Part One: “And the beat of my heart marks the passing of time …”

THESE days Dave Ball, the other one in Soft Cell, is 61 years old, and living with synths and keyboards and a heart condition in south-east London. As he has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, he is having to shield himself in these pandemic days.

“I’ve not been to a supermarket for about 10 weeks, which I don’t miss. The corner shop is more expensive, but my health is more important, I think, than risking getting this bloody virus.”

It is now more than 40 years since Ball first met Marc Almond on his first day at Leeds Polytechnic in 1977. Four years later the duo would be number one in 17 countries with their synthpop cover of Tainted Love.

Both events are covered, among many, many others, in his new memoir Electronic Boy. “It’s the usual rags to riches and destruction,” he says, summing up the book’s narrative. “I come from humble beginnings. I’ve always been quite a humble person, but I’ve had an interesting life. I’ve always been catholic in my tastes.”

Well indeed. He’s worked with both Genesis P Orridge and Kylie Minogue, after all (not at the same time, mind).

“I think all sorts of music and art are valid. I’m not very judgemental about that. There’s good really leftfield music and there’s great pop music and I’m very much into pop art, I’ve always been a massive Warhol fan and that’s always been my thing. Andy Warhol started off as a commercial artist but also was very subversive in his other work and with the Velvet Underground. That always inspired me immensely.”

Soft Cell managed to be both leftfield and pop, driven by Ball’s synth lines and Almond’s naked emotionalism. There is a danger from the distance of nearly 40 years that we forget how big the duo were, that we write them off as one-hit wonders because of the ubiquity of Tainted Love and overlook the fact that they had another handful of top 10 hits, as well as inspiring obsessive devotion among their fans.

They were loved and hated in equal measure, I think it’s fair to say. Almond, kohl-eyed, braceleted, in particular.

“A lot of people hated Marc. ‘Who’s this little bloody poof,’ you know,” Ball admits. “And then they thought I was the boyfriend who looks like Freddie Mercury. I think they thought ‘weird gay blokes.’

“The BBC liked us as a novelty act even though we were the second-biggest selling singles band in 1982 in the UK. But there was something about us that disturbed people whereas Boy George had a more trans look than Marc, but he was kind of cuddly. There was something about us. I think we were just a bit too dangerous for them. I’m proud of that. I wanted to be dangerous. That’s why we used to hang out with Throbbing Gristle.

“How could these two weird perverted art students be top of the charts? It annoyed people, which is the best thing for teenage rebellion to do isn’t it?”

Read More: Pet Shop Boy Neil Tennant

Read More: Scotland's best singers

Ball’s own onstage demeanour was detached for the most part, idling in neutral in comparison to Almond’s full-blooded commitment. But he loved pop and wanted the duo to be big. “There was a desire to be successful,” he admits.

When it came, though, with Tainted Love, it was unexpected, disorientating and in its own way, expensive.

“It took everyone by surprise. One of the biggest career mistakes of Marc’s and my career was we didn’t write the B side. Back in the day when you had vinyl singles with an A side and a B side, if you’d written the B side you got 50 per cent of the publishing. And no one, including our manager our publisher and our record company, said you should write your own B side. Because they didn’t think it was going to be a big hit.

“So, we did Where Did Our Love Go which, artistically, worked beautifully on the 12 inch. We’d taken it into Where Did Our Love Go with the lovely Lancaster Bomber descending sound, as I call it, as a segue in the middle, this big, droney thing.

“And then we stupidly put that on the B side of the seven inch. And so, Holland-Dozier-Holland and Ed Cobb made a fortune. That record has sold God knows how many millions.”

Part Two: “Sometimes I feel I’ve got to run away.”

