IT was a cold, bright, Monday afternoon when dozens of strangers gathered to say goodbye to a man they never knew.

They filed in to St Simon’s church in Glasgow’s West End last Monday to commemorate the life of a man who has been described as Scotland's version of the silent, sad, lost, but much loved, character Lennie from the acclaimed John Steinbeck novel Of Mice and Men.

The man was Ian Neilson. He had spent at least two decades of his life as an elective mute, choosing not to speak and instead using hand signals if he needed to communicate with anyone.

The 69-year-old, who is believed to have had mental health problems including OCD, had also kept a pet mouse in his jacket – just as the character Lennie did in Steinbeck's novel - as his only form of company in his otherwise completely secluded life.

After his death at the Bellgrove Hotel, a hostel for homeless people, on January 21, his body lay unclaimed in a city mortuary for six and a half weeks as police were unable to trace any of his relatives.

Despite issuing appeals through local media, nobody came forward so volunteers from a night shelter Neilson had attended generously took on the responsibility of planning his funeral, determined to give him a dignified send-off.

Staff at the Bellgrove, where he had lived for almost a decade, said he was found dead during a routine check one morning and assumed he had suffered a heart attack during the night. He had no problems with alcohol or drugs, and police confirmed there had been nothing suspicious surrounding his death.

Volunteers from the Wayside Club night shelter, where he had eaten almost every night for the last 20 years, spoke of Ian as a loner figure and as someone who had “slipped through the system”.

At his funeral, around 80 people squeezed in to the church. The congregation knew little of Neilson but it was essential for them to commemorate his death with respect - a chance to show that people care for the weakest amongst us all.

Despite classing him as a “Waysider” due to his frequent attendance at the club in the centre of Glasgow, volunteers there said even they knew practically nothing about him.

The man had spent at least 21 years living under the radar and made the choice not to speak despite having the ability to.

When asked why this may have been the case, those who had met him could only guess. Some said he was so private and secluded that he just did not want anyone to know anything about him, while others guessed it was due to a trauma or some painful incident which had led him to the life he lived.

Every day he would leave his room at the hostel in Glasgow’s East End around 3pm, and wander the streets for hours before heading to the Wayside for dinner around 8pm.

Staff at the Bellgrove said they had tried to get him help on at least three occasions, attempting to put him in touch with psychiatrists and the council’s social work department but had no success.

One staff member told the Sunday Herald: “Ian’s just one of those poor guys who are in the system, you see them walking about the streets. There are a lot of people walking about with mental health problems who are slipping through the net, and Ian was one of them.

“He first came in here on November 13 2006, and you couldn’t get a word out of him. He did everything by hand signals, he could speak okay but he just didn’t want to talk to anyone.

“He stayed in the same room in here, and he wouldn’t engage with anybody. Two or three times we tried to get him help through the social work, with psychiatric nurses but he wouldn’t engage.

“If anyone came to speak to him he just switched off…He wouldn’t see them, or he would just leave the building.

“He is just one of a large number of men who haven’t got any particular alcohol or drug problem, he had none of that, but had a problem with his mental health.”

Neilson avoided all interaction with people or services which could force him to give details about his life, and even avoided attending most facilities for the homeless where he would have to give his name.

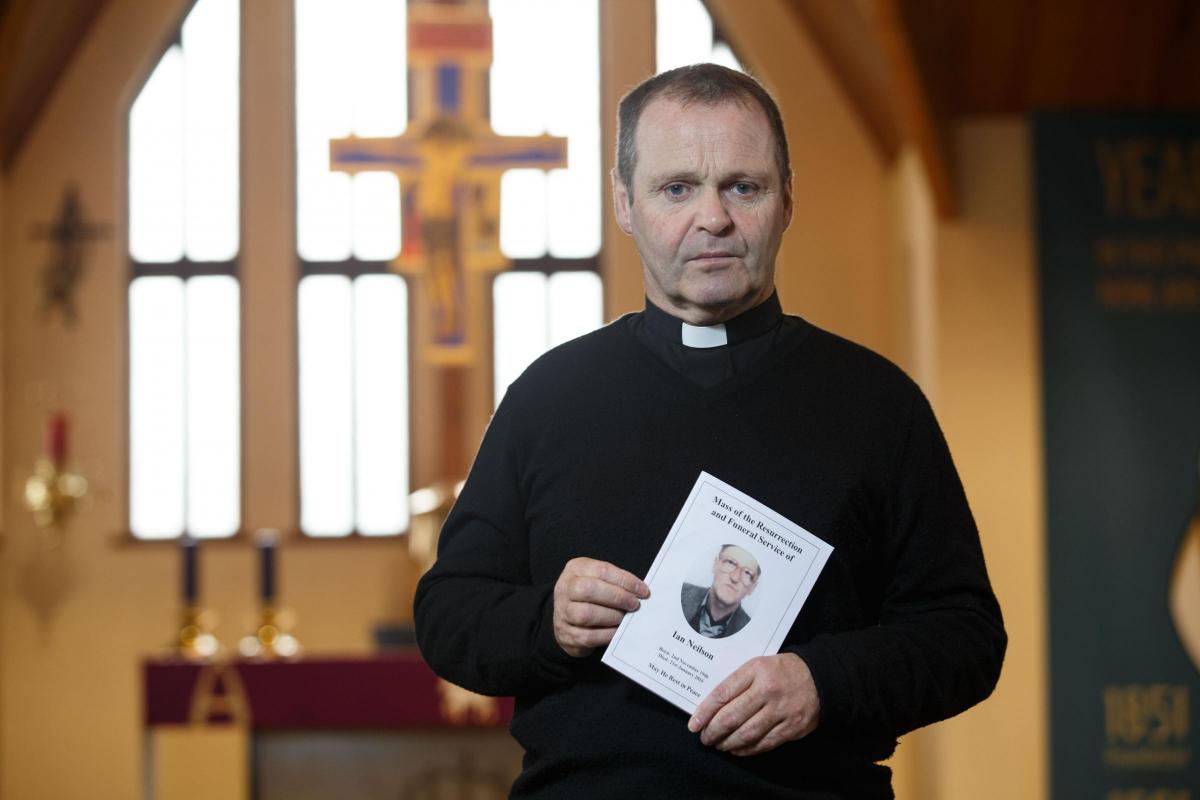

Fr Jim Lawlor who conducted the funeral, said he was moved and intrigued when he heard Neilson’s story, and admitted that in the eyes of many people he would have been seen as a failure.

During the service he quoted the Robert Burns poem To A Mouse, focusing on the lines “The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men gang aft agley.”

Lawlor said: “One of the volunteers remembered he used to have a pet mouse for a while, he would carry it about with him. Ian related to the world through this mouse. It struck me as a handle to understand Ian’s story.

"In the eyes of the world Ian’s life has gone agley… In the world that we live in he would be deemed a failure, non-productive, a mentally-ill homeless guy. But it’s more than that. His plans might have gone agley but he was still a human being.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel