The last time I spoke to Kris Kristofferson, in 2012, I asked how he was doing and he made a sound like a saloon bar door creaking open. “Pretty good, pretty good,” he chuckled. “Pretty old.” Back then he was a puppyish 76. He’ll be pushing 83 when he performs three shows in Scotland next week. The title of one recent album, Feeling Mortal, is more apposite than ever.

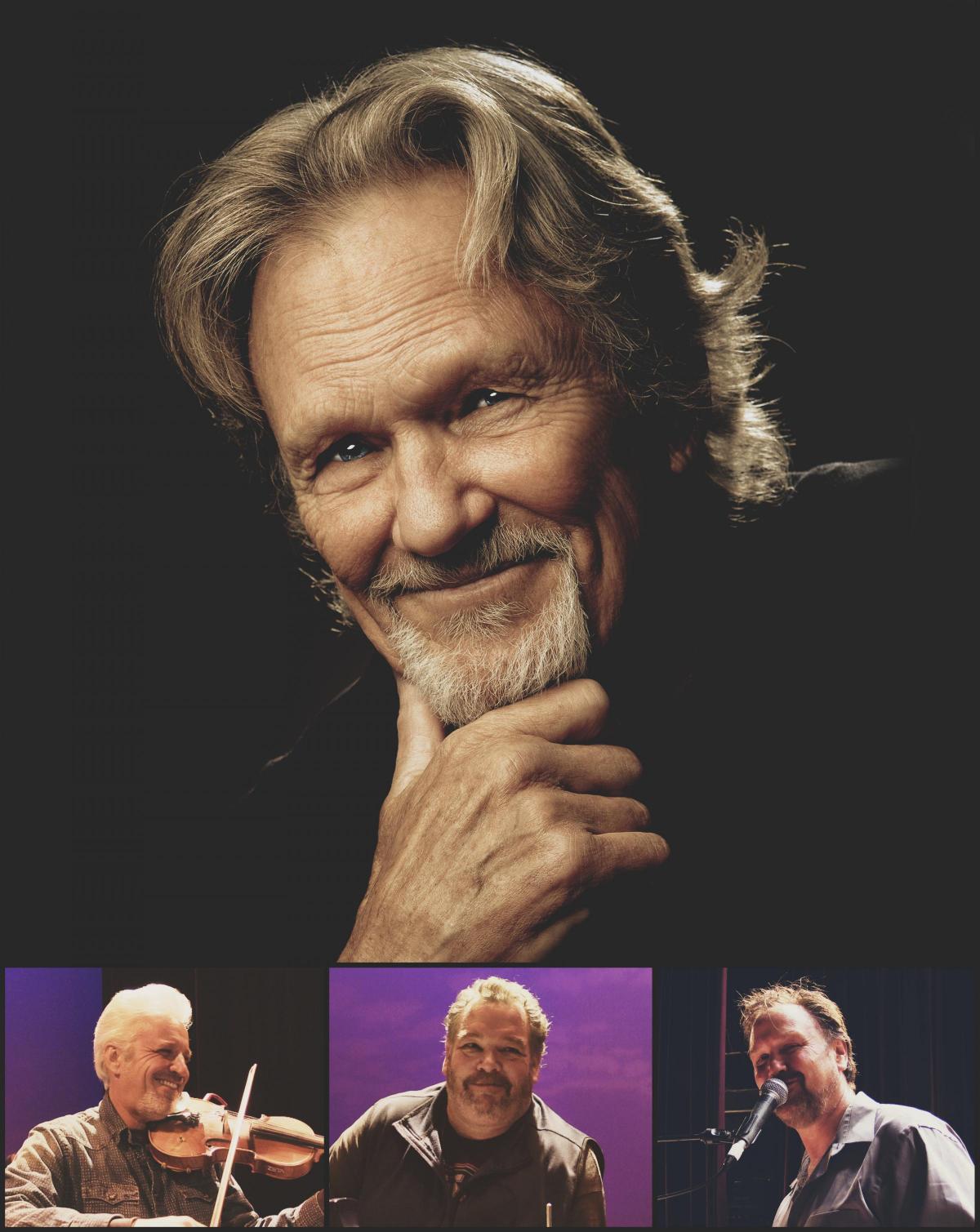

In recent years the legendary singer-songwriter has been battling not just old age but memory loss and Lyme disease, initially misdiagnosed as Alzheimer’s. The condition means he has stopped doing interviews but continues to tour, a smart division of priorities. On his current tour, Kristofferson is backed by a three-piece band which includes guitarist Scott Joss, who previously played with Dwight Yoakam and the late Merle Haggard. Joss says that Kristofferson’s health issues inevitably alter the dynamic of every show.

“It does add something,” he says, speaking from Norway, where Kristofferson has just kicked off his European tour. “Emotionally, everything is pretty close to the surface. There’s not a night goes by that Kris doesn’t get to me in one way or another. I mean, A Moment Of Forever just knocks me over, I have to turn around so that I can shed a tear a little bit. There are two or three songs each night where I have to bite my lip, or step on my foot just to stop from crying.”

His frailty brings fresh context to old classics, but Joss insists that Kristofferson’s memory loss barely affects the mechanics of the show itself. “He stands up there, sings the songs, plays the guitar, has a great time and smiles at everybody. It’s like nothing’s wrong. The only thing is, he doesn’t remember it the next day very much – just little bits and pieces here and there. Other than that, you wouldn’t really know and it’s really not that big of a deal. He’s happy and present in the moment, which is all that really matters.”

