WITHOUT Freddie Burretti would there have been a David Bowie? That’s today’s question.

Bowie’s long slog towards stardom through the 1960s finally came to fruition when he became Ziggy Stardust. And as Bowie himself once said, it was Freddie Burretti who was “the ultimate co-shaper of the Ziggy look.”

An erstwhile model, Burretti was a member of early Bowie band, Arnold Corns. But it was his abilities with a sewing machine that would really help shape pop’s future. Burretti was responsible for many of Bowie’s stage costumes for Ziggy.

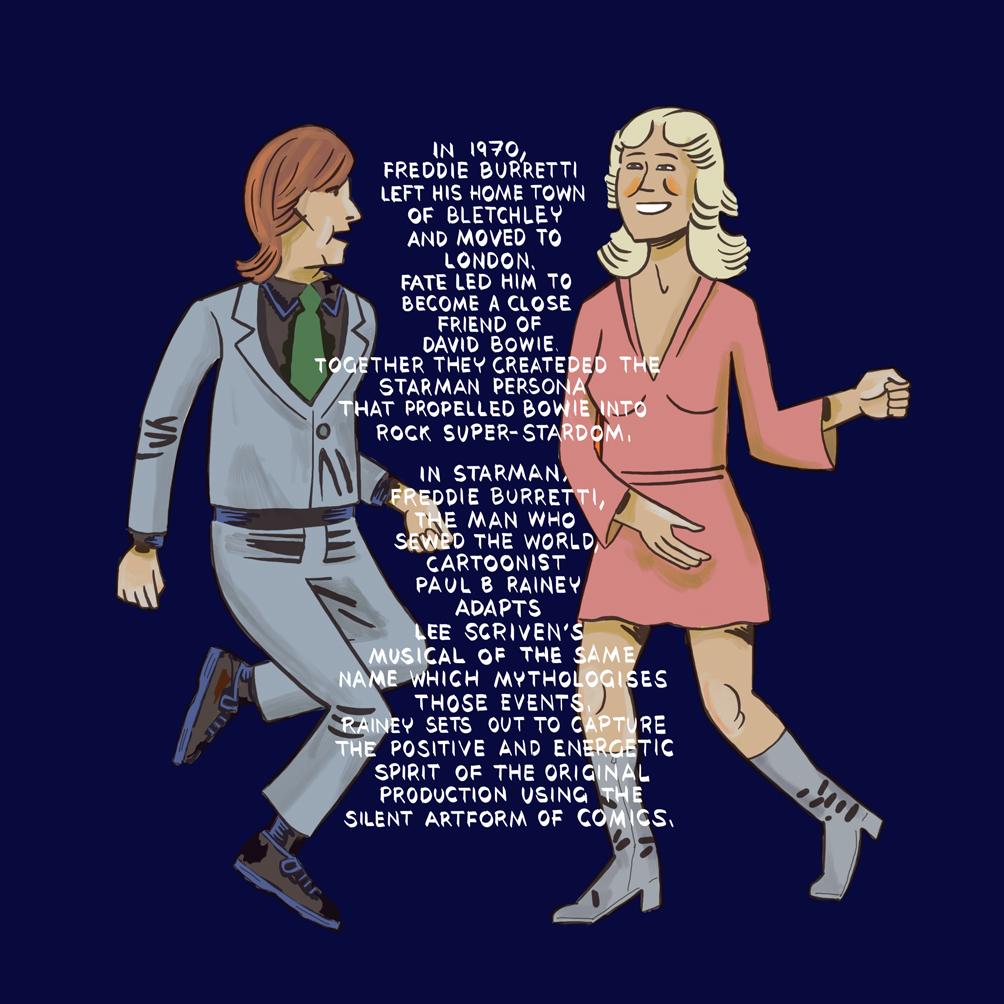

In new graphic novel Starman, cartoonist Paul Rainey retells Buretti’s back story and his relationship with Bowie. The result is the quintessential glam rock story; council estate kids who put glitter on their face and reinvent themselves.

