Review by Teddy Jamieson

THE December issue of Mad Magazine this year includes a comic strip entitled The Ghastlygun Tinies. It is a punchy, painful satirical take about school shootings in America and the lack of political action to stop them.

Written by Matt Cohen and drawn by Marc Palm, it takes the form of an abecedarian sequence; 26 panels featuring young kids in an American school who, we know, will soon be caught in the path of an unseen shooter. “T is for TINA who’s texting her mom,” reads one entry. We don’t need to see the violence to feel it.

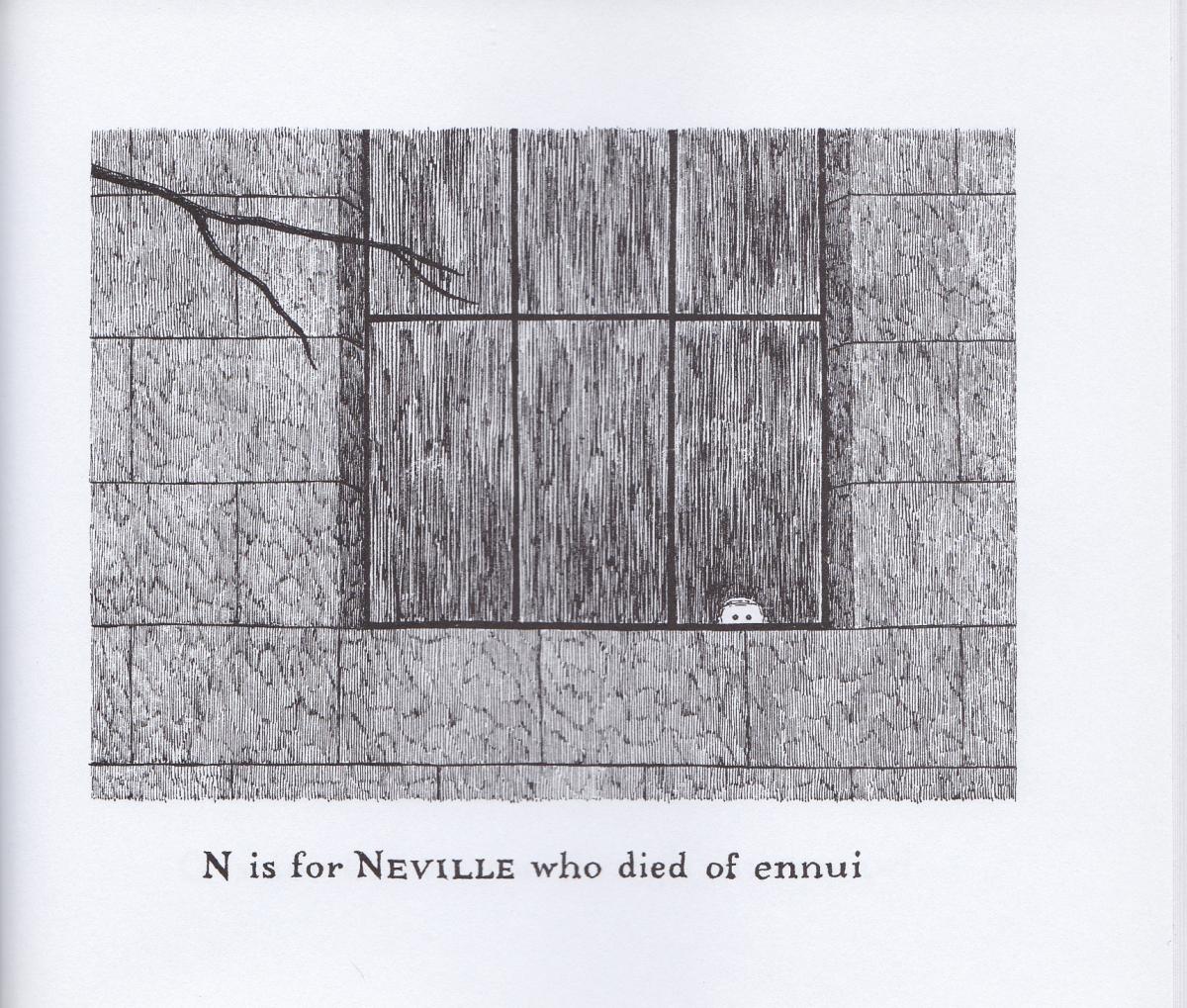

Cohen and Palm’s strip is itself a riff on Edward Gorey’s most famous book, The Gashleycrumb Tinies, originally published 1963. It, too, is a book about the death of children. Sometimes those deaths were violent, sometimes not. (“N is for Neville who died of ennui.”)

School shootings don’t feature in Goreyworld, which tended towards Gothic gloom and precisely rendered visions of antimacassars and impressive moustaches, set, for the most part, in some Victorian or Edwardian country house. But it’s a mark of the texture and reach of Gorey’s work that Mad Magazine opted to reboot it. Gorey’s work is well known enough to be quotable.

It was not always thus. Gorey was the consummate cult artist who sneaked into the mainstream. His work had a dark, delicious, dolour to it that drew on his love of Agatha Christie and Edward Lear and would later inspire the likes of film director Tim Burton and author Daniel Handler (aka children’s author Lemony Snicket).

And yet, when first published, many of his small, beautifully designed books sold indifferently at best. In the post-war boom of American children’s publishing he was more tortoise than hare.

It wasn’t until the success of his stage designs for a Broadway version of Dracula in 1977 and the commission to provide the title sequence for Mystery, an American TV show on PBS in 1980, that his name gained a cachet.

But his real legacy remains the books (there are more than 100 of them) with titles such as The Curious Sofa and The Headless Bust, all of which tap into the same “sinister-slash-cosy” flavour he loved in Christie but are also salted with his own surrealist-stroke-Taoist twist, and always rendered in exquisite cross-hatched detail.

They made for gamey fare for children. Comparisons were often drawn with the cartoons of Charles Addams, creator of The Addams Family, but as Gorey’s new biographer Mark Dery suggests, Addams’s “brand of black humour lite only sneaks a peek at the darkness Gorey peers deep into.”

