THE tamarind tree has gone now, the one that stood in her grandmother's garden in Karachi. When Sumayya Usmani was growing up, she'd spend hours in its shade, lounging on the cool earth and occasionally sampling the tree's fruit.

Its flesh, she remembers, was ugly and pulpy but intoxicating. It was the fruit's distinctive umami quality – the fifth, "savoury" taste, after salt, sweet, sour and bitter – that would grow to inspire much of her Pakistani cooking.

That cuisine has now found its way into Usmani's first book, a memoir-come-cookbook, fittingly entitled Summers Under The Tamarind Tree. It's an elegant, colourful, evocative carousel of meat and non-meat dishes, vibrant street food, seafood, poultry, homegrown guavas, spices and epic celebration feasts. Not only does it turn the spotlight on a cuisine largely unfamiliar to most of us, but it also reminds you that the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, the world's sixth-most populous nation, deserves to be known for its formidable appetite for food and entertaining, and not simply for, say, its long war against the Taliban.

"There were a couple of main reasons why I did the book," says Karachi-born Usmani, now 43, sitting in the kitchen of her Glasgow home. She moved here last summer in search of a better-quality and more affordable life than could be found in London, her original destination after leaving Pakistan.

“One was that I grew up in Pakistan and had great memories. Every time I looked back on them, they always involved food. When I moved to the UK 10 years ago, the first thing that struck me was that there was no real appreciation of the food of the country. It did not have its own voice. I found that quite strange, considering that the UK is a very big, spice-loving country. The sub-continent’s food was all labelled as one. There were so many niche or regional cuisines of different parts of the continent coming up, but no-one ever spoke about Pakistan.

“It led me to think that either people confused Pakistan's cuisine with other cuisines, or they thought it was all the same. Or maybe they were just not interested in it, because of the negativity that came out of the country. I don’t know. Maybe they were thinking of the political situation there: that’s a natural thing, it happens in every country that has political strife.

“But, having had such a wonderful childhood in Pakistan, I felt it was time to highlight the positivity of my country. Food is such an integral part of our culture. People might think, ‘Well, every culture likes food’, but Pakistan, although there are tons of things to do there, has a comparatively limited means of entertainment, due to many political and religious reasons. But food has never been an issue. It is always the biggest entertainment for people. Food is in our psyche. We love to feed others, to entertain, to give out food to the poor – that’s a huge part of our culture. All the festivities are centred on food, too.”

It’s interesting to learn that, at lunchtime in Pakistan, businesses shut so that the employees can eat together, seated around a "dastarkhan", a dining cloth spread on the floor. The contrast with Scotland could not be more pronounced: here, the order of the day is a shop-bought sandwich at the desk. Street stalls in Usmani’s native land are hugely popular, with vendors shouting (the better to be heard above the incessant noise of traffic) the prices of their fruit or vegetables. Food stalls do a booming trade in pakoras, samosas and biryanis.

In Pakistan you can have meals delivered to your house by a waiter from a roadside or takeaway restaurant at 3am. And when it comes to entertaining, Pakistan does this in style, whether it’s an Eid feast or a wedding celebration. Usmani remembers that many wedding guests contrived to arrive exactly at the moment the food was served, thus avoiding the rituals. The food would be served at midnight and people would pounce at it “like hungry cats”. Where many cultures see food as mere sustenance, Usmani says now (her own cat nestling on her lap), that back where she came from, it’s something much more central to life. Every single aspect of creating a meal is something to be rejoiced in.