Here, Rainey, best known for his work for Viz and his graphic novel There’s No Time Like the Present, talks to Graphic Content about pop music, Milton Keynes and Bowie as a Marvel character.

Paul, Starman began as a musical. What sparked you to reinvent it as a graphic novel? And what was the challenge of it?

I produced some artwork for Lee Scriven, who wrote the musical, early on in the process, which was about a couple of years before Bowie died. Lee told me about Freddie Burretti, who lived in Bletchley during the late sixties before moving to London, meeting David Bowie and co-creating Ziggy Stardust with him. The original appeal for Lee was Freddie’s association with our hometown (we are both long-time residents of Milton Keynes), but he very quickly built a story around real events that I always thought was very good. After the production was performed over three nights in Milton Keynes about 18 months ago, Lee suggested to me that the story would make a good comic-book and I suddenly realised that I really wanted to draw it. Prior to that, I had always thought of it as Lee’s story.

What was your own interest in Freddie Burretti? And why does he matter in the Bowie story?

Freddie helped David Bowie to create his Ziggy Stardust character, which is the persona that rocketed Bowie into rock superstardom. I’ll be honest, prior to Lee drawing my attention to him, I was unaware of Freddie’s existence. The appeal for me has always been the mythologised version of real events in Lee’s story; the journey from working-class Bletchley, a place I know very well, to a glamourous otherworld which usually feels impossible to access.

