Scottish scientists have helped create the first map of hotspots for new viruses including Ebola that are suspected of having passed from bats to humans.

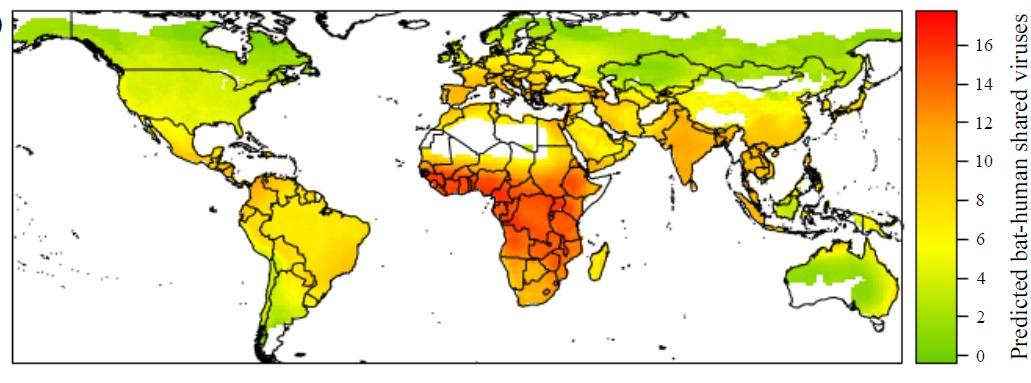

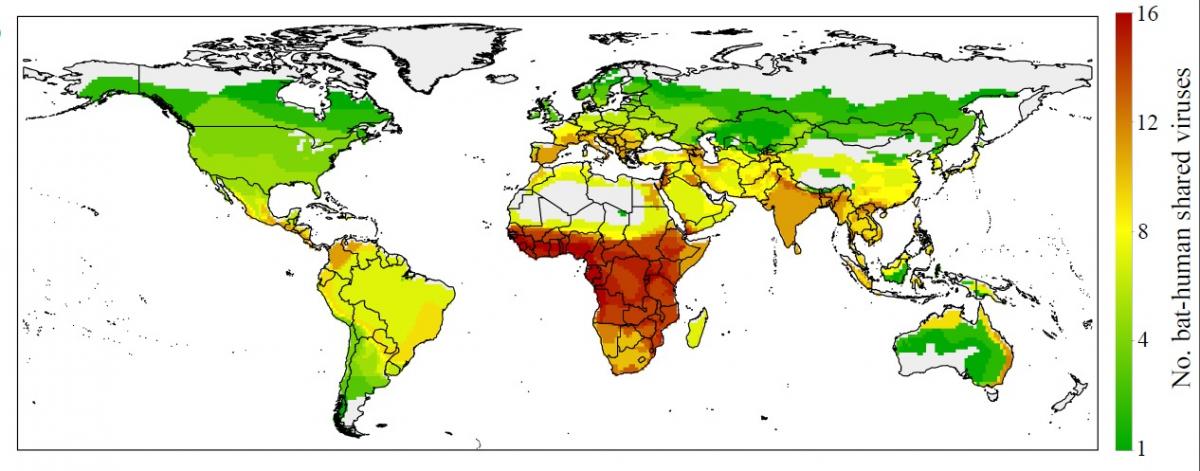

Experts from Edinburgh University, University College London and the Zoological Society of London mapped areas that are most at risk from bat viruses “spilling over” into humans resulting in new emerging diseases, including West Africa, sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia.

Their global map shows risk levels due to a variety of factors including large numbers of different bat viruses found locally, increasing population pressure, and hunting bats for bushmeat.

Approximately 60 to 75 per cent of reported human emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) are “zoonotic”, where infectious diseases in animals are naturally transmitted to humans.

The researchers chose to study bats in particular as they are known to carry multiple viruses and are the suspected origin of rabies, Ebola and sars (severe acute respiratory syndrome).

Liam Brierley, first author and now a PhD student at Edinburgh University, said: “We are seeing risk hotspots for emerging diseases where there are large and increasing populations of both humans and their livestock.

“As a result, settlements and industries are expanding into wild areas such as forests and this is increasing contact between people and bats.

“People in these areas may also hunt bats for bushmeat, unaware of the risks of transmissible diseases which can occur through touching body fluids and raw meat of bats.”

The research, using data published between 1900 and 2013, identified West Africa as the highest risk hotspot for such bat viruses.

This area was outside the endemic range proposed by previous studies but has since experienced the largest scale outbreak of Ebola virus disease seen yet.

Published today in The American Naturalist, the study developed risk maps by identifying different factors which are important for driving the early-stage of the transmission of viruses from bats to humans.

The factors influence specific points in the process which starts with the presence of viruses in the environment and host, progressing to bats and humans coming into contact and ending with successful infection of humans.

Lead researcher, Professor Kate Jones, Chair of Ecology and Biodiversity at UCL Biosciences and ZSL, said: “We’ve identified the factors contributing to the transmission of zoonotic diseases, allowing us to create risk maps for each.

“For example, mapping for potential human-bat contact, we found Sub-Saharan Africa to be a hotspot.

“Whereas for diversity of bat viruses, we found South America was at most risk.

“By combining the separate maps, we’ve created the first global picture of the overall risks of bat viruses infecting humans in different regions.”

Information on the viruses carried by bats was collated by scientists at Western Michigan University and EcoHealth Alliance, both USA, who analysed over 110 years of data spanning 33 zoonotic bat viruses across 148 bat species from 453 literature sources.

Mr Brierley added: “We’re pleased to have collated ecology, epidemiology and public health information to identify the factors that drive virus sharing and we hope it is used to improve surveillance of emerging diseases and inform decisions about preventative action.

“There’s still some way to go in monitoring virus diversity in wild animals and specific information on infections that would allow us to create higher-resolution maps.

“With advances in technology, we anticipate the way we collect and share data to improve, potentially stopping future pandemics.”

Deaths through bat bites are unusual Europe but in 2002, Scottish bat handler David McRae, from Angus, died after contracting rabies from a bat bite.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here