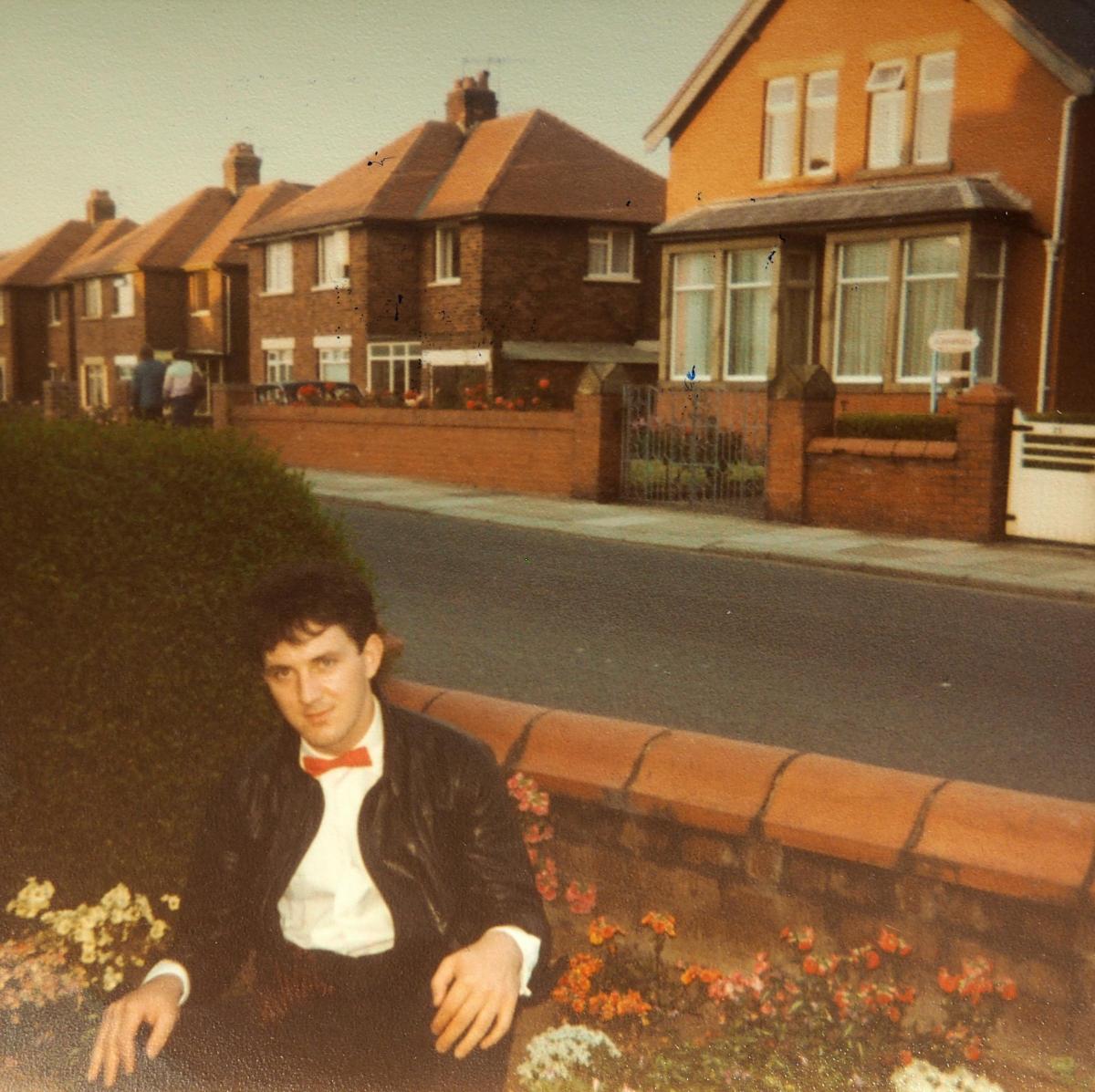

Dave Ball grew up in Blackpool with a disciplinarian father and the knowledge that he was adopted. He still thinks fondly of Blackpool at least. “It was a great place to grow up. At that time, it was a big influence. All the funfairs and the craziness and the entertainment industry. There was always a showbizzy thing there. That rubbed off on me a lot. I found that quite exciting.”

His father had an influence too. He was, Ball says, “very authoritarian, but he was also an engineer. A crucial thing. That’s what got me interested in electronics.”

There were more negatives than positives in that relationship, though. And it left its mark.

“Initially, I was quite repressed. I was quite sexually repressed. It wasn’t until he died that I had my first full-on sexual experience. I was terrified of him really. I didn’t really like him that much. I think he always resented the fact that I wasn’t his own son. I was much closer to my mum. I think there was a resentment that my mum couldn’t have his kids. He would have much preferred to have his own offspring. He liked my sister more than he liked me. There was always some resentment there.

“When he died, I thought, ‘Right he’s gone now.’ And with the money he left me I bought my first guitar, realised I wasn’t good enough playing it and traded it in for my first synthesiser.

Who was the teenage Dave Ball who went to Leeds Poly? Someone eager to start again, it seems.

“I had this horrible year of my dad dying of cancer. My poor mum caring for him, and him in agony, taking stronger and stronger medication until he was admitted to hospital. And when he died, I couldn’t stand being in that house with my mum who was becoming more and more alcoholic and my sister … We just didn’t talk to each other. It was a horrible atmosphere.

“And I always had aspirations for art school anyway. I was just desperate to get away and start creating my own life. It was just very tragic. I just needed to escape really. It was a turbulent time, a very emotional period of life.”