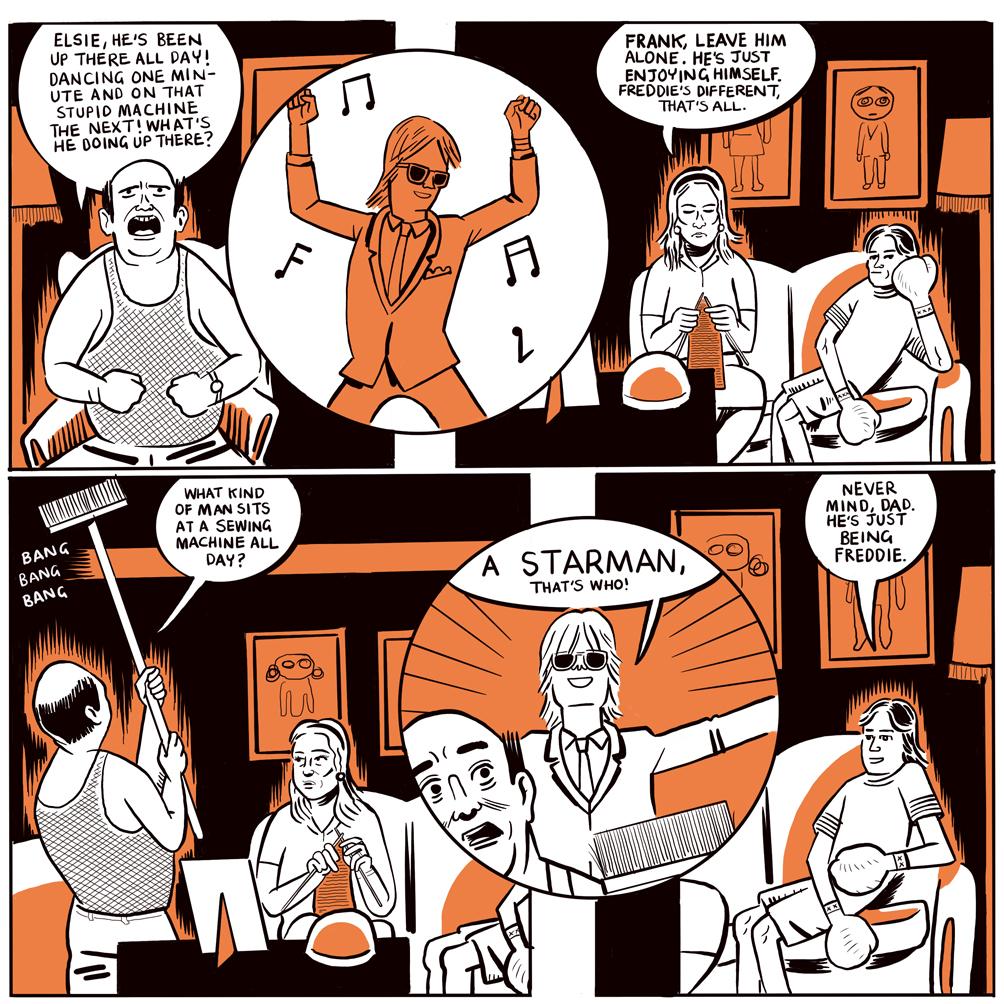

The fun of Starman is the contrast between the glamour of the pop star and the council house reality of life in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Was that part of the appeal?

Yes, very much so. Both Lee and I have lived in Milton Keynes for decades and, although neither of us has a desire to leave, we understand the contrast between the reality of everyday life for most, earning money to pay the bills, and where we would like to be, which for Freddie is an imagined place that can accommodate his Starman. It’s also always good to be reminded that it isn’t really too long ago that being a young, gay, working-class man was far more difficult than it is today in this country.

Pop has always been a vehicle for gay identity and that is very much part of this story. What do you think pop offered at this point in our social history?

I always think of the British cultural response to gay people during this period was usually juvenile. I imagine if you were young and gay then, it must have been especially difficult. So, an artist like Bowie standing up and saying publicly that they were bisexual must have felt like a revelation. Lee always says that he imagines that Freddie had a role to play in Bowie making that announcement.

There have been several Bowie-related graphic novels in recent years. Why does he appeal to graphic novelists?

I think it’s because Bowie often looked like he was a character who had been created by Jack Kirby or Steve Ditko, the artists who created all those hit Marvel superheroes during the 1960s. I imagine, guys who grew up to become professional comic artists practised as children by drawing Doctor Strange, The X-Men and Ziggy Stardust.

Read More: Nejib on his Bowie graphic novel Haddon Hall

What is your own relationship with Bowie?

On the spectrum of Bowie fans, one being ‘I like David Bowie’ and ten being ‘I’m an absolute fanatic’, I think I probably sit around the two or three positions. All my favourite pop bands from my formative years are undoubtedly influenced by him; Soft Cell, The Human League, Depeche Mode and, later, Suede. There’s a photograph I occasionally see float around social media of David Bowie reading an issue of Viz. As an occasional contributor, the idea that he has seen some of my comic work is very appealing to me.

Why comics?

This is a difficult question to answer because it suggests that making comics is a choice I’ve made or that I could just as easily work in another artform, which I don’t think I can. I enjoy telling stories and I enjoy drawing but the advantages that comics have over other forms of expression is its affordability -you just need a pencil and sheet of paper - and immediacy - you can react artistically to a real event more quickly.

What is your history as a reader and a creator?

I got into comics during the 1970s when I discovered UK reprints of Marvel Comics and British adventure weeklies like Action, Battle and 2000 AD. It’s been a constant journey of discovery ever since. I’ve been into zine-making and self-publishing my own comics since the 1980s. In 2015, Escape Books published my graphic novel, There’s No Time Like the Present. I’m also an occasional contributor to Viz.

Who are your cartooning heroes and heroines?

There are far too many to credit but, whenever I am asked this question, I always mention John Wagner, who is the writer who created Judge Dredd, Mike McMahon, who is a 2000 AD artist from the 1970s and 1980s, the original Escape Magazine crew, cartoonists like Eddie Campbell and Phil Elliot, and Alan Moore, obvs.

What’s next?

I’m currently drawing the final episodes of my years-in-the-making comic-strip, Why Don’t you Love Me. I think of it as a sitcom about a dysfunctional family who, at the end of the day, still don’t love each other. I took a break from it to draw Starman, but now I’m back and hurtling towards the conclusion. Why Don’t You Love Me currently appears in David Lloyd’s online comic, ACES Weekly. I also post an old episode to my social media every Sunday morning.

For more information on Paul’s work and to purchase a copy of Starman, visit pbrainey.com

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here