It is the big unexplored paradox at the heart of Scotland's public life.

We have - or so we keep being told - a Nordic-style egalitarian political consensus that favours greater equality of both income and wealth.

But Scotland also has an Anglo-Saxon-style neoliberal economy producing a dramatic gulf between the very rich and the very poor.

Now two of the country's leading economists have looking at how Scottish authorities - with both the powers they already have and those they are likely to get under further devolution - can resolve this paradox.

Stirling University's David Bell and David Eiser, both fellows of the Centre on Constitutional Change, conducted the research on behalf of the David Hume Institute.

Their findings? That successive governments since Margaret Thatcher have seen inequality in Scotland soar. And that classical models for measuring inequality are failing to register some of huge moves at the two extremes of wealth and poverty north of the border.

<

<

Prof Bell and Mr Eiser reckon the Scottish Government already has some ability to mitigate against inequality.

In fact, Scotland is already, using standard measures, less unequal than the rest of the UK.

The academics said: "At first glance it might appear that the Scottish Government has little in its power to address income inequality.

"It doesn't have powers to regulate the labour market. So it doesn't control the minimum wage, or legislation around insecure work such as zero-hours contracts and agency working.

"It can't regulate the finance industry (source of much of the rise in wage inequality at the top); and most taxes and benefits remain under Westminster control."

But there are things Scotland can do - if it has the political will - and there are things it is about to be able to do, thanks to new devolution of income tax and, potentially, the minimum wage.

Their work comes as The Herald renews its reshaping Scotland series of articles on how the country's public sector can adapt to survive austerity.

Property Tax

Scotland already has the power to tax land and property. But its existing system is neither fair nor effective, say Prof Bell and Mr Eiser. The SNP has frozen the council tax since it came to power in 2007 after failing to introduce a local income tax. Bell and Eiser regard this tax as "regressive", since high value properties are charged at a lower percentage than low-value ones. Worse, their research has uncovered huge regional differences in the tax.

So a typical Band D council tax payment in Aberdeenshire is little more than half of one per cent of the median house price. In East Ayrshire a Band D council tax bill jumps to more than 1.3 per cent of the median house price. Council tax is not an effective way of taxing wealth.

This system creates a bias in favour of home ownership, the economists warn, embedding intergenerational housing and wealth inequalities.

The experts said: "There is thus a strong case for reforming council tax with a proportional tax on property or land value, possibly combined with some form of tax on the capital gain that owner occupiers benefit from. The case for such reform has been made many times previously, but is clearly a difficult political sell."

Income Tax

First Minister Nicola Sturgeon and her cabinet will soon have substantial powers over income tax. That could mean the SNP imposing progressive taxation to match its progressive rhetoric.

They could put the top rate of tax - for those earning more than £150,000 a year - up from the current 45 per cent to 50 per cent.

That won't have a huge impact on headline inequality measures, Prof Bell and Mr Eiser reckons. After all, roughly only one Scot in 300 pays the top rate. Conservatives and others warn this move could disincentivise entrepreneurs and innovators. Prof Bell and Mr Eiser are not so sure. "Existing evidence is inconclusive on how significant this effect might be," they said.

Progressive tax policy, however, could come as part of a wider campaign of what Prof Bell and Mr Eiser called "moral suasion".

They said: "The Scottish Government already playing a strong role here in relation to promoting the living wage.

"But the notion of moral suasion can extend to promoting good employment and pay-setting proposals more widely.

"Many people dramatically underestimate the extent of inequality because they are not aware of existing pay structures. Encouraging firms to publish pay-ratios, and involving worker representatives on remuneration committees could both help to mitigate 'within-firm' inequality."

Minimum Wage

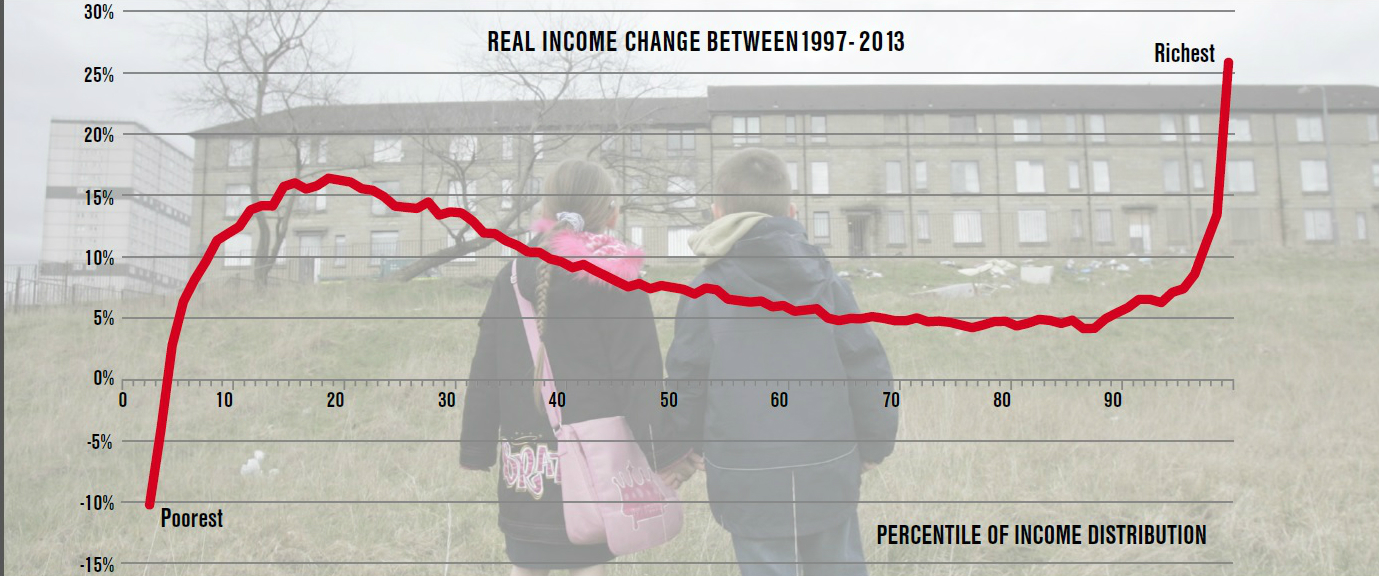

The very poorest are now 10 per cent power in real terms than they were when Tony Blair became prime minister in 1997. Everybody else is better off with the very rich seeing their incomes leap 25 per cent.

But - aside from millionaires - the people who had done best since New Labour are those who rank among the ten to thirty percentiles, the poor, rather than the very poor. Their incomes, in real terms, have gone up as much as 15 per cent. The reason: minimum wage and tax credits.

The SNP has called for this minimum wage to be devolved.

So has Labour's potential London Mayoral candidate Tessa Jowell. Mr Eiser has some sympathy with these calls. He said: "There is a good case for devolving the minimum wage within the UK."

His logic: many entry-level minimum wage jobs are in sectors such as care and retail where they simply can't be moved.

So putting the figure up in one part of the UK shouldn't see too many jobs migrate to another.

Mr Eiser reckons Scotland could raise its minimum wage to around 60 per cent of its median wage without a detrimental effect. That takes it from £6.50 to £7 an hour.

But the economist stressed a minimum wage hike was "not a panacea for addressing in-work poverty".

He said: "It needs to go hand-in-hand with a wider strategy for addressing low pay, including aspects of employment law which are currently reserved to Westminster."

Crucially, a higher minimum wage could save Westminster on tax credits it gives to the low paid. Would the UK exchequer pass on that gain?

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article