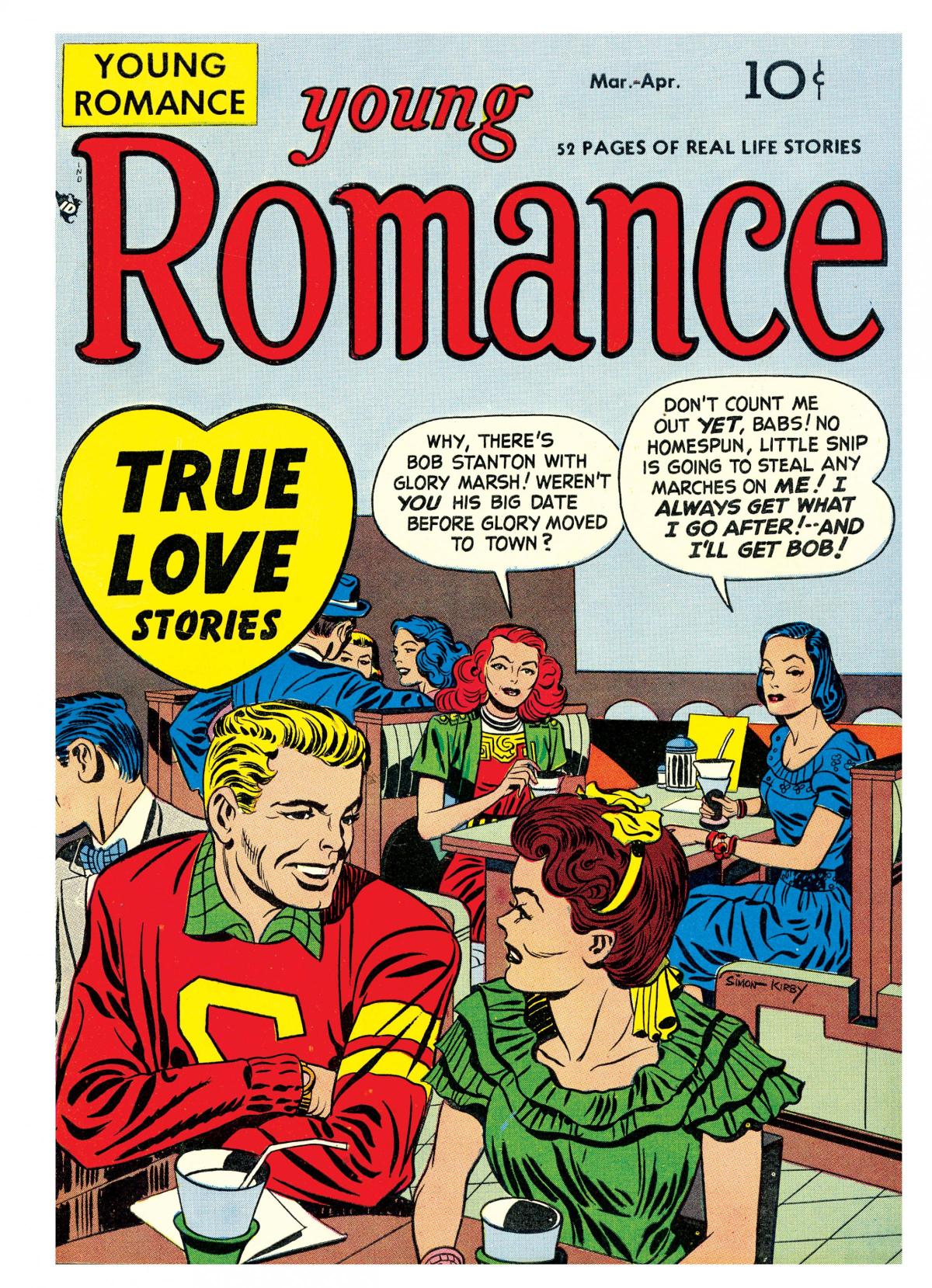

His is an archetypal American story. Born in Manhattan, Kirby was the son of Austrian migrants. Using his eye and his hand he would become one of the prime movers in the rise and rise of the American comic book. From his war and romance comics after the war to the creation of the Marvel universe in the early 1960s.

As Mark Evanier notes in the preface of Kirby King of Comics, his excellent primer on the comic book artist’s work now reissued by Abrams ComicArts: “Jack Kirby didn’t invent the comic book. It just seems that way.”

For those of us born between the end of the Second World War and the end of the Cold War the landscape of our imagination has always been American. From movies to music, fiction to art, comedy to comic books; almost the entire sum of pop culture (apart from the odd British band and European film-maker) was forged on the other side of the Atlantic.

Indeed, now that we live in the Marvel Age of Cinema and Television, much of it was forged in Jack Kirby’s head. But no film or TV series has so far matched the dynamism, kinetic energy or sheer potency of Kirby’s mark-making.

Some of us took a while to realise that. As a 10-year-old I have to admit my own love of Marvel was inspired by Steve Ditko’s art on Spider-Man and Doctor Strange and the flippancy and adolescent humour of Stan Lee’s dialogue. Later I would respond more to the quasi-photorealism of artists such as Gene Colan and Paul Gulacy.

But by the 1980s I began to find something in Kirby’s later work, in its by then primitivist monumentalism, something which made me go back and reconsider his earlier work on The Fantastic Four and Thor.

What I had overlooked was Kirby’s eye for the cosmic, for epic invention. My initial love of Marvel comics was for their street-level comedy and soap opera (Kirby could do both, of course. He was a brash, mouthy New Yorker after all). It took me a while to realise that Kirby brought them their sense of, to paraphrase Gaiman, operatic scale.

“I’m very well versed in science fiction and science fact,” he once said. “I used to read the first science fiction books, and I began to learn about the universe myself and take it seriously … I began to realise what a wonderful and awesome place the universe is, and that helped me in comics because I was looking for the awesome.”

Kirby definitely brought the awesome. Indeed, in his work for DC in the 1970s and Marvel again in the 1980s, “awesome” was his default setting.

Kirby’s story was of course the story of any creative, particularly in the comics industry; one of exploitation, neglect and belated recognition. When Marvel’s owner Martin Goodman sold the company to Perfect Film and Chemical Corporation in 1968 the new owners assumed that Stan Lee was the sole creator of the comics that bore his name.

The new owners thought that Lee drew the comics as well as wrote them. In 1976 Kirby was drawing Captain America for near enough the same money he was getting when he co-created the character back in 1941.

Kirby died on February 6, 1994. His creativity was never properly rewarded in his life time. So it goes.

What matters now, however, is the fact that his comic creations live on, indeed are more familiar than ever. Kirby’s imagination – the one that sprawled across splash pages and double page spreads for the best part of 50 years – is now the stuff of cinema and television. They don’t match the fierce originality of the source, but they wouldn’t exist without him either.

Truth be told, Jack Kirby is dead and living in my head and possibly yours. Even if you’ve never heard of him. Happy birthday Jack.

Kirby King of Comics by Mark Evanier is published by Abrams ComicArts, priced £17.99.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article