SIR James MacMillan is tired. Composing may be a solitary activity but conducting is not, and it’s that which has tied him to the Glasgow Royal Concert Hall since 8.30am today for a performance involving schoolchildren from across Glasgow and the west of Scotland. It’s now a little after 4pm, the youngsters have packed up their instruments and are filing noisily out of the venue, and Sir James is finally sinking into a seat in the café and enjoying what I’m sure is not his first black coffee of the day.

It's no surprise that he’s busy. He turns 60 on July 16 and as well as two books celebrating that landmark – one by him, published on his birthday, and one about him – the Edinburgh International Festival is honouring him with a retrospective of sorts. The Festival is also hosting the first performance of a new work, his Symphony No 5: Le Grand Inconnu. If the title hints at a big theme – it translates as The Great Unknown – it’s typical of a man whose music is often infused by and related to his own deep religious convictions and questing spirituality. “Numinous” is a word he uses a lot.

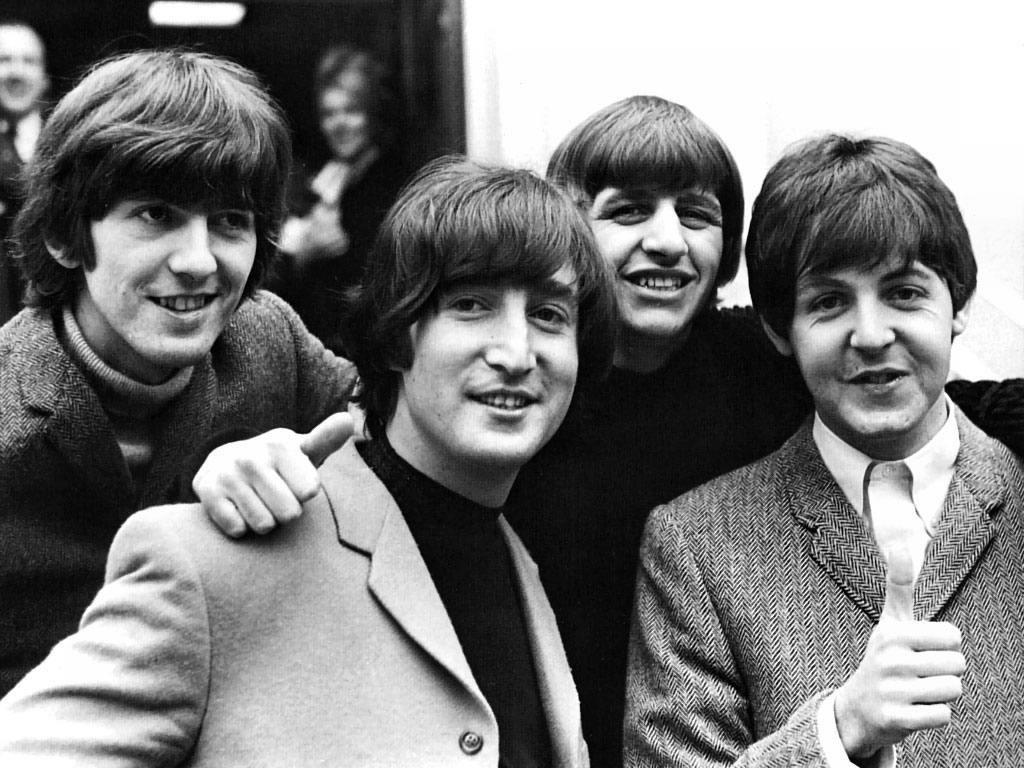

Right now, though, he’s telling me about The Beatles. His musical awakening came aged five or six at St Mary’s Catholic Cathedral in Edinburgh when for the first time he heard what he later learned was a Gregorian chant. It was an electrifying experience at an important age. Music and religion have been fused in his imagination ever since. A few years on he was handed a recorder at primary school and there discovered his own rare facility for music-making. But at home in the Ayrshire mining town of Cumnock he was encountering something a little less spiritual: the Fab Four and the pop sounds of the Swinging Sixties.

“In the very early stages I was influenced by an aunt who was a teenager in the 1960s,” he says. “It was my aunt Ann, who was my mum’s sister. We used to share a lot together and she was always playing little 45s, mainly The Beatles, but lots of other things. So I was hearing The Beatles very early on and getting something of that visceral excitement, and seeing how it affected my aunt who was just a little bit older than me. So pop music has always been there. I’ve never been down on pop music as classical people can be. It’s just part of the background, part of the fabric.”

The love of sacred and liturgical music continued but so did his liking for the stuff coming out of the radio. As a long-haired pupil at Cumnock Academy he joined a rock group and, perhaps predictably, his tastes verged on the Baroque.

