Over black and white footage of an old silent movie, a woman begins to speak. “Most films have been directed by men,” she says in a calm and measured voice. “Most of the recognised so-called movie classics were directed by men.

“But for 13 decades and on all six film-making continents, thousands of women have been directing films, too, some of the best films.”

She ends with a series of questions – “What movies did they make? What techniques did they use? What can we learn about cinema from them?” – and a proposal: “Let’s look at film again through the eyes of the world’s women directors. Let’s go on a new road movie through cinema.”

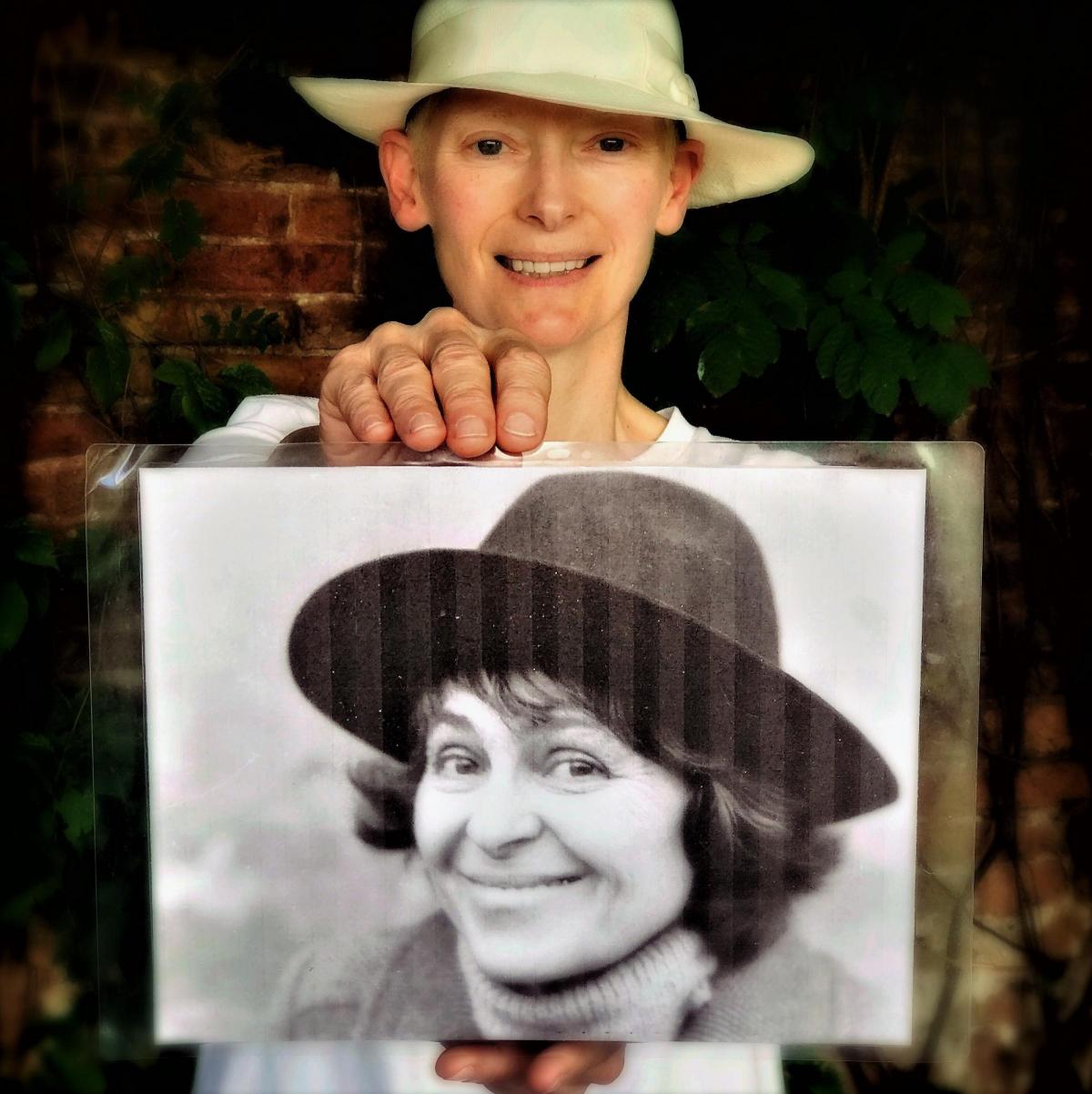

The narrator is Tilda Swinton and the footage is the opening sequence of Women Make Film, a new, 14-hour documentary written and directed by Edinburgh-based film-maker Mark Cousins. Released on Monday, it does pretty much what it says on the tin – tells you how people make films and why, and what they put in them that makes us feel happy, sad, scared or uplifted – but it does it using clips culled entirely from the work of some of the best of those thousands of women film-makers.

There are plenty well-known names among the scores of women whose work Cousins features. Sofia Coppola, Oscar winner Kathryn Bigelow and Jane Campion are there. Modern British directors are well represented too, among them Lynne Ramsay, Clio Barnard, Andrea Arnold and Joanna Hogg. Meanwhile cinephiles and fans of European cinema will recognise the names of Chantal Akerman, Claire Denis and Agnès Varda, a pioneer of the French New Wave.

There’s room, too, for women better known for their time spent in front of the camera, such as Angelina Jolie, or for following other pursuits entirely, such as singer Beyoncé Knowles and artist-musician Laurie Anderson.

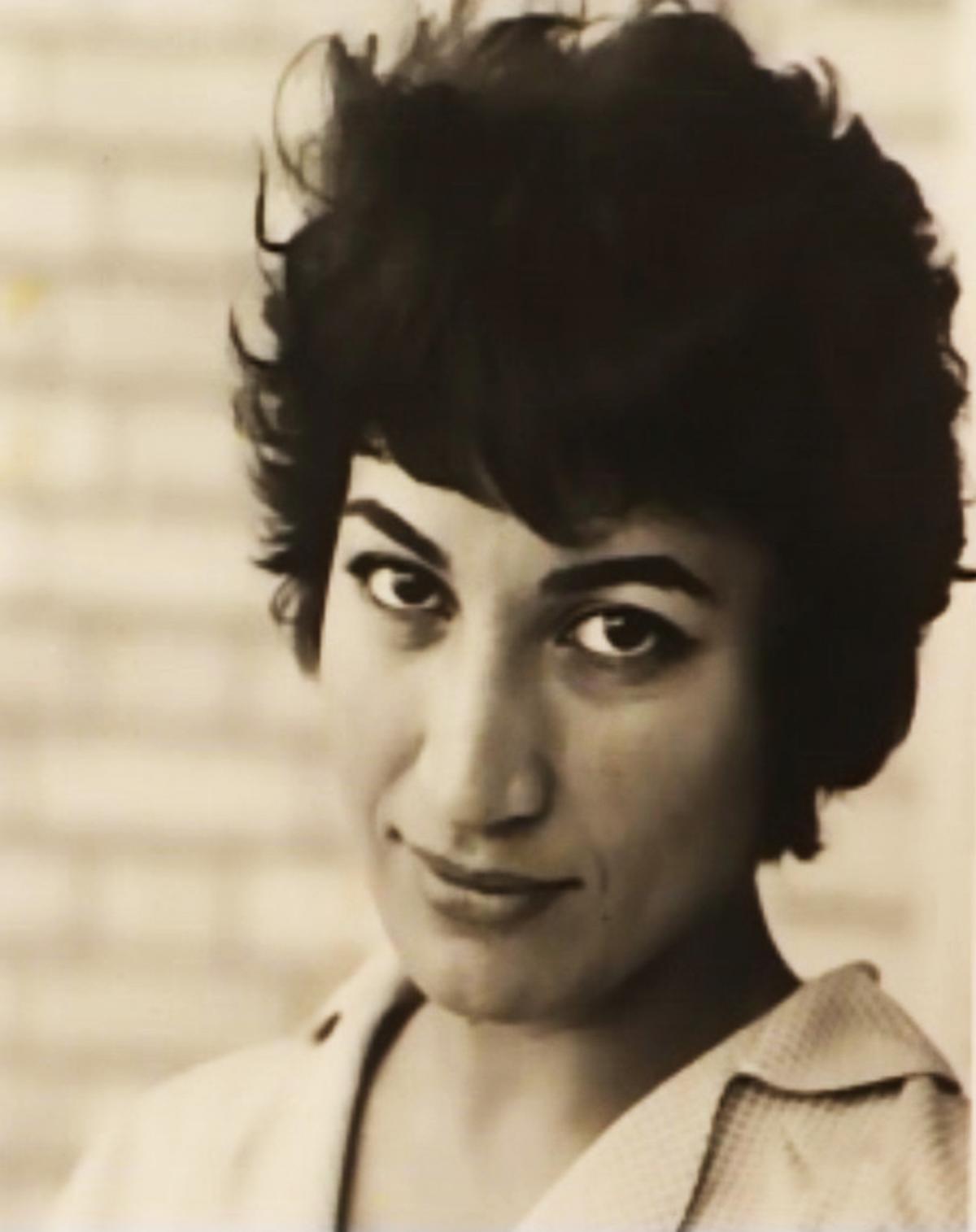

But also in that roster of names are some women you’ll never have heard of, such as pioneering Soviet director Olga Preobrazhenskaya, who shot silent film Women Of Ryazan in 1927, Jacqueline Audry, who made the original French version of Gigi and later collaborated with Jean-Paul Sartre, Polish film-maker Wanda Jakubowska, who returned to the concentration camp in which she had been imprisoned – Auschwitz – to shoot The Last Stage in 1947, or Forough Farrokhzad, a pipe-smoking Iranian feminist who died in a mysterious car crash in 1967 aged just 32.

