A maid who became a skilled astronomer; an aristocrat who became an engineer; a marine biologist who grew up in poverty but ended up having tea with the emperor of Japan.

These are just some of the examples of trailblazing but forgotten Scottish women who rose to the very top of science at a time when the field was dominated by men.

Catherine Booth, a science curator at the National Library of Scotland (NLS) in Edinburgh, has been carrying out research over the past few years to uncover their fascinating – and often little known – stories.

She has compiled a list of around 30 women in different scientific fields, stretching from the 18th to the 20th centuries, who pursued their careers despite living at a time when they did not have access to the same opportunities as men.

Booth, who will give a talk on her findings at the NLS on July 26, said there were well-known examples such as Mary Sommerville, the 19th century scientist whose work in astronomy led to the discovery of Neptune. She will feature on Royal Bank of Scotland £10 bank notes next year - the first woman to do so, apart from the Queen.

Booth said: “As soon as I started looking I found all kinds of names popping up and pursued their stories.

“They are women who have achieved really quite amazing things in different scientific disciplines.”

Here we look at some of the stories of the ‘forgotten’ Scottish female scientists.

Victoria Drummond was born in 1894 and came from an aristocratic background – she grew up in Megginch Castle in Perthshire and was the goddaughter of Queen Victoria. But from an early age, she was determined to be a marine engineer.

Her father sent her off to be an apprentice in a garage in the expectation she would soon give up the idea. Instead, she completed her time there and went off to train at the Caledon shipworks in Dundee, the only women among 3,000 men.

She was undeterred even by an accident in which she was crushed under a ten-tonne lorry, which left her with a broken collar bone and ribs.

In 1922 she joined her first ship and qualified as the second engineer. When she visited ports she is often said to have swapped her boiler suit for a posh dress to have tea with local dignitaries, as a result of her family connections.

In August 1940, Drummond was the second engineer on the cargo ship Bonita as it sailed across the Atlantic carrying good to the US. It came under air attack from the Nazis but she managed to keep the engines going to speed up the ship and dodge the bombs, for which she was awarded a bravery medal.

However despite trying numerous times, she never passed the test to allow her to become a chief engineer in the Merchant Navy – with hints that the reason why was that a woman would never be allowed to pass the exam.

Instead Drummond, who died in 1978 at the age of 84, qualified as a chief engineer to sail under a Panamanian flag, became the first British woman member of the Institute of Marine Engineers, and carried on working into her 60s.

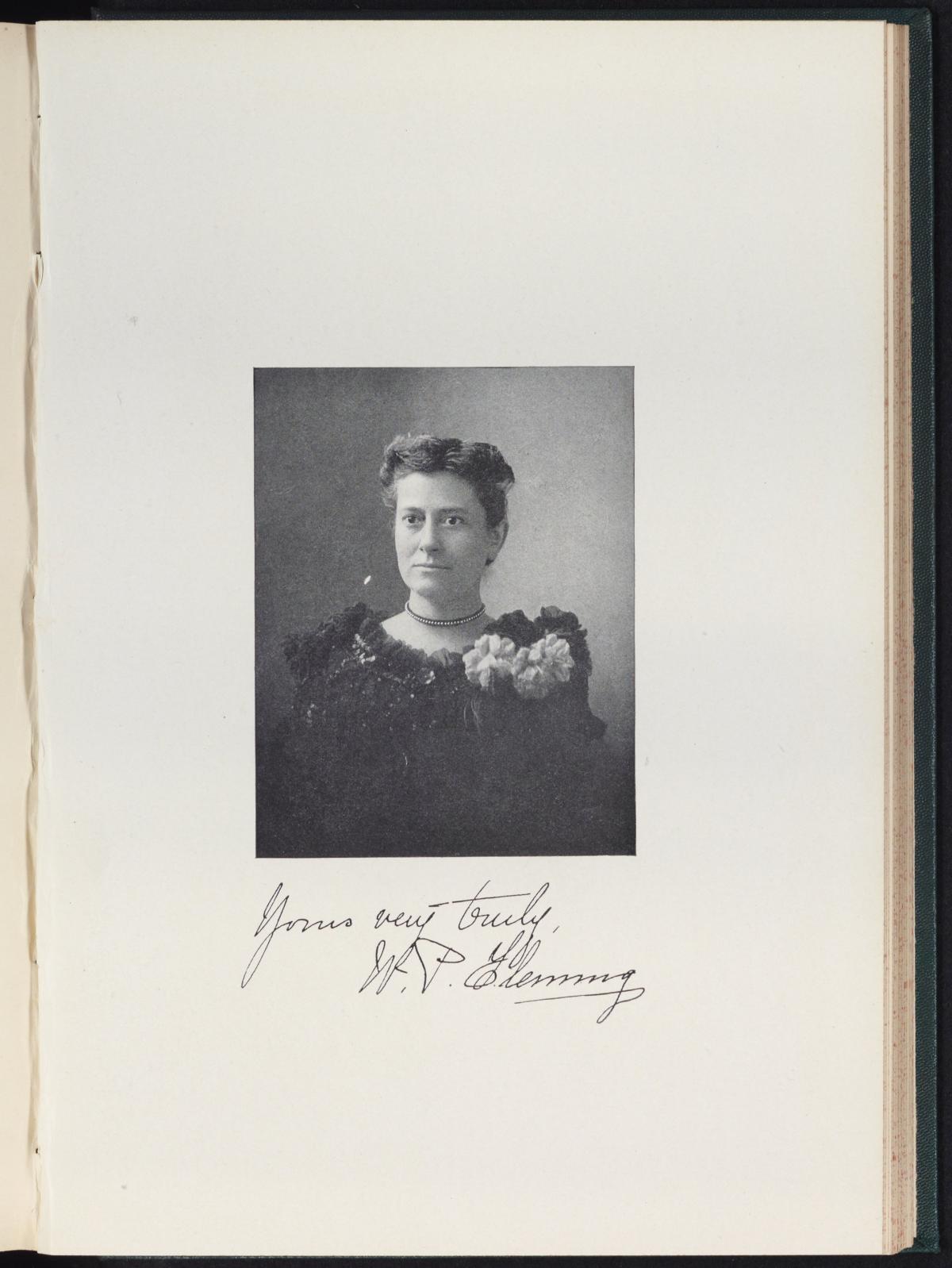

Williamina Fleming – who was known as Mina - was born in Dundee in 1857 and emigrated to Boston in the USA after marrying bank worker James Orr Fleming at the age of 21. But when she was pregnant her husband abandoned her and she was forced to find work to support herself and her son.

She found work as a maid in the household of Edward Pickering, an astronomer who was director of the Harvard Observatory. He hired her to take on the role of examining spectra – light radiating from stars and other celestial objects – on photographic plates, which at the time was a new technique to examine the night sky. Fleming examined thousands of plates and devised her own classification system for them, known as the Pickering Fleming system.

Her discoveries include hundreds of stars and clouds of gas and dust in space known as nebula, including the famous horse-head Nebula in the constellation of Orion.

She was made an honorary member of the Royal Astronomical Society of London in her lifetime – but women were barred from being ordinary members. Fleming died of pneumonia at the age of 54. In 1999 a forgotten time capsule buried at Harvard University in at the turn of the 20th Century was uncovered, which included entries from Fleming’s journal – in which she complained that women working at the observatory were paid far less than the men.

Isabella Gordon was born in 1901 in Keith, Banffshire, to an ordinary working class family who had little money. But she managed to get a bursary to complete her education at school and went onto Aberdeen University.

She was awarded a research scholarship to study for a PhD and went to Imperial College in London where she specialised in studying echinoderms – ‘spiny’ sea creatures such as starfish and sea urchins.

For most of her working life she was the crustacean expert at the British Museum of Natural History, now known as the Natural History Museum, and was the first woman to be appointed to a full-time scientific post there. She travelled to laboratories in the US and Jamaica and published more than 100 articles, reviews and reports.

Gordon was never elected to the Royal Society in London or Edinburgh – the reasons why are unknown, but there is speculation it was because of her working class roots. However she was awarded a medal from King Leopold III of Belgium, who was an amateur entomologist.

But the highlight of her international career was an invite to Japan in 1961 to attend the 60th birthday celebrations of Emperor Hirohito, who was a keen marine biologist. She is said to have had a personal audience with the Emperor and was treated as an “honoured guest”. She became the only non-Japanese member at the time of the Carcinological Society of Japan, which is dedicated to the study of crustaceans.

Gordon was known as the “grand old lady” of carcinology and was awarded an OBE in 1961. She died in 1988 at the age of 86.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here