“When I became a teenager in the early 1970s it was the tail end of things from the 1960s,” he says. “I remember my pals liked things like Cream, Jack Bruce and slightly more exploratory things like the Mahavishnu Orchestra and John McLaughlin. I remember coming up here when I was 13 or 14 to see him, with Billy Cobham on drums, and just being blown away by the sheer musicianship.”

Even today one of his “guilty pleasures”, as he puts it, is Tales From Topographic Oceans, the sprawling 1973 concept album by English prog-rock band Yes. Wonderfully pretentious, it’s based on a series of ancient Hindu texts. He loved it when it was released but now when he listens he can’t help wondering why. “I can still feel the teenage excitement but it doesn’t work, either as classical music or as popular music.”

I CONFESS I didn’t expect to be sitting here talking to Scotland’s foremost composer about Yes and Cream or picturing him bopping round a Dansette to A Hard Day’s Night, but Sir James is easy company and makes free with the stories. It’s a good attribute for a man who is also a writer.

The book about him is by Phillip Cooke, head of music at Aberdeen University. The one by him is A Scots Song, not so much a memoir or an autobiography as a collection of essays. They sketch in the important parts of his life story but deal mainly with his thoughts on the music of the 20th century and his own journey through its later years and the opening decades of the 21st.

“There might be an autobiographical skeleton in the piece, but it just allows me to jump off into topics that I’m very interested in, mainly about music or where the music comes from or what inspires it,” he explains. “It does trace a life, from growing up in Cumnock and all the rest of it, right up to the present day and things that have happened recently. But still looking at the power of music – the importance of music generally, but also for me.”

More specifically he has a lot to say in A Scots Song about modernism and the avant-garde, much of it questioning and some of it critical. The arguments can verge on the esoteric at times but at heart he takes issue with a form of artistic practice which rejects the past, seeks to impose limits and strict orthodoxies on the present, and too often drags politics into the mix. Rather mischievously, he also stresses the numinous quality underpinning the work of hardcore modernists such as Igor Stravinsky, Arnold Schoenberg and John Cage. Did I know that Cage’s most famous work – four and a half minutes of silence titled 4’ 33” – was originally called Silent Prayer? I did not.

Sir James, for his part, is a noted fan of the past. He describes himself as a “somewhere” composer, that somewhere being Scotland, and he has made it his business to delve deep into the country’s musical traditions for inspiration. “It has made me who I am,” he says. “It has shaped, sometimes subliminally, the music I make”. He calls this process “probing tradition – not identity as such in the ethnic sense, but that deep reservoir of music that hadn’t really been considered an important thing until the folk revival.”

That same attitude has seen him turn as well to the work of 20th century English composers such as Benjamin Britten and Ralph Vaughan Williams, not considered as fashionable or as important then as they are now. Sir James, then, was always a composer interested in pushing boundaries but who had no qualms about borrowing from the past in order to do it.

On the European mainland it was a different story. That sort of localism was seen as disturbing or, worse, reactionary. He tells me about visiting Darmstadt in 1980 for one of the German town’s famous music schools, a biennial symposium for modern classical composers. He recalls how astonished he was that the German composers present seemed to be caught up in “this identity politics stuff”. Somebody “quoting” Mahler, or even alluding to a specific key associated with a certain type of music, could cause an uproar. If you sounded too German, you were booed. It’s chewy stuff and, I suggest, a bit too subtle for even the most the most dedicated classical music fans.

“Exactly,” he says. “But this is the world of the avant-garde. And I rejected that.”

THIS year sees another significant Sir James-related anniversary. It’s 20 years since he delivered a headline-making speech at the Edinburgh Festival titled Scotland’s Shame which tackled the subject of anti-Catholic sentiment in modern Scotland.

“It’s something I did notice and feel and was compelled to speak about 20 years ago,” he says. “The title of the speech was Scotland’s Shame: Anti-Catholicism As A Barrier To Genuine Pluralism. The second bit gets ignored or forgotten about. I think I genuinely felt that anti-Catholic feeling was not good for the entire society in the same way that Islamophobic attitudes aren’t good for the bigger society [today].”

It’s a point he returns to in a roundabout way in A Scots Song. At one point he writes that “patriotic modern Scotland” seems “embarrassed or bewildered by its Catholic beginnings”. But isn’t modern Scotland far more embarrassed by the memory of John Knox and the harsh strictures of Calvinism than it is by the country’s pre-Reformation history?

“That’s true too,” he concedes. “Maybe we’re embarrassed by both. Maybe it’s our Christian heritage that’s embarrassing to liberal, secular Scotland. Certainly at the time of my speech there was a lot of discussion around what had been written out of Scotland’s engagement with its past”.

That’s not to say he hasn’t had “issues” with Calvinism. But, he stresses, “I’m much more at ease with it now because I recognise a great strength in the Protestant Church in Scotland and what it has given to the Scottish character. I see where people are coming from on that. Maybe it’s unfair. Maybe the treatment and disdain for the likes of John Knox is as unfair and self-debilitating as our negativity towards pre-Reformation Scotland.”

If that grinding sound is a can of worms opening, it’s probably time to move on. Sir James is happy to talk about music teaching in schools, his concern that a dropping of standards will result in a lack of attainment (“There is an anxiety that the gifted in Scotland might miss out because the curriculum is not pushing them”), social mobility, the health of the Edinburgh International Festival, how the “gentrification” of the working class is impacting on organisations such as brass bands and the towering achievement that is the National Youth Choice of Scotland (“now attracting international attention and that’s extraordinary for a young person’s chorus”). But he no longer feels the need to pitch in on wider societal issues. Or, as he puts it, he’s now prone to “shutting my face about things which are not related to music”.

A Communist in his youth and a Labour supporter by family tradition, he has now also become politically agnostic. The youthful certainties are gone, he says. “I don’t know quite what I believe and I’m not that bothered any more. I enjoy the company of people who at one time I would have shunned.”

One example is conservative philosopher Sir Roger Scruton, rarely far from the headlines thanks to his opinions on everything from animal rights to China.

“I know him quite well and we have relaxed conversations. He’s a fascinating man and a brilliant brain … He’s on a journey as well, theologically, but he’s someone I would never have had anything to do with 30 or 40 years ago. I enjoy the difference. It’s about finding people who are different and appreciating them for who they are.”

OTHER things happen as you age besides losing the political certainties of youth. Turning 60 is a time for reflection as well as celebration and along with the cards and good wishes – and, in Sir James’s case, books and concert performances – there are the inevitable encounters with grief that ageing brings. Sir James’s father died this year, so did his Beatles-loving aunt and just today he heard that the father of a musician friend had passed away. And in 2016 came perhaps the cruellest blow of all: the death of his five-year-old grand-daughter, who had been born with a rare brain condition that had left her severely disabled.

How have these events, and the process of ageing, affected his relationship with his faith? Births are always a time to take stock, but for those with faith it’s death which is at the business end of religion.

“I wouldn’t have known how to deal with a question like that even five years ago,” he replies. “But now things are accelerating. My kids are growing up, my eldest is 28, one is married already, another is getting married this summer. My father died this year, my beloved aunt died this year, and I’m meeting my old pals from Cumnock at funerals now. It’s the main place we meet, and we’re all feeling the same thing, experiencing the same thing – having these final conversations with our parents knowing that they’re soon going to be no more. You live with it daily and we’re in the final furlong I suppose, not to be too depressing about it. I could luckily have another 30 years, that would be great. But 30 years ago to me just feels like yesterday.”

Has that altered his perspective on his faith?

“I can’t decide. When people ask about my grand-daughter they say: ‘Did that knock your faith?’ and I wonder: ‘Did it?’ I think if anything when a catastrophe like that happens the faith, or at least the structure of the faith, kicks in … the whole experience of catastrophe and calamity is subsumed into the requiem mass. Suddenly those texts which I’ve lived with all my life – and I’ve set and sung many of them – mean something because it’s to do with a member of the family who has died.”

After years spent living in Glasgow, Sir James moved back to Ayrshire four years ago. He could have lived anywhere – New York, London, Berlin – and when he was younger he imagined he would as his career took off and the world and its orchestras opened up to him. But as well as playing well to his idea of “localism”, it was family ties that kept him rooted in the west of Scotland. He met his future wife Lynne at Cumnock Academy and they took the decision to raise their three children in Scotland. She didn’t want to move, he realised he didn’t have to.

“I could have been happy anywhere as long as they were with me,” he says. “But composing is a very solitary existence. I can do it anywhere, so why not in Glasgow or North Ayrshire? I do travel a lot and I do have this complementary life as a performer, or conductor, or speaker, or lecturer. I do all that. But there has to be a groundedness and that groundedness, in retrospect, has worked for me.” He pauses for a beat before he sums it up. “I like the feeling of being here.”

James MacMillan: A Scots Song is published on July 16 (Birlinn, £7.99); The Music Of James MacMillan by Phillip Cooke is published on July 13 (Boydell Press, £30); Sir James MacMillan At 60 is a series of concerts in the Edinburgh International Festival (August 2-26).

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here