Kristofferson is one of the blazing beacons of American music, a rough-hewn renaissance man whose classic songs – Me and Bobby McGhee, Help Me Make It Through The Night, Sunday Morning Coming Down, Why Me Lord? – redefined the language not just of country, but of songwriting in the round. Pithy epigrams are scattered like jewels among the hard earth of his music. His old friend Willie Nelson said he “brought us out of the dark ages”. Steve Earle told me once that Kristofferson “was what I wanted to be when I grew up: a hyper-literate hillbilly. His songs are very plain-spoken in their approach, but there’s this grace to them.”

Outspoken in his left wing views, he has a rare gift for merging the political, social and personal with bruised universality.

He has always looked the part, but Kristofferson was an unlikely candidate for the country canon. “I always felt that I was going to be some kind of writer,” he said, but it was a long time coming. Born into a military family, he spent a year as a Rhodes scholar at Merton College, Oxford, before becoming a captain in the US Army.

After an honourable discharge in 1965 he moved to Nashville to pursue his dream to be a songwriter. He was already 30, and the transition came at a cost. His parents disowned him and it destroyed his first marriage. Perhaps that’s why the best Kristofferson songs contain the sharp, metallic tang of lived experience. Me and Bobby McGhee was written in the Gulf of Mexico, when he was flying helicopters back and forth to the oil platforms. This was a man who understood the price of freedom.

In Nashville he undertook what he called his “graduate work”. He combined writing songs for publishing companies with a number of odd jobs, including working as a janitor at Columbia studios, where he befriended Johnny Cash and watched Bob Dylan recording Blonde on Blonde. The proximity to genius helped him to blossom as a songwriter, as well as make key contacts. When Cash had a hit with the beautifully defeated Sunday Morning Coming Down in 1970, “suddenly everything seemed to be turning out for the best.” Before long, Kristofferson was a recording star in his own right.

His hip new take on country music caused a stir. These were songs littered with drug references, liberated sex and counter-cultural affiliations, closer to Dylan and Leonard Cohen than the Grand Ole Opry. It’s fair to say the Nashville establishment did not immediately warm to this upstart hippie freak.

“I wasn’t conscious of working at being controversial, I was just expressing myself as best I could,” Kristofferson told me. “I think I was aware even then that the soulful part of songwriting that I identified with would eventually prevail.”

Musical genius or a wasted talent? In search of the real John Martyn

As his star rose, he forged a highly successful second career as a limited but charismatic leading man in films like The Last Movie, Cisco Pike, Convoy and Songwriter. Bradley Cooper successfully rebooted A Star Is Born last year with Lady Gaga, but Kristofferson definitively nailed that hirsute, hyper-virile, messed-up male shtick in the 1976 version, co-starring Barbra Streisand, for which he won a Golden Globe. “From then on it was all a big blur,” he told me. “I was very lucky to be doing movies and music, each one would pick up the slack for the other. The downside is that when you’re famous you have a lot less alone time, which is good writing time.” Arguably, by the 1980s he was better known as an actor than a musician. Arguably also, the music suffered.

When Kristofferson played in Edinburgh a few years ago, he introduced one song with the immortal line, “This is for my kids – and all their mommas.” He divorced his second wife, the singer Rita Coolidge, in 1980, and today lives on the Hawaiian island of Maui with his third wife Lisa, whom he married in 1983. Altogether he has eight children. On tour, he travels with Lisa and a rolling assortment of kids, grandchildren and friends. “They’re very family orientated people, very down to earth,” says Joss. “We hang out at dinner and breakfast. It’s a real easy thing.”

On his last few studio albums, Kristofferson formed a productive partnership with Don Was, but more recently the emphasis has been to drill down into his mighty back catalogue. For Joss, the current live show brings his career full circle.

“It has actually come back to how these songs were written,” he says. “He’s a songwriter – that was the first gift that was given him, and that’s predominantly what he remains. All the other things were just added bonuses. It always goes back to the songs and, at this point, they’re stripped down to the very essence. Nothing gets in the way. Nobody is trying to be a sex symbol or the rock god. We’re just presenting these songs as the little works of art that they are, and we’re lucky enough to still have this guy here who wrote them, singing them from this very sensitive point now.”

This tour may well be the last time we see Kristofferson on stage, but it’s far from a sentimental last waltz. It is, instead, a vital reckoning between a man and his music. It helps that he’s never had much of a voice to lose. Just before going on stage in the 1980s for a gig with the country music supergroup, The Highwaymen, Kristofferson turned to Willie Nelson and confided, “My voice isn’t in such great shape tonight.” “How can you tell?” fired back Shotgun Willie.

He and Nelson, who is a spry 86, are now the last gunslingers in town. Their fellow Highwaymen, Johnny Cash and Waylon Jennings, are long gone. Other close friends like Merle Haggard, Muhammad Ali and Fred Foster have also passed. Yet Kristofferson gives every impression of being a man finally at peace with himself.

Lau's Kris Drever: 'I can't escape writing about a sense of place. It must be a Scottish thing'

“I feel so grateful,” he told me in 2012. “I’ve got a family, a whole bunch of kids who love each other, and I feel like I’ve got plenty of respect for my work and I still fill houses when we go out and play. I can be proud of all the things I got to do.” He made it through the night. It’s all sunshine from hereon in.

Kris Kristofferson & The Strangers plays Usher Hall, Edinburgh (Tues); Aberdeen Music Hall (Wed); and RCH, Glasgow (Thurs)

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here