When he got to Leeds, he gravitated towards Almond straight away. “He was the most interesting looking person. Everyone was wearing brand new Wrangler’s and Levi’s denim and Doc Martens and then there was this guy with bleached hair and a leopard skin top, like the one my mum wore, and spandex trousers. I thought, ‘He must be in the fine art department. Let’s go and have a word with him.’

“And I’m not gay, but there was something about Marc. He is a very attractive man, he’s a very handsome guy in his own way. He had a look about him. I saw him and I thought, ‘He’s a star.’ I thought ‘One day I’m going to get him – not in the bedroom – but I’m going to get him to do my music with me.’

“And it happened. He just looked like a pop star. The moment I saw him I thought, ‘He looks like someone famous already,’ which, obviously, he now is.”

Even then, Almond’s look caused consternation. Looking back, how brave must he have been? Especially in Leeds at that point, Ball says.

“There was a serious National Front presence in Leeds. People were scared. There were a lot of skinheads. Marc and I used to sit in this coffee shop in the Merrion Centre. It had a mezzanine. We’d go there because it had a record shop. We used to sit upstairs by the balcony and watch, and there would be about 200 Leeds United skinheads wearing black bomber jackets all doing Nazi salutes, marching through the Merrion Centre.

“We were terrified and fascinated by it. They came to our gigs, but luckily the leader came up and said, ‘We really like your band.’ Thank God for that!

“Leeds was very scary at that time. The Yorkshire Ripper as well. It was a very strange time in Leeds, very heavy. A serial killer and a bunch of Nazis wandering around at night.”

Ball and Almond lived in the same block of flats opposite each other. Almond would play either Donna Summer or Siouxsie and the Banshees. That conflation of punk and disco would become a default setting for Soft Cell

“With Tainted Love I think Marc heard it in the Warehouse disco and he liked that lyric. Soul diva with electronics. Apart from Kraftwerk, Giorgio Moroder was a big influence. Marc was obviously destined to be a male diva. It was that mixture of machines with the passionate voice. He was really into Scott Walker as well, and Gene Pitney. He was into the sixties soully, ballady thing and I was into machine music, and the two things found a new formula. Giorgio Moroder had beaten us to it, but we were definitely in the zone.”

Success then took them to New York. Soon they were hanging out in Danceteria (“our favourite”), the Mudd Club, Paradise Garage and Studio 54 and inviting their drug dealer to appear on their single Torch.

“We just loved it. It was a party. You’re young and rich ... And we suddenly were. We were young and famous, and we suddenly had a bit of money in our pockets. It was the best place to be.

“But there’s the excess of New York once we got into the drug scene. That’s where we got into the darker stuff. We were taking on darker American influences because we were quite naïve when we were doing the first album. That was based on London. That was based on our experience of living in Leeds in ‘glamour and squalor,’ as Marc used to say.”

New York was a place of excess. And that would have an impact. “It ended up in a downward spiral by the third album, I think.”

Part Three: “I’m skilled at the art of falling apart.”

In the book, Ball writes candidly that, by the age of 24, he was a father and a drug addict. The band was beginning to fall apart and so was he.

“It was tearing me apart. The worst thing in the world, I found, was the innocence of children. You know you’re on drugs and you think no one knows, and a little kid four or five years old … They don’t even know what drugs are, but they just give you this look, and it just makes you feel so guilty. They know. ‘What’s the matter with daddy?’ It’s the most horrible look. It makes you feel so guilty. That was probably the worst experience. I was still high on something, whether it was acid or coke, and they just look at you. Oh my God. I couldn’t look at them.”

Soft Cell split in 1984 and it would take Ball years to clean himself up. “I went through a wilderness period,” Ball admits. Eventually, though, he met Richard Norris and they formed dance outfit The Grid in the late eighties, which led to Ball returning to the top 10 with Swamp Thing in 1994.

In that time Ball also co-wrote Kylie’s 1997 single Breathe and worked on an ambient EP with Billie Ray Martin. “We had a good stream of chart success and did loads of remixes for everybody. Yeah it was a very fruitful period for me, that.”

Part Four: Say hello and wave goodbye

In the years since there have been reunions with Almond for another Soft Cell album, Cruelty Without Beauty, in 2001, and reunion gigs, including 2018’s farewell gig. But there is also new music. And now the book. Writing it has, he admits, been cathartic.

“I thought it would be quite good to write a book when I was 50. I’m now 61, so I was 10 years out there. It took a while.”

What’s obvious is that Ball is not the man he was. He’s better than that, he hopes. “I still like a drink, but I haven’t even smoked for nine years and I certainly don’t do drugs anymore. All my drugs are prescribed now. You don’t really get a buzz off inhalers and steroids, to be quite honest.”

Electronic Boy: My Life In and Out of Soft Cell by Dave Ball is published by Omnibus Press, £20.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel