IT IS very liquid the way life flows into art and art flows into life in the world of Pedro Almodvar. Near the beginning of the director’s quietly gorgeous new film Pain and Glory there is a sequence showing Antonio Banderas sitting, arms outstretched, on a chair in a swimming pool, the water above his head.

It’s an image that came directly from Almodovar’s own experience. A while back the Spanish director was having problems with his back. So much so that he needed an operation.

That summer at some point he would also end up under the water in a swimming pool once a day. The water supported him, he found. For a moment his back pain went away. “It was the best moment of the day for me,” he recalls now.

And because he’s a film director and because he thinks in pictures, on one of those days he asked someone to take a picture of him in the swimming pool. “Because,” he says, “I thought, this is a good cinematic image.”

And, so, life is transmuted into cinema. It was ever thus with Almodovar. Back in the 1970s and 1980s, the director was a young gay man living a wild life in post-Franco Madrid and making films that were casually shocking and wilfully provocative as a result.

Now, as a man on the verge of 70, he makes beautiful films about the pains of ageing and love and desire and loss. If you look closely you can possibly see him in all of his films. But maybe no more so than in Pain and Glory. Already it is being hailed as the most personal he’s ever made.

Not so surprising. It is, after all, the story of a film director Salvador Mallo, played by Antonio Banderas, who is facing old age and is suffering from various ailments, including back pain. He is also looking back on his life – his childhood in post-war Spain when he was a soloist in the choir (as Almodovar was) and when he began to realise that he was gay; and his life as a young director in Madrid during the Movida years – and remembering old friends, old lovers and his own mother.

It’s a film full of men on the verge of tears, men of a certain age kissing each other passionately and of men counting up the cost of the way they have chosen to live. It takes place in a recognisably Almodovarian universe, full of familiar faces and covetable décor (in another life the director could have been an interior designer). This time around the narrative is less melodramatic than usual, but it has a real emotional heft that slowly unfurls alongside Mallo’s memories. Almodovar makes the comparison’s to Fellini’s 8 1/2 explicit by showing a poster of the Italian director’s movie at one point.

Banderas is very good and very different as Mallo, it should be noted. But it’s difficult to avoid the fact that he even looks a bit like Almdovar. Same haircut, same beard (albeit there’s a bit more pepper in comparison to Almodovar’s salt).

It all leaves you wondering what in the film is real and what is fiction (I’m guessing smoking heroin is the latter, but maybe Salvador’s loneliness might be closer to home – Almodovar lives alone in Madrid, after all).

It’s this overlap between life and fiction that inevitably I want to probe when I meet the director in London a week before the film opens.

Read More: Mike Leigh on his latest film Peterloo

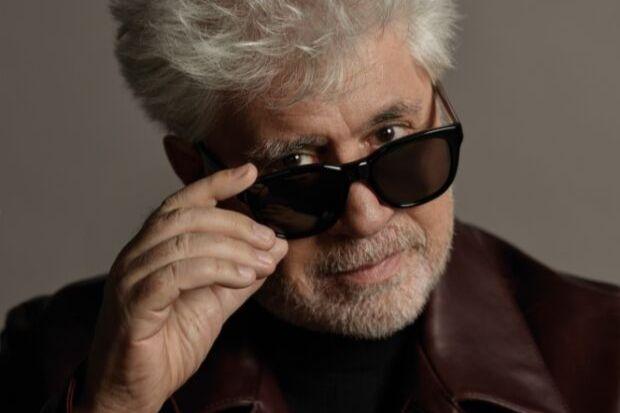

I first see him standing with his interpreter Maria. He is instantly recognisable. Mustard bomber jacket, patterned shirt possibly borrowed from a new wave guitarist circa 1979, and the silver hair and beard that has almost become a brand image, like David Hockney’s glasses or Andy Warhol’s wig.

Almodovar, perhaps alongside Quentin Tarantino, is the last of something. That something might be the notion of the film director as auteur and public figure (the likes of Claire Denis and the Dardenne brothers are the former but not the latter).

It is the morning after the night before when Pain and Glory received its UK premiere at Somerset House in London. Today’s newspapers are full of images of Almodovar with his stars, Banderas and Penelope Cruz, who in flashbacks plays the mother of Banderas’s character.

The director seems to have enjoyed the experience. And the publicity. “Penelope came last night all dressed gorgeously and looking amazing, and today all of the fashion magazines are talking about her,” he says, approvingly.

Then again, he adds, “I don’t think about this when I called them to work. I just think they are the best for the characters.”

And they are characters. This is not his story, he says. But the story draws on parts of his story. The obvious first question then, given Salvador Mallo’s list of ailments – back pain and depression most notably – is to ask his creator, “Pedro, how are you? How are you feeling?’

“Yes, yes, I am okay,” he says. “I’m not as bad as the character in the movie. I have a few problems, but, no, basically I’m fine.”

In short, Salvador Mallo is not him. Or not quite at any rate.

Also, despite the visual similarity, Banderas is not, according to his director, giving us his impersonation of Almodovar. He didn’t steal some of your mannerisms then?

“I don’t think so. I gave him permission to imitate me. It’s the first time I’ve ever done that with an actor. But I think what happened is Antonio has actually reinvented himself as an actor in this film.

“There were props that I gave him. Sneakers that are mine. A polo shirt. His character lives in a house that is a replica of my house. It’s my furniture and my artworks.

“People I know in Madrid who have seen the film say: ‘I’m not seeing Antonio, I’m seeing you. But he’s not imitating me. Rather he is permeating himself in the character he is creating.”

Almodovar sometimes doodles while he talks. And he likes to talk. In conversation he might starts off speaking English and then, when he wants to explain an idea in detail, he will jump back into Spanish and give long discursive answers hoping that the interpreter Maria can keep up with him (to her credit, she always does).

Ask him about the origins of his latest film and he starts with that image of the swimming pool and then how the current of that led him to a memory of the river where his mother and the women of the village he grew up in in La Mancha would go to wash their clothes. “I have incredibly vivid memories of that moment; the women working and singing as they do in the film. My memory is very luminous and happy.”

That, he thought, offered a bright contrast to the sombre present he was depicting. And then he wove into the structure a story about a falling out with an actor (this is from experience) and a story from the 1980s that isn't, but reflects a world he knew, as well as a flashback to Salvador’s mother (played by another Almodovar regular, Julieta Serrano) telling him that he has not been a good son.

That was not Almodovar’s own experience either, he is quick to point out. And yet filming that scene, he admits, he found himself very close to tears. He realised that somewhere in there was an emotion he recognised from somewhere in his childhood.

“What I am expressing in that scene is not the strangeness in my mother’s eyes when she looked at me, but in the eyes of other villagers looking at me as if I were an unusual being and at school as if saying: ‘You are not a normal person’. Their glance said that to me.

“That represents the strangeness I experienced as a child and saw in the looks of others.”

He goes on to say more but I want to talk to him about that “strangeness,” I say. What was this “strangeness” his fellow villagers were seeing? Was it his sexuality? Was it his creativity?

“Everything together,” he thinks.

The young Almodovar was a voracious reader and a lover of cinema from an early age. “I remember talking about cinema on the patio at school to fellow pupils. Some were fascinated and some thought I was mad.

“And obviously,” he adds, “there was the issue of sexuality which I had begun to be aware of around the age of 10.

“And all this made me a different child. And as a result, I lived through the cruelty of people around me. It wasn’t normal to be like I was. At least not in the fifties and sixties in Spain.”

Well, indeed. Spain was still a dictatorship at this point. General Franco ruled over a repressive, conservative, backward-looking church-dominated country.

Almodovar came from working-class stock. His father ran a petrol station and his mum worked in a bodega. But their son stood out.

“I was a star at school. I would speak in public. I was a soloist in the choir. Very good grades. I wasn’t good at sport.”

In short, he says, he had interests that were not shared by the other children. And that was noticed.

“Small communities are very cruel when facing difference. And this is especially the case with children. Bullying is part of childhood. They explicitly tried to demean me.

“I was a strong boy, fortunately. And I was able to confront them. Sometimes I had to confront them physically. I was as masculine and brutish as them. I stopped the bullying because I confronted them.”

Still, it left its mark. This was the world that Almodovar was keen to leave behind in his teens.

“I went very early to Madrid,” he says. “I had just finished the upper school. I was a minor. I had a big argument with my family – the only one that I remember – telling them that I was going to Madrid and I was not going to do what they expected to do. They found me work in the bank in the place where we were living, and I went away from that.”

Indeed, Almodovar says, he soon forgot about childhood, all the good and bad of it, for years. “I was very positive and the bad things of that period I forgot completely. I never thought about that.”

He had too much to be getting on with. After General Franco’s death in 1975, Madrid went on a hedonistic binge. La Movida, it was called. The counterculture had arrived in the city with a vengeance. Drugs, gay sex. Suddenly, everything went. And Almodovar was at the heart of it.

By day he held down an office job for the telephone company. By night he was writing comic strips, performing in fringe theatre, singing in a punk band and shooting Super 8mm movies. Eventually he made a scrappy, wilfully outrageous film, Pepi Luci, Bom and Other Girls Like Mom and his film career had begun (he kept the job at the telephone company for years though).

In 1988 his breakthrough film Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown picked up an Oscar and “Almodovarian” began to be a verb. At that point it was shorthand for camp melodrama, garish bad taste and a willingness to shock (in 1989’s Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! Almodovar manages to make a sweet love story out of a narrative that involves a former mental patient kidnapping a B-movie star).

At the end of the 1990s a new, more mature (and, yes, possibly more bourgeois) Almodovar began to emerge, culminating with All About My Mother, a film about maternal grief, and the troubling, emotive Talk To Her, possibly his greatest film, which takes in bullfighting, women in comas, abuse, Pina Bausch and Caetano Veloso.

And somewhere in the years that followed, Almodovar started to think about his childhood again. It had, he admits, taken a while. “Even in my movies I didn’t think about my childhood until I was more than 50.”

He did so in two films he made back to back, Bad Education in 2004 and Volver two years later.

“The first time that I really go back and see my childhood as the origin of fiction was in Bad Education when I was thinking about sexual harassment in school which was incredibly common in the Catholic college. And for some reason I was old enough to look back. In Bad Education I put the worst of my memories and immediately with Volver I included the more joyful part.”

The joyful part in question was the women he grew up surrounded by. It’s why women are so central to his movies, he says. “They would be the origin of so many of the feminine characters I would write later. I had a bad memory of the village, but I extracted from those bad memories things that were so positive for me; the women of the street where I lived, and my mother.”

Pain and Glory taps into those women too, but it’s also a film about 1970s and 1980s Pedro and life during La Movida. That world and the love affairs of that time are Pain and Glory’s lost paradise.

I have to ask, I say, what does he think the Almodovar of those years would make of the man he has become? “I’m not sure he would be happy that his future would be this one,” he says, laughing.

“I feel very close to that person and I would live the same way again with the good and the bad that came from that.

“The Pedro of the early eighties would never think he’d become an internationally known director. Not even in his wildest dreams. So, I was very lucky.”

Pain and glory. That’s Pedro Almodovar’s own story. In life and in cinema.

Pain and Glory is in cinemas from Friday.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here