For Cousins, the project has been a long time brewing and is a companion piece of sorts to The Story Of Film, his 15-part series which aired on More4 in 2011.

“Probably for decades now I’ve been asking the basic question in any part of the world and in any genre: ‘Who are the great female film directors’?” he explains. “I just felt as if I had a pressure cooker in my head which was building and building with more films that I’d seen and loved and so the idea was therefore to make another big, massive project full of great film clips.”

He wanted, he says, “to try and force the conversation off the same male auteurs that everybody talks about all the time”. Men, presumably, like Stanley Kubrick, Ingmar Bergman, Federico Fellini and Orson Welles, whose Citizen Kane used regularly to be voted the best film ever made.

Women Make Film features 183 directors in all and contains clips from around 400 films. The oldest featured is from Alice Guy-Blache’s 1907 film Course à la Saucisse and among the most recent is one from Patty Jenkins’s 2017 superhero blockbuster, Wonder Woman. Cousins doesn’t much like to talk about stand-outs or favourites, however.

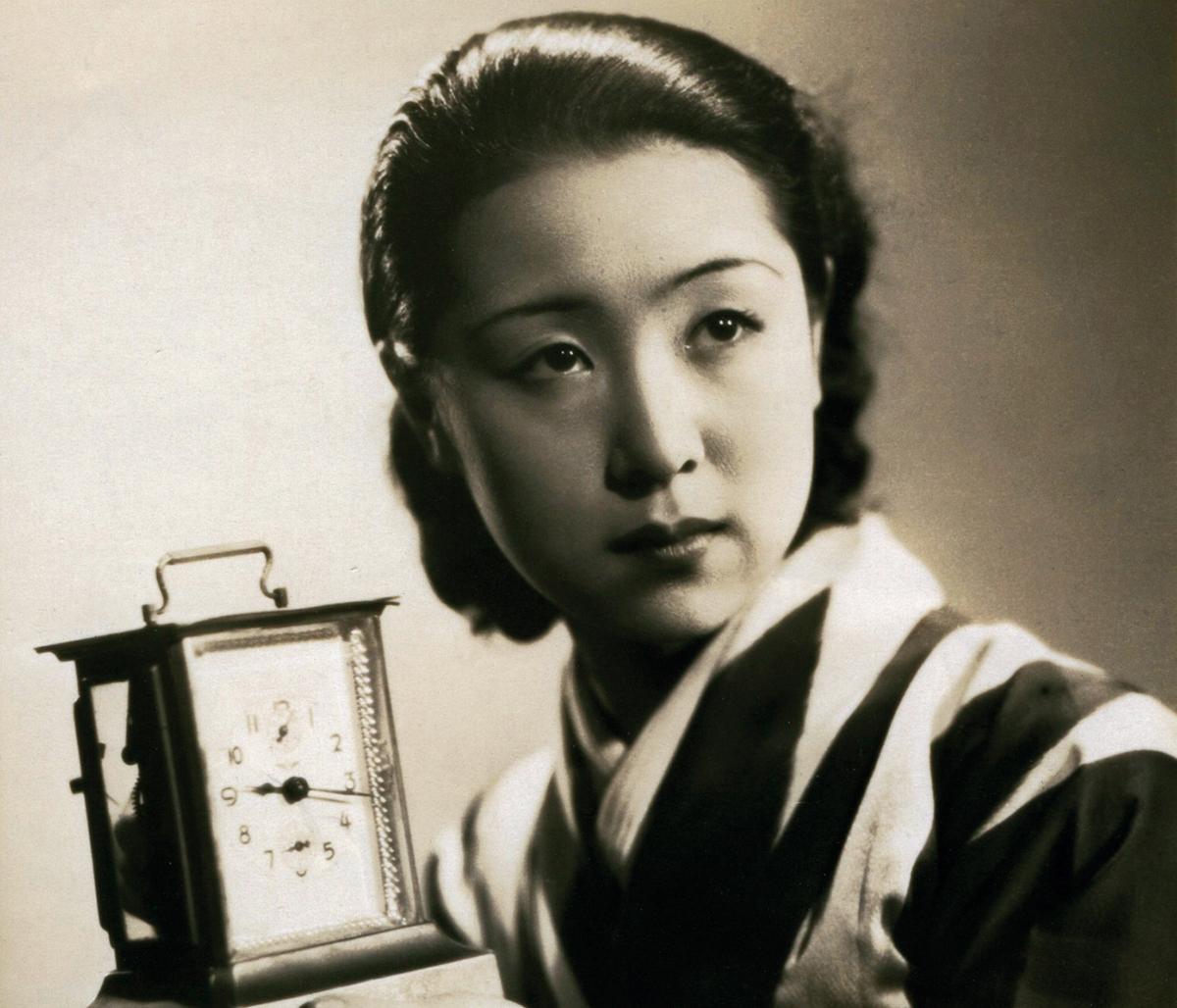

“There’s something like 10,000 women who have directed films and I’ve chosen 183 so I think I’ve already chosen the highlights,” he says. But when pushed he’ll name a handful. Kinuyo Tanaka, for instance, who was a famous actress in Japan before she turned to directing; Sumitra Peries, known as “The Poetess of Sinhala Cinema” and later the Sri Lankan ambassador to France; and Franco-Bosnian Lucile Hadžihalilović, sometime partner-in-crime with Argentine bad boy Gaspar Noé. “And of course Agnès Varda, who thank God people are now talking about”.

But he does make special mention of Binka Zhelyazkova, the first Bulgarian woman to direct a film. “Her work challenges so much of what we think we know about cinema.”

He adds: “A lot of people think when they’re approaching Women Make Film that it’ll be quite obscure directors and people have used words like obscure to me. But a third of the population of her country saw Binka Zhelyazkova’s work so she was far from obscure. We’re not talking about marginal figures or experimental artists who are working on the edge of the system.”

Although many female film-makers are concerned with “the female gaze”, most are not, so Cousins is also setting out to challenge the notion that women tend to make certain types of films.

“The old idea, especially on the right, was that women are very good at themes like empathy, or they made films about children or relationships,” he says.

“But the more you look at films directed by women around the world and in all periods, none of those generalisations apply. Some of the best war movies have been made by women, some of the best film noirs and road movies have been made by women.”

Intercut with the clips is the thread that binds Women Make Film together: footage showing a driver’s eye view of roads being travelled in Scotland, America, Europe, everywhere Cousins and his camera have travelled, hypnotic interludes which, after 840 minutes, bring the viewer to an appropriate final destination. And although it’s Swinton’s voice we hear in the film’s opening chapters, she isn’t the only narrator.