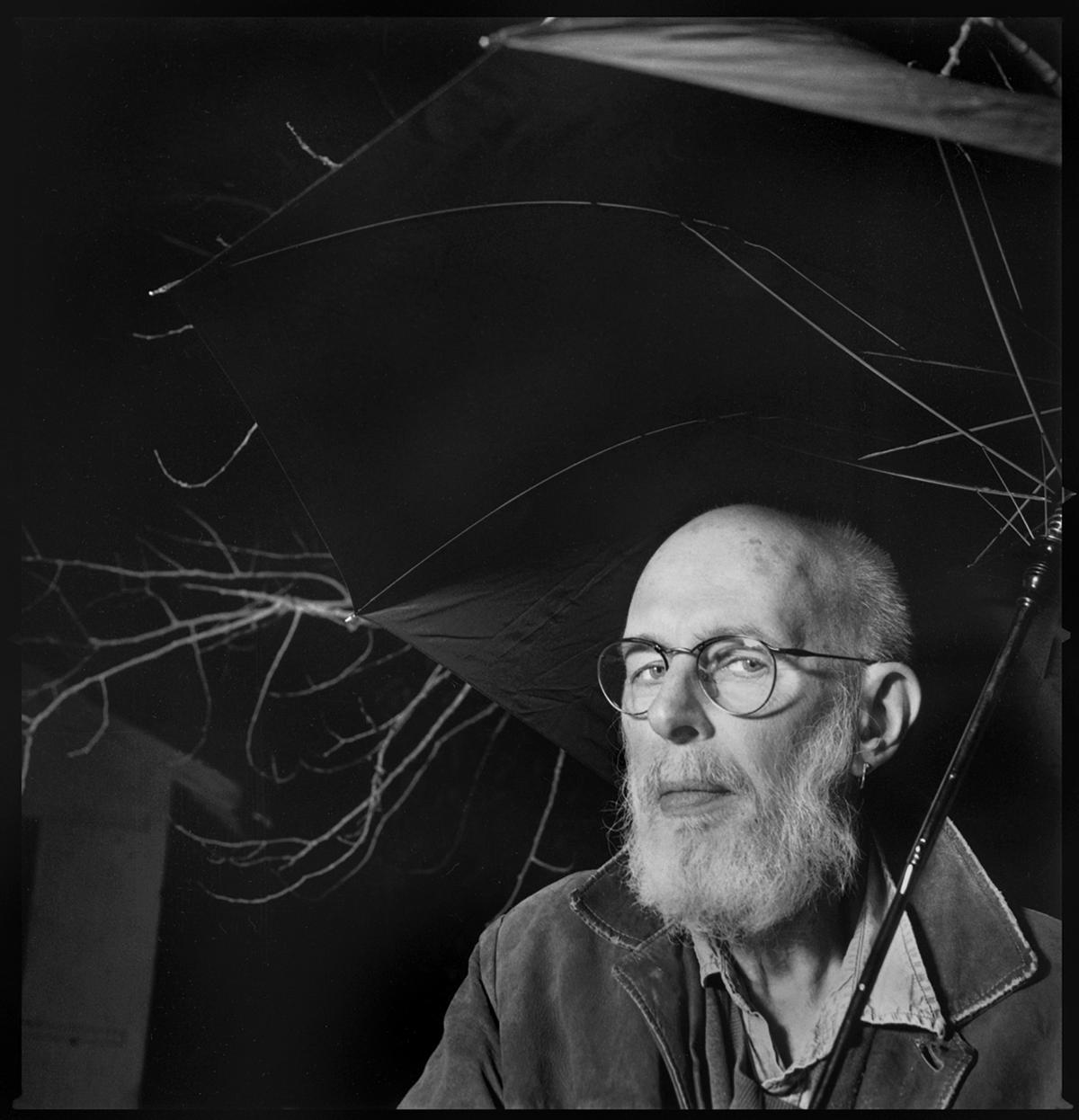

The man behind these strange, wild books is almost as mysterious as the work itself. One of the challenges for Dery in Born to be Posthumous is the fact that his subject is someone whose life was to a large extent interior; someone, too, who was a master of avoidance and evasion when it came to talking about his childhood or love life. “He was a master of misdirection, adroit at dodging the direct question (about his art, his sexuality),” Dery admits.

And yet, Gorey was also someone who hid in plain sight. He would wander around New York – usually on his way to the New York City Ballet – in the 1970s wearing fur coats, scuffed sneakers and an Old Testament beard. After the success of Dracula and the death of his hero, the choreographer George Balanchine, he retreated from New York (leaving a mummy’s head wrapped in brown paper in his New York apartment, which led to the inevitable call from the police when it was discovered) to Cape Cod, where he lived in a house full of his beloved cats, bedecked in poison ivy both inside and out,and with a family of racoons resident in the attic (it was only when a skunk moved in that he finally got around to removing wild animals and poisonous flowering plants.)

All of this offered glorious colour for the many interviewers who interviewed him over the years. But if they tried to dig any further Gorey would slide away from the question.

According to one of his friends Mel Schierman, Dery speaks to “Gorey’s flamboyant persona was a weapon of mass distraction … a shy secretive man’s way of misdirecting the world’s attention.”

But from what? A troubled childhood and questions of his sexuality are the two poles Dery returns to again and again. Gorey was born in 1925. His father, also called Edward, was a Chicago newspaperman, his mother Helen came from money. There’s was a marriage that cut across class lines and was not one built to last. In 1937 Gorey moved to Florida with his mother after his dad left Helen for another woman. Son and father were never on the same page.

Gorey would talk about none of this background noise, but it may be worth noting that often in his books parents were either neglectful or heartless.

Having taught himself to read before he was four years old, Gorey spent his childhood reading Frankenstein, Dracula and a library of 19th-century novels – a good way of making himself invisible to the adults, Dery suggests – which clearly fed into his visual imagination.

At Harvard he met and became friends with future poet and writer Frank O’Hara and haunted graveyards with another wannabe writer Alison Lurie (proving that there is a Morrissey and Linder in every generation).

O’Hara was conflicted over his homosexuality when they first met but he came to terms with it. Whether Gorey did is a matter of debate. “I’m neither one thing nor the other particularly,” Gorey told one interviewer when asked about his sexuality.

Gorey’s tastes – from ballet to the novels of Ronald Firbank – were certainly homosocial. But there is little evidence that he had what you might call a sex life. As Gorey himself once said, could he be called gay if he never did anything about it?

It is a marker of Dery’s assiduity as a biographer that with so many of the details of Gorey’s life at best obscure and sometimes concealed that he has still managed to turn out a book that runs to the high side of 400 pages and one that is as engaging and entertaining as this.

Partly that’s down to his engagement with and enjoyment of Gorey’s work (his close readings of Gorey’s texts are full of insight and obvious pleasure). But partly, too, it’s the mystery of the man that he is engaged with that engages. Because, sometimes, as every detective fiction fan knows, the mystery is more interesting than the solution.

Gorey’s latter years were spent in Cape Cod writing plays to be performed as often as not by the puppets he made or watching episodes of Buffy the Vampire Slayer religiously.

When he died of a heart attack in the year 2000 he was cremated. Some of his ashes were shipped to Ohio to be interred with his mother and aunt Isabel. And yet there is no gravestone with his name on it to be found there.

“In the end,” Dery writes, “it’s only fitting that the man whose art of the unseen and the unspoken, and whose enigmatic life was Freud’s idea of an Agatha Christie mystery, is buried (if he’s buried at all) in an unmarked grave.”

Even in death Edward Gorey remains satisfyingly elusive.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here