FROM Metropolis to Mega City-One and MR X’s Radiant City, comics and architecture have a long shared history. The comic book is an urban form, one that grew with the expansion of cities in the late 19th and 20th centuries.

The urban landscape is a key component in everything from Marvel superhero stories to Japanese anime. And in recent years architects and urban planners themselves – in the shape of Charlotte Malterre-Barthes and Zosia Dzierzawska's Eileen Gray: A House Under the Sun and Christin Pierre’s Robert Moses: Master Builder - have become the subject of graphic novels.

Perhaps this shouldn’t come as a surprise. Historically, both architects and cartoonists are interested in rendering three-dimensional forms in two dimensions.

Perhaps that is less of a concern for architects in these days of computer modelling. But cartoonists are still exploring urban forms on the page.

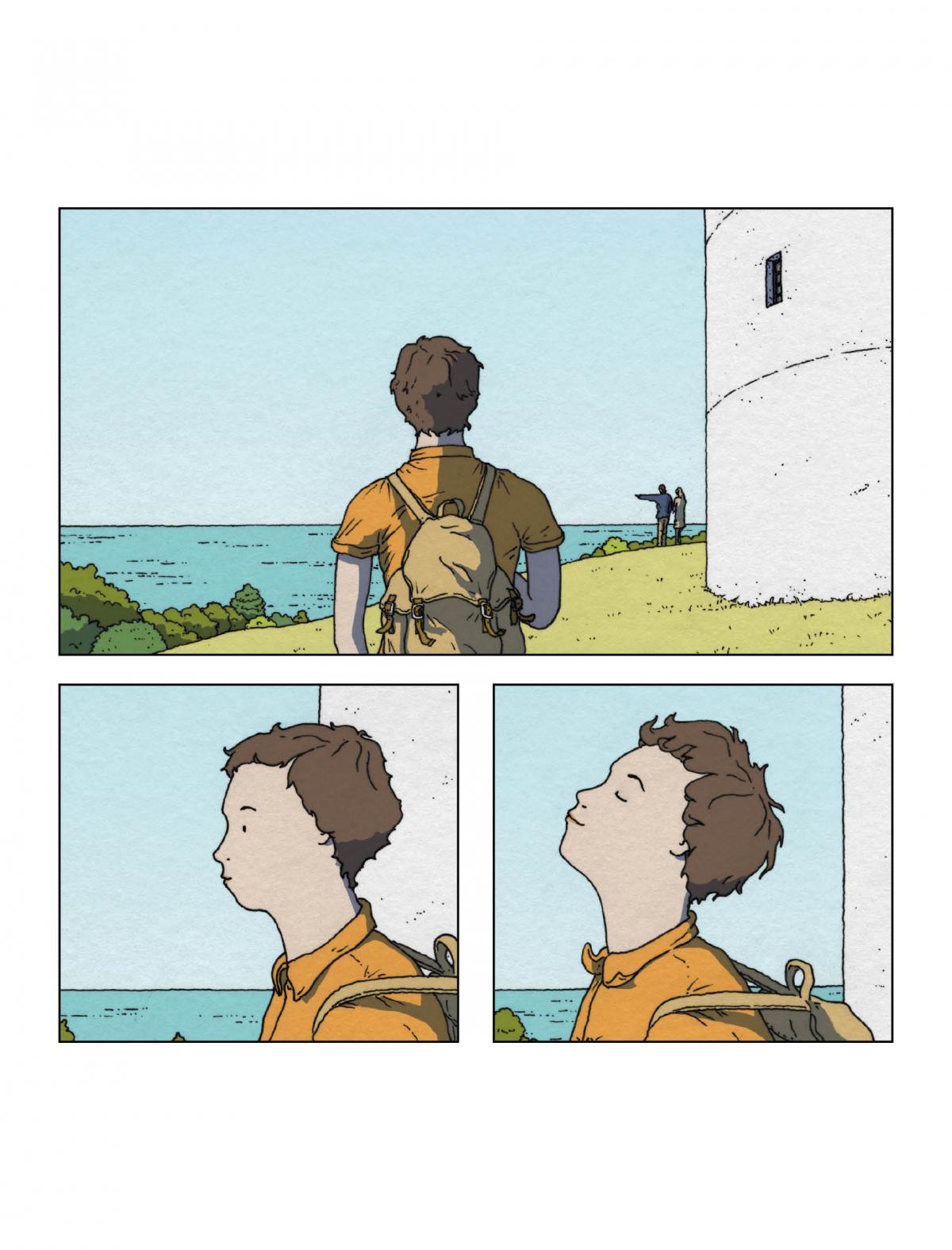

One of the most delightful is Victory Point, the new graphic novel from cartoonist and illustrator Owen D Pomery.

Victory Point is a seaside town designed in a 1930s modernist style, all whitewashed walls and clean lines. Inevitably, this being Britain which has a rather problematic relationship with modernist architecture, the plan wasn’t fully realised. Even so, Victory Point attracts architectural tourists to see it. But what about those people who live there?

Ellen grew up in the town and at the start of Victory Point is returning to visit her father, explore her past and try to find some clarity on what she should do in the future. Oh, and fit in skinny-dipping.

What follows is a quiet, yet potent exploration of place and personality. Pomery, who trained as an architect and who has already published the graphic novel British Ice this year, paces the story out in large, beautifully coloured panels that allow the reader to fully explore the world he has created.