“Once Tilda’s on board that gives something a real stamp of credibility,” says Cousins. “For me, people know that when Tilda Swinton is involved in a project it’s not going to be facile about gender, it’s not going to indulge in black and white stereotypes and that was crucial. She brings all the cultural heft that comes with Tilda Swinton and it helps when you’re talking to other creative collaborators or people in the business world that she is voicing and executive producing.”

She also opens doors. As a result, Cousins was also able to enlist the help of fellow actresses Thandie Newton, Kerry Fox, Debra Winger, Adjoa Andoh, Sharmila Tagore and Hollywood legend Jane Fonda as co-narrators.

“One of the great things about working with Tilda Swinton or Jane Fonda or Kerry Fox or Debra Winger, all these women that I worked with on the voiceover for this film, is that they all believe passionately that these generalisations about what men or women are like are harmful. One of the reasons they all got involved in this project was because the film doesn’t generalise about what men and women are like in real life or behind the camera.”

Women Make Film premiered at the Toronto Film Festival last year and also screened at the Glasgow Film Festival. Was Cousins ever challenged about why a man was making a film about female directors?

“Yes, quite a few times, as you can imagine,” he admits. “I knew that would come but I always knew this was a film about cinema. It’s not in any way trying to say women are like this or women are like that. The only thing it says about women directors is that they’re very, very good. It’s about cinema and the complexity of cinema.

“What happens is that when people see the film, whatever concerns they have about me being a male director seem to disappear. People think this will be a chronology, that it will be about the film industry, the female gaze, victimisation of women or sexism but it has none of those things.”

However, sexism does exist and, despite the #MeToo movement, the victimisation of women in the film industry (and others) does persist. Cousins had been at work on Women Make Film for several years when the Harvey Weinstein scandal broke. How did the revelations about his behaviour and the subsequent societal fall-out affect the project?

“We watched with horror but no surprise,” he says. “I didn’t know that Harvey Weinstein was a sex abuser but I knew the industry was sexist. We were editing at that point and I have to say, although we read the papers every day, in the end we didn’t change anything because [the film] wasn’t intended to be about the industry, or it wasn’t intended to be about marginalisation. There was a dawning realisation as we were editing throughout that period that if we had been telling a story about marginalisation then there was the potential to re-victimise these directors who had tough times making these films. It we had talked too much about that toughness rather than talking about their work, that would have tainted them.”

At the end of the day, he thinks, it’s the work that matters. The best thing he or anyone else can do is shine a light on it. Yes, let’s change the film world,” he says. “But let’s know what the great women have done.”

Women Make Film: A New Road Movie Through Cinema is released on Monday on Blu-ray (BFI). It will also be available to stream in five weekly episodes via the online BFI Player.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here