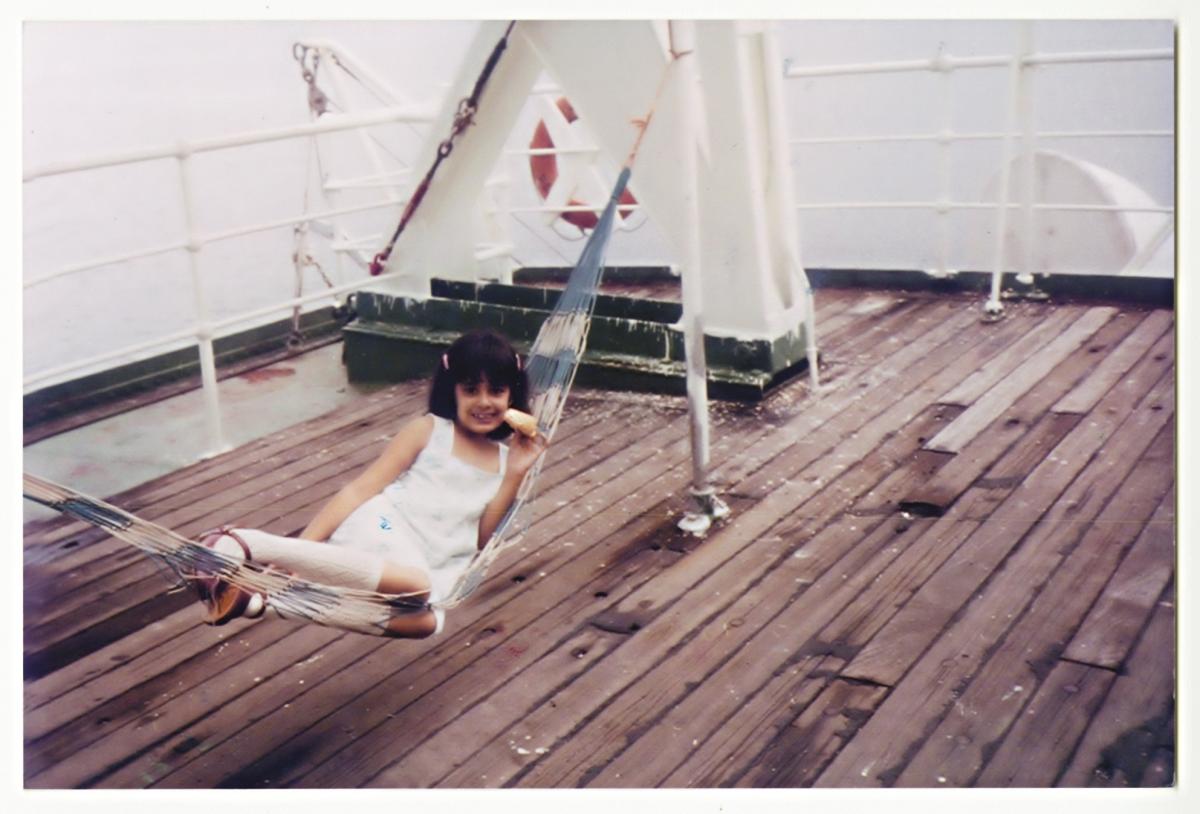

Usmani actually spent much of her childhood at sea, on cargo ships captained by her father. Their many destinations included Europe, Japan and the Ivory Coast. Her mother would cook on board, seemingly non-stop. Usmani’s passion for the the ocean – and for food and cooking – began here. She remembers catching the flying fish that leapt onto the ship’s lower deck; she would cover them in salt and crushed red chillies, then flash-fry them.

Later in life she worked in shipping legislation in Pakistan along with her father, before spending more than a decade as a lawyer. When she moved to London, it was as a shipping finance lawyer. Yet she never really had an abiding passion for the law; what motivated her was writing about food, and sharing recipes. As a pastime she began a blog, which took on a life of its own, and eventually she began writing for food magazines.

“I found myself in the law firm, writing recipes,” she says. “Really, that was a wake-up call that it was time to maybe make a choice.” She happened to work with Madhur Jaffrey on her TV show and cookbook ("she’s a fantastically inspirational lady, the guru of south Asian cookery”). Usmani shared with Jaffrey her idea to write a Pakistani cookbook, reasoning that it was important to continue her culinary heritage. Jaffrey agreed. Five years ago, Usmani finally quit the law and began collecting recipes. She’s delighted with the resultant book, which describes as a "treasure", and is now writing a follow-up. Her decision to leave behind a secure, well-paid job has been vindicated.