It’s a lush vision. Reading Victory Point I was thinking how much would one of these modernist properties go for in the current market? And could I afford it?

Here, Pomery talks to Graphic Content about Victory Point, his favourite comic book city and which architect would make the best cartoonist.

What was the origin of Victory Point?

I guess it was mainly reaching a point in my life, both generally and artistically, of reflection. Taking stock of what had gone before, what had panned out and what hadn’t, and wondering what direction I would head in going forward. The origin of Victory Point is in that moment of pause.

What did you want to explore in the story?

The idea that impermanence is a kind of permanence. That everything is constantly moving and in a different state of flux. Many narratives, ideals, initiatives and philosophies are generally skewed towards achieving an ultimate goal, and this felt increasingly less the case in my own experience. I don’t think it’s uncommon to experience things more in shades of grey as life goes by, but it still feels pretty underrepresented in the landscape of stories. We all seem programmed to want everything to come to a conclusion. Without getting too heavy early on, the only real conclusion is death.

Ellen is at something of a crossroads. Is that something you recognise?

Yeah, definitely. But at the same time, it’s not as dramatic as all that, and that’s kind of the point. The stakes in Ellen’s life (and mine) aren’t that high, but if you’re a person with a constantly questioning mind, who is always somewhat dissatisfied with life, you have to somehow come to peace with that. I certainly don’t feel like I’ve achieved it, but I recognise it more and more in me.

You studied architecture and that’s very evident in Victory Point. How do you think that background changes how you approach comics?

In lots of ways, some of which are banal and subconscious, but others are far more visually evident. I’m probably even more fascinated by buildings and peoples’ relationship with space than when I worked purely in architecture and it’s exciting to get to explore that in a different medium. Probably the most interesting effect (to me, anyway), is that my approach to narrative and story design is sort of the inverse of my architectural design process. Put simply, when designing a space, I think of all the “stories” that will play out there and try to design something that will hopefully meet those needs. By comparison, my writing process is to start with an image or a thought (in this case a modernist seaside town) and then explore why it has come to exist, who would be there, and why.

And why comics in the first place? What do they offer you that illustration can’t?

I love illustration, and the restriction of creating a single image is challenge I very much enjoy. That said, it’s so much more to me than a purely visual composition. I can’t help but speculate on where that person I’ve just drawn walks off to when the scene un-freezes, or what do I see if I turn around and look the other way? So, I really like getting to explore that in much more detail, creating a richer and more complex narrative and world.

Comics and architecture, discuss?

There is a whole book’s worth of an answer and one I won’t even attempt to summarise here. But the relationship between the two is a fascinating subject, whether it’s the representation, the theoretical intent or something else completely. I’ve certainly enjoyed working in both and particularly the observations I’ve made looking back over the fence at the other discipline.

What’s your favourite comic book city?

Probably the nameless city in The Arrival by Shaun Tan. It’s an incredible wordless graphic novel that explains the immigrant experience by putting the main character in a fantastical cityscape but populated with very human and relatable elements. Everything is alien, yet on some level, very familiar, and I love it when works of art can talk about universal truths, by focusing on apparently minute details.

When was the last time you went skinny-dipping?

Hah. I think it would have to be a couple of years ago now, while attending a friend’s wedding on an island in Croatia. I stayed for a few extra days and spent my time exploring the coast, reading, sketching and swimming. When you find a deserted, paradisiacal cove, what else are you going to do?

This is your second graphic novel this year. That’s showing off, Owen.

Not my intention I’m afraid. Publishing is an odd business, and despite the fact I finished British Ice almost two years ago and Victory Point wrapped only about two months back, they both ended up landing in the same year. So, it’s far more coincidence than productivity, but I don’t mind it, as the books are very different in tone and are with two separate publishers, so I think they complement each other in a way. Whether I would have chosen them to come out in a year of global pandemic is another question, that only time will answer. It’s been lovely seeing people treating themselves to some escapist reading in these times, but obviously bookshops, and everyone else, will struggle going forward.

What influences feed into your comic work (I see everything from Herge to Julian Opie in there).

Thank you. Yes, there’s definitely a lot of Herge, Rutu Modan, Moebius and other comic influences in there. But I think the pool of things that interest me is pretty wide. Artists like Hopper and Wyeth, the photography of Saul Leiter for example, and filmmakers like Sergio Leone and Michael Mann … It’s all in the mix somewhere. I could go on forever, as there are so many books, works of architecture and even music I could add too, but it’s often hard to put your finger on them as a direct comparison. I think everyone is influenced by so much more than just those working in the same field, it’s just more difficult to spot and articulate.

What’s next?

I’m genuinely not sure. I’ve got a few projects that I’m tinkering with, but I’m resisting the temptation to dive right into something longform. I think it’s important to use the gaps between things to experiment and work out what it really worth pursuing, so I’m attempting to do that. In terms of comics, it’s a sad reality that despite having two books out, with two reputable publishers, I definitely can't make a living from it, so my other paid illustration work always has to take priority. Luckily, I very much enjoy being an illustrator too, and I've been doing more concept work recently, which has been a new experience.

Which architect could have made a great graphic novelist?

I would go for Ray and Charles Eames. The range of designs and mediums they worked in show the breadth of their artistic and curious minds, which I think is key for storytelling. Their interrogation of subjects and I’m sure, each other, would mean something interesting would undoubtedly come out of the process.

Victory Point by Owen D Pomery is published by Avery Hill

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here