CHRISTMAS ANGEL

By Alan Spence

And so this is Christmas, and what have you done?

A good question.

The soundtrack in the cafe is on a loop, its relentless Christmas playlist endlessly recycling, one song after another with not even jingles or tired banter in between.

Another year over, a new one just begun.

Segue from that into Jingle Bell Rock, and I saw Mommy kissing Santa Claus, and God help us, Mistletoe and Wine.

Christmas past.

You want a Christmas story, so I’m here with my laptop and my cappuccino, ready to roll.

The memory is there, just at the edge of my awareness, and right at this moment it feels important to bring it back, relive it, write it down. It’s something that happened decades ago, when I was a child.

You know that way when you’re filling in a form online, maybe buying travel tickets, and you have to enter your details. And for your date of birth, you click on and scroll down, year by year, back through the decades, flashing past, so fast, all the years you’ve lived, back to when you were born. And it hits you, visceral, you think God, where did it go?

A lifetime.

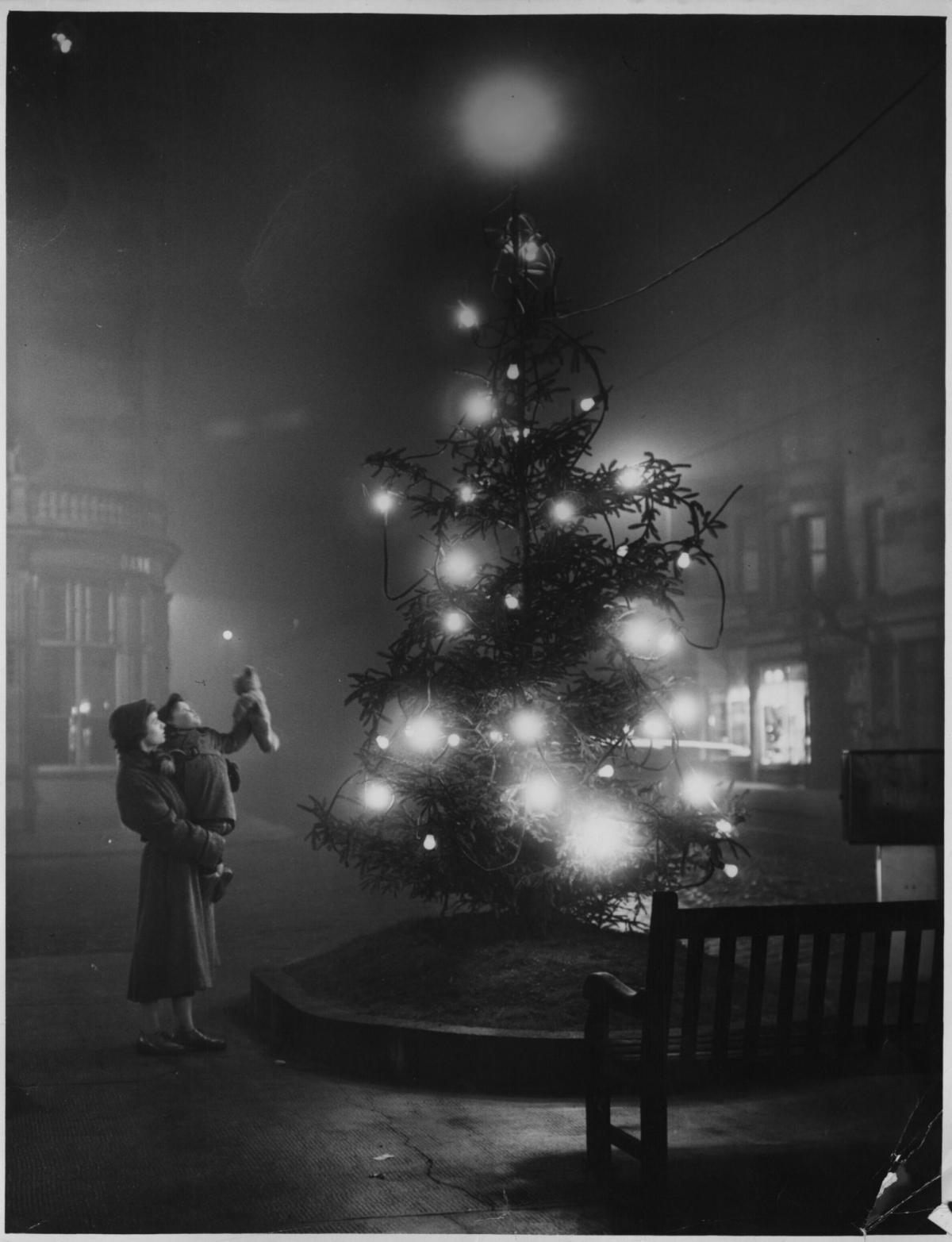

So I’m scrolling back to the early 1950s.