Do Pakistani families in the UK maintain that communal attitude towards food? “I think they do," she says. "A lot of Pakistani immigrants came either from the Kashmir or Punjab regions … [which both have] a very rich Pakistani food culture, and a lot of them have upheld many traditions. It’s harder with the second- and third-generation, of course, but the beauty of food, of heritage cuisine, is that it links you to your homeland and gives you a very strong sense of identity, no matter where you are in the world.

“My seven-year-old daughter, Ayaana Jamil, is growing up here. She may not know much Urdu in the long run, she may not speak it as frequently or as fluently as I do, but one thing she will be able to carry on is her heritage cuisine.” Ayaana has patiently watched her mother cooking and writing, and has been helping her to slice tomatoes and to roll koftas.

How might Scotland have benefited from the sharing, joyous attitude that Pakistani people have towards food. “That’s a very good question,” she says. “Obviously, I’m fairly new to Scotland, and this is just an observation.” She notes that there seems to be very little identity to modern English food: it’s all mixed up, especially in the huge melting-pot that is London. “I’ve realised, researching Scottish food, that some recipes in medieval times were incredibly interesting, involving saffron and peppercorns. I marvelled at that.

“And then I looked at Scottish food today, at the fact that nobody actually realises that you have some incredible recipes. And not just old-fashioned or medieval ones, but contemporary ones. I mean, people laugh at the idea of stovies, or haggis, but they’re such an incredibly rich bond with history, traditions, with invasions that happened to this country. Scotland has absorbed so much from its conquerors and its immigrant populations, and Scottish food has evolved in such an interesting way. Stovies, for example, has a French influence in its name: rich food that is simple to cook and is made from leftover meat and potatoes. I love it. People are not giving enough love to that sort of thing; it is, after all, a beautiful heritage that they must preserve.

“Everyone,” she adds, “has got into fast food. Horrible deep-fried things; burgers and stuff. I wonder, why are you eating all of this when you could be eating your seasonal foods and really hearty food that is very cheap to prepare and which goes such a long way? Scotland has some great national dishes and an incredible national larder – in that context, you guys are blessed. And that’s why I try to use it in all my recipes.”

She admits to sometimes giving Ayaana chicken nuggets for the sake of convenience; but the widespread indigenous habit of relying on fast food or defrosted pizzas, say, comes from “the fear of cooking well – I think people believe it’s expensive to create good food, or it takes too much time. No, it doesn’t”.

She’s happy to be a member of the local convivium (or chapter) of the Slow Food movement – a global organisation founded in Italy in 1989 and which, to quote from its website, links the pleasure of food with a commitment to community and the environment. “I joined because I thought it would be nice to give my angle of eating that way, in which everything is made from scratch. I mean,” she concedes, “there are still a lot of burger and fried-chicken places in Pakistan, and of course there’s a huge street-food culture over there – everyone just goes and get kebabs or rotis. But the culture of cooking at home remains very strong.

“I’d like to bring that knowledge to Slow Food Glasgow. It’s nice to be able to say that [Pakistan is] a poor, Third World country, but even the poor people who can’t afford expensive ingredients will eat vegetables, or the staples, rice and bread. I remember people in villages, where there was very little to eat, and there was no meat, would eat a roti [unleavened corn bread] with pickle, and that would be a meal. They’d make up a fresh pickle – it makes my mouth water just thinking about it – and would make a big roti and just dip it into the pickle, and have it with daal. It’s about just getting back to the basics. It’s not about having money: it’s about taking the time for your family.”

She adores Glasgow but admits to the occasional bout of homesickness. Her parents still live in Pakistan and she flies home once or twice a year. She is also planning to visit northern Pakistan this year to research her next book.

Sadly, she says, her grandmother’s house was pulled down several years ago. As for the tamarind tree, “it doesn’t exist any more: it’s heartbreaking”. But the memory of the tree, and its pulpy flesh, and her thousands of other memories of spices, and family meals, and celebration feasts – all of these are utterly indelible.

Summers Under the Tamarind Tree: Recipes & Memories From Pakistan by Sumayya Usmani is published by Frances Lincoln, £20. The author will sign copies at Waterstones Sauchiehall Street, Glasgow, at 6.30pm on May 12. Websites: http://sumayyausmani.com; www.mytamarindkitchen.com

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here