I must have been six or seven, a wee baby-boomer in grey postwar Glasgow, a time of shortages and rationing, making do. In the winter, to keep warm, I slept at the foot of the set-in bed in the kitchen, between my parents’ feet, facing the opposite way. But this night, before Christmas, I couldn’t sleep at all, because of what had happened earlier, because of what I’d heard.

The radio had been on, the wireless, crackling away in the corner, programmes my parents liked – Scottish Country Dance Music, Semprini Serenade. Semprini had an intro he gave every week, over his theme tune. Old ones, new ones, loved ones, neglected ones… It washed over me, a background. But at some point the music must have stopped, been replaced by voices, a discussion, two men arguing. I wasn’t paying attention, but then one of the voices was suddenly raised, dismissive, making a point.

That’s as ridiculous as believing in Father Christmas.

I felt a coldness in my stomach, asked my parents if it was true what the man had said, that there was no Santa.

They made light of it. Och son, they said. Och.

They’d been meaning to tell me, when they thought I was old enough. And maybe now I’d found out, maybe yes, I was old enough.

I’d wondered once or twice, heard older boys talking at school. But I hadn’t believed it, because that would have meant my parents had lied to me. And it didn’t make sense. If there wasn’t a Santa, where did the presents come from?

One of the boys had laughed at me.

Your ma and da buy them, ya daftie.

And that really made no sense. Presents were expensive - a toy garage, a cowboy suit, a football. There was no way my parents could afford those. Money was tight. There was no extra, nothing to spare.

I asked them and they said they managed, they put a wee bit aside, it wasn’t much. I felt an ache inside, a pang, at the thought of it. One of them must have gone to a toyshop, bought the presents in secret, hidden them away, brought them out and wrapped them for me to find on Christmas morning. The milk and digestive biscuits left out for Santa would be gone, and that was proof that he’d been. Santa would even have washed the glass and saucer, left them in the sink.

I was amazed that they’d gone to all the trouble, played the game.

For a moment I thought I was going to cry, but my father said, There you are then, now you know.

I looked round the room, the same old room where we lived, the same but not the same. There was the table with its red formica top, the plates and cups, my father’s ash tray full of stubbed-out fag-ends. There was the kitchen cabinet with its glass doors. In one corner was the cooker, in the other the bed recess. In the grate the fire burned low. The same old room but I was seeing it differently, the light sad and tired.

What else is made up? I asked. What about God? Is he not real? What about Jesus?

My father looked at my mother, cleared his throat, rubbed his stubble.

My mother said, Of course they’re real. Of course they are. And she ruffled my hair and laughed, but her eyes were sad.

I’d once tried to ask my father about something that troubled me. I was looking at the little blue chair I always sat in, beside the fire. And I wondered if my parents saw it the same way. What if they saw it as green, or red, and that was what they called blue? And what if they saw it as something different altogether, not a chair but something else?

My father didn’t understand.

I tried again. How do we know? How do we know we see the same things?

Beats me, said my father.

How do we even know what we see is really there?

My father laughed, rapped with his knuckles on the wooden chair.

Feels real enough to me!

I used to teach students to do this, to get them kick-started, writing from their own experience.

Begin at the top of the page with I remember…. See where that leads.

I’d quote Rilke at them. He told a young poet to rescue himself from general themes, write about what his everyday life had to offer. When you express yourself, he said, use the objects around you, the images from your dreams, the things you remember.

I felt as if I hadn’t slept at all, had just lain awake turning and thrashing this way and that. Once or twice my mother shooshed, told me to hush, go to sleep. My father snored, snorted, grunted, growled like some great scary animal in the dark.

I shut my eyes tight, opened them again, wide, and held them open as long as I could. That made colours behind my eyes, flashing. I looked out at the shapes and shadows in the room, the slightest lightening of the darkness in the grey square that was the window, catching a faint light from the other tenements opposite.

I tried to focus on something up near the ceiling, realised it was the washing, hung up, draped over the pulley to dry. That must be my father’s shirt, the long tail, the sleeves spread out, and beside it, smaller, my mother’s blouse, and next to that, my own t-shirt, a couple of dishtowels. That made sense of the objects, resolved them into things I recognised, familiar. But once or twice I looked up and the shapes, white, seemed to shift into something else, something strange, something I could almost but not quite see. It was unsettling, there but not there.

How do we know what we see is really there?

My father snored.

There was no Santa, they said, but God and Jesus were real. And what about angels? I hadn’t asked that. But they had to be. If God and Jesus were real, then angels were too.

And that was it, right there. All at once it was clear. I saw, I understood.

Those pale shapes, wings outspread, were an angel. The Christmas Angel. If you looked too closely, peered into the dark, you’d just see the washing on the line. But if you looked sideways, out the corner of your eye, you might just catch a glimpse. You could feel it, letting you know it was there.

So even if they didn’t know it was happening, your parents and everybody else were touched by the angel passing through. That was how it worked. That was why there was still Christmas.

The certainty of it comes back to me. I remember it, vivid and clear, the intensity of the awakening, the realisation. It was something given, vouchsafed to the child I was.

So here it is, Merry Christmas, everybody’s having fun.

And I wish it could be Christmas every day.

The soundtrack keeps pounding and jangling along. And in amongst it there’s a Japanese melody, all tinkly synth. A mistake maybe, something that slipped in. Then I recognise it as Ryuichi Sakamoto, the theme from Merry Christmas Mister Lawrence.

The first time I visited Japan, back in the eighties, I was surprised to find they celebrated Christmas. I should have known they’d embrace it - another opportunity for a frenzy of gift-giving, explosion of kitsch. But sometimes they got the iconography spectacularly, surreally wrong.

I was in Kyoto, passing one of the big department stores, and the glittering window display caught my eye, all neon dazzle, flashing coloured lights. And at the heart of it was a figure of Santa, arms outstretched, on a cross.

Ho Ho Ho.

Thank God for absurdity.

There are TV screens in the cafe, high up on each wall. The sound is turned off, and silent news coverage flickers, with a running commentary underneath. If it catches your eye it’s impossible to look away, impossible not to read the constant stream of headline, quotation, analysis. The text is obviously predictive, always catching up with itself, correcting itself.

I look up and Prince Charles is on screen, making a pronouncement on something or other.

Speaking as an Asian… the text reads.

What?

After a beat or two it’s rewritten.

Speaking as a nation…

The images on the screen keep changing, with or without the running text underneath.

The Glasgow bin lorry crash this time last year, six dead. The Christmas lights turned off in George Square. And the year before that, the Clutha Bar disaster, still unexplained. Close-up of wreckage. Floral tributes on the wet pavement.

George Clooney in Edinburgh, at a charity food shop, helping the homeless. Feed the world. Cameras flashing, folk taking selfies on their phones.

The royal couple and the royal baby. Prince Charles again, speaking as an Asian.

Je suis Charlie.

Hajj stampede in Mecca. Earthquake in Nepal. Those thousands and thousands of migrants, desperate to reach Europe. So many, so many.

Logos, VW and FIFA. Scandal and corruption. Blatter’s heart attack. Athletics doping expose. The Olympic rings. Trump blustering. Build a wall. Nuclear deal agreed with Iran.

Russian jet crash. Hundreds gunned down in Paris. C’est la guerre. Air attacks on Syria. Fingers on triggers, on buttons.

It’s Christmas.

War is over, if you want it.

Let them know it’s Christmas time.

That searing image of the wee boy washed up on the shore, face down at the water’s edge. Wee guy in his trousers and red t-shirt, his trainers. His trainers for godsake.

The brutal cartoon that used the image, juxtaposed it with Ronald McDonald grotesque in his clownsuit, advertising a 2-for-1 meal deal for kids, and the caption So close to his goal.

A couple of tables away there’s a small boy with his mother - he’s maybe seven or eight - and they’re just sitting down. She’s making space, placing the tray with her coffee, his fizzy drink, and he’s lost in his game, eyes on the handset, firing off salvo after salvo, each one followed by a blast he mimics, making explosion-noises in the back of his throat.

Yes! he shouts after every kill. He punches the air. Yes!

He stops for a moment, swigs his drink.

You know what? he says. These guys I’m killing are actually very cool.

I’m sure they are, says his mother, almost interested. Very cool indeed. She takes another sip of her flat white, squeezes the boy’s shoulder. He grins up at her, then he’s concentrating again, back in the game, taking out more and more very cool guys, blasting them to oblivion.

An old friend of mine, a poet, died earlier in the year, and she’d chosen the songs for her own funeral, so we all filed out of the crematorium to Abba singing I have a dream.

I believe in angels…

And whether we did or not, we walked out of there grateful, lifted up into a better part of ourselves.

My mother only lived a few more years past that Christmas, didn’t live to be forty. My father survived her (that’s the word they use) for twenty years more, just made it into his sixties.

Those decades again, scrolling past, accelerating.

Here’s to the future now, it’s only just begun.

My father would have been 100 years old this year, my mother would have been 95. Unimaginable. They were never going to make it.

What would they have made of this - me sitting here in a cafe with my laptop, trying to shape a memory into a story?

I’m back there sometimes in dreams - that time, that place, my first few years on the planet, the monochrome Fifties. Or for no reason at all there’s a flashback, the exact taste and smell of how it was.

I thought I was done with writing about it, obsessively picking it over. But here it is - Merry Christmas! - surfacing again, and it feels as if it matters.

The-child-I-was, coming to himself, aware of his own story, his own consciousness.

I never told my parents what I’d seen, what I’d felt. I didn’t have the words to explain in any way they’d understand. I’d made my own sense of it, seen something profound about shifting levels of reality, about different kinds of truth. I’d seen through the veil.

The Christmas Angel. Washing on the line.

As I write this I’m seeing them so clearly, this young couple, struggling. The war they’d lived through was so recent, just a few years. They’d survived, were trying to make a life. They’d lost two sons before I was born, one after the other, died within days of being born.

By miracle or grace I made it, I lived. The boy.

So much I didn’t know, and still don’t. Their lives.

Once in a while - a blue moon - they’d manage to go out dancing. I had a photo of them, lost long ago, in clothes they must have rented or borrowed, a formal suit, a sparkly dress. The dancing. In the photo their eyes shone.

I have this image in my head, like a scene from a black-and-white film, and it’s my mother cutting my father’s nails. He had worked in the yards and had big broad hands, a workman’s hands. He could cut and sew canvas, tarpaulins, but he couldn’t cut the fingernails on his right hand. He couldn’t manoeuvre the scissors with his left, it was too finicky and awkward. So my mother did it for him. I remember the scissors as huge and blunt, blackened with age, and they made a squeaking noise. They were the same ones we used for cutting string, or paper, or bacon rind. My father’s big hands, my mother’s smaller, the manky old scissors, the sheer physicality and tenderness of it.

The other day in a charity shop I saw a book called Angels: An Endangered Species.

Believe in angels? If only.

The Angel of Mons. They said it appeared over the battlefield, in between the two opposing armies. Soldiers from both sides saw it. Reports from the front line.

I read an article somewhere - probably online - saying the first account of it was actually a short story, a fabrication, a myth, and it ended up as propaganda. God on our side.

But what a story, what a fabrication, what a myth. An image that’s endured. An image of transcendence and hope.

That Christmas truce, soldiers coming out of the trenches, laying down arms for a while to play football in No Man’s Land. A wee kickabout. Then back to the bloodshed.

I must have fallen asleep eventually, the way you do. Grey morning light came in the window. My father was setting the fire, my mother at the cooker, frying bacon and eggs, potato scones.

I shook off the grogginess, remembered. It was Christmas Day!

I climbed out of bed, rubbed my eyes. The washing on the pulley was just itself again, hung limp.

Piled on my blue chair - and there it was, a blue chair - were my presents, wrapped in crinkly paper decorated with Santas, reindeer, stars. I tore open the smaller packages first - a Cadbury’s selection box, the Beano Book, Dennis the Menace grinning on the cover.

The bigger present was in a square box. From the shape and feel of it, it might be a garage, a fort. I ripped off the paper, uncovered a toy farmyard - a cottage, a barn, a chicken coop, a little mirror for a pond, all glued to a wooden base. In time - a day or two - it would be commandeered by my toy soldiers, or my cowboys would take up position to fight off the Indians. But right now it was a farm, pure and simple, a place for the little figures I already had - cows and a horse, a couple of sheep and a sheepdog, ducks and ducklings on the same base, a pig, a goat, a hen. I laid them all out, placed in amongst them the milkmaid carrying a bucket, the farmer with a shotgun under his arm.

My father - that young man I remember - had imagined after the war he would somehow get some money, somehow find a plot of land in the country, somehow raise chickens and sell Fresh Farm Eggs. Where did that come from?

At school we played a game and sang. The farmer wants a wife…The wife wants a child…

We danced in a big circle. The child wants a dog…The dog wants a bone…

The soldiers were on the march, the Indians were circling, the cowboys were armed and ready. But right now, on Christmas morning, the farmer and his wife stood in their yard. The cattle were lowing, the Christmas angel had come to call, and everything was fine.

When old Scrooge skipped out, tripped out on Christmas morning he declared himself as happy as an angel, shouted out Merry Christmas to the whole world.

Wee boy washed up on the shore. Syrian refugees arriving in Glasgow. Bombers flying out from Lossie. War is over, if you want it? Speaking as a nation. God bless us every one. God help us all.

© Alan Spence, 2015

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here