AT the start of November last year, Daniel Fooks joined his elder brother and younger sister in a rite of passage which, though utterly specific to them, would be recognisable to anybody, anywhere, at any time in human history: a death-bed vigil.

Facing his last hours with his three children around him was their father, Chris, who had been diagnosed with cancer of the lower intestine two and a half years earlier. At the start of 2016, after a long course of chemotherapy, he had rallied and been told he was cancer free. But by April the cancer had returned and this time it had spread to his liver. He died at home in Livingston, in no pain, on the evening of Friday, November 4, 2016. He was 74.

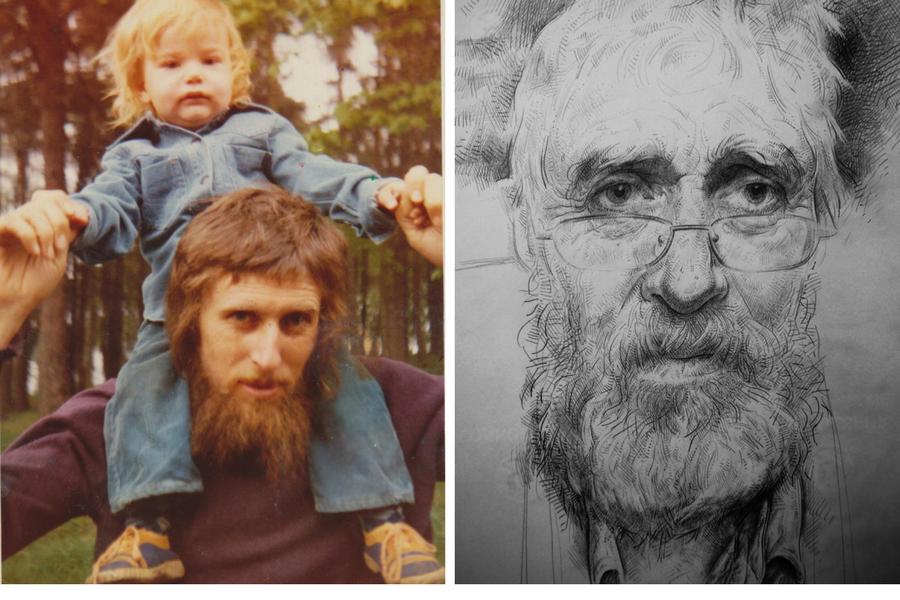

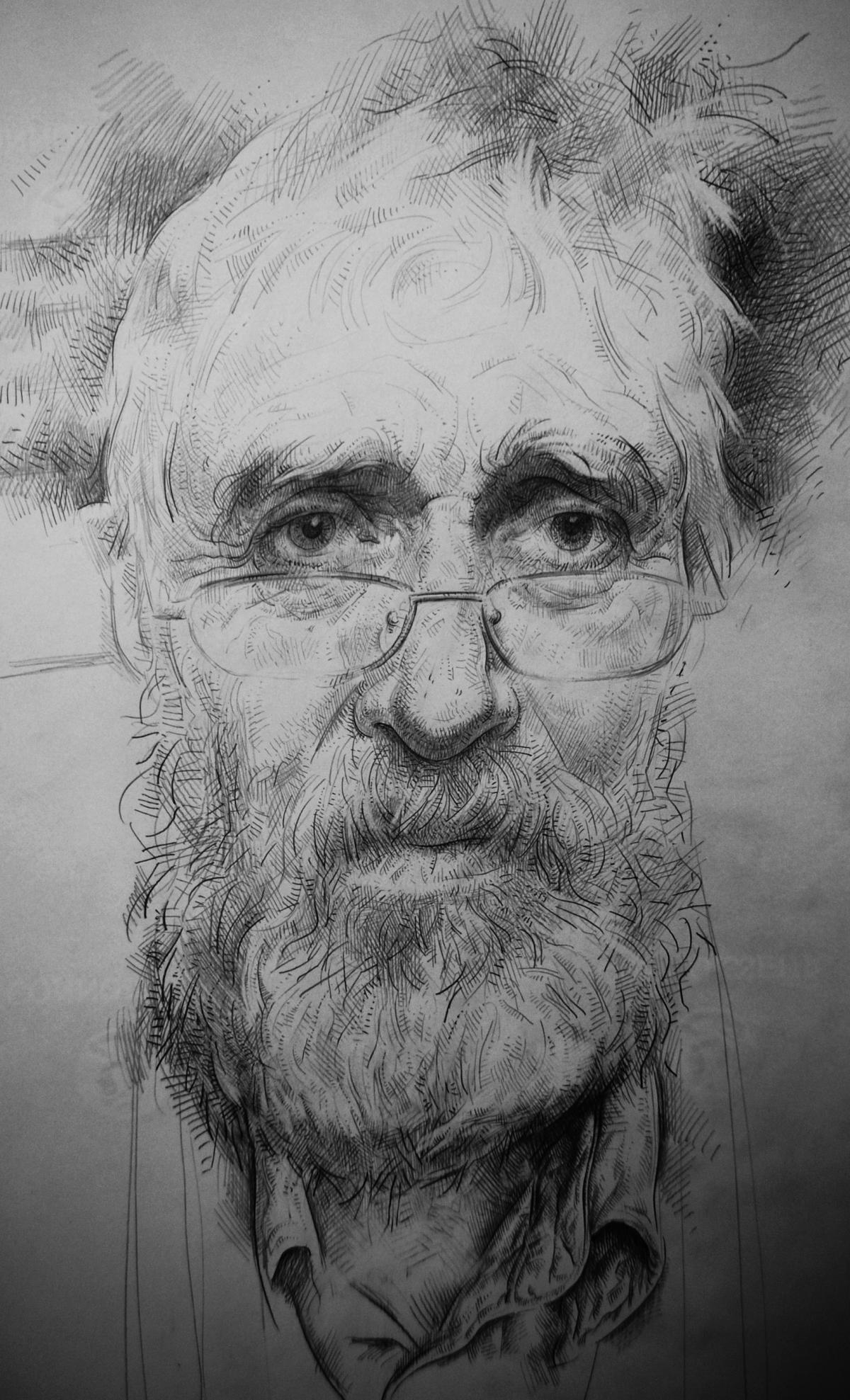

What made this death-bed vigil unusual, however, was what Daniel Fooks was doing as his father lay dying: he was drawing him, just as he had drawn him throughout the chemotherapy process. Just as he had drawn him, in fact, since he was first able to pick up a pencil and sketch faces on paper with any degree of verisimilitude.

There are a dozen or so of these death-bed drawings and they are, collectively, an extraordinarily powerful suite of works. I know, because they're ranged on the floor in front of me when we meet at the Edinburgh home of Fooks's mother, Jean, who had separated from Chris two decades previously. Now Fooks, an artist who has made celebrity portraits of Peter Capaldi, Olivia Colman and Billy Bragg in his time but who has previously shown no interest in selling his work or even exhibiting it, wants everyone else to experience that same power. He wants a gallery to agree to show the collection – notionally titled Not Dark Yet – and to give his father the sort of tribute he feels he deserves.

“Nothing's for sale, it's not about that,” he tells me. “I'm just looking for somewhere in Scotland to show them. I've never been that interested in exhibiting or anything like that. But with these, as a tribute to him or as a memorial, I want his name out there.”

It's hard to believe he'll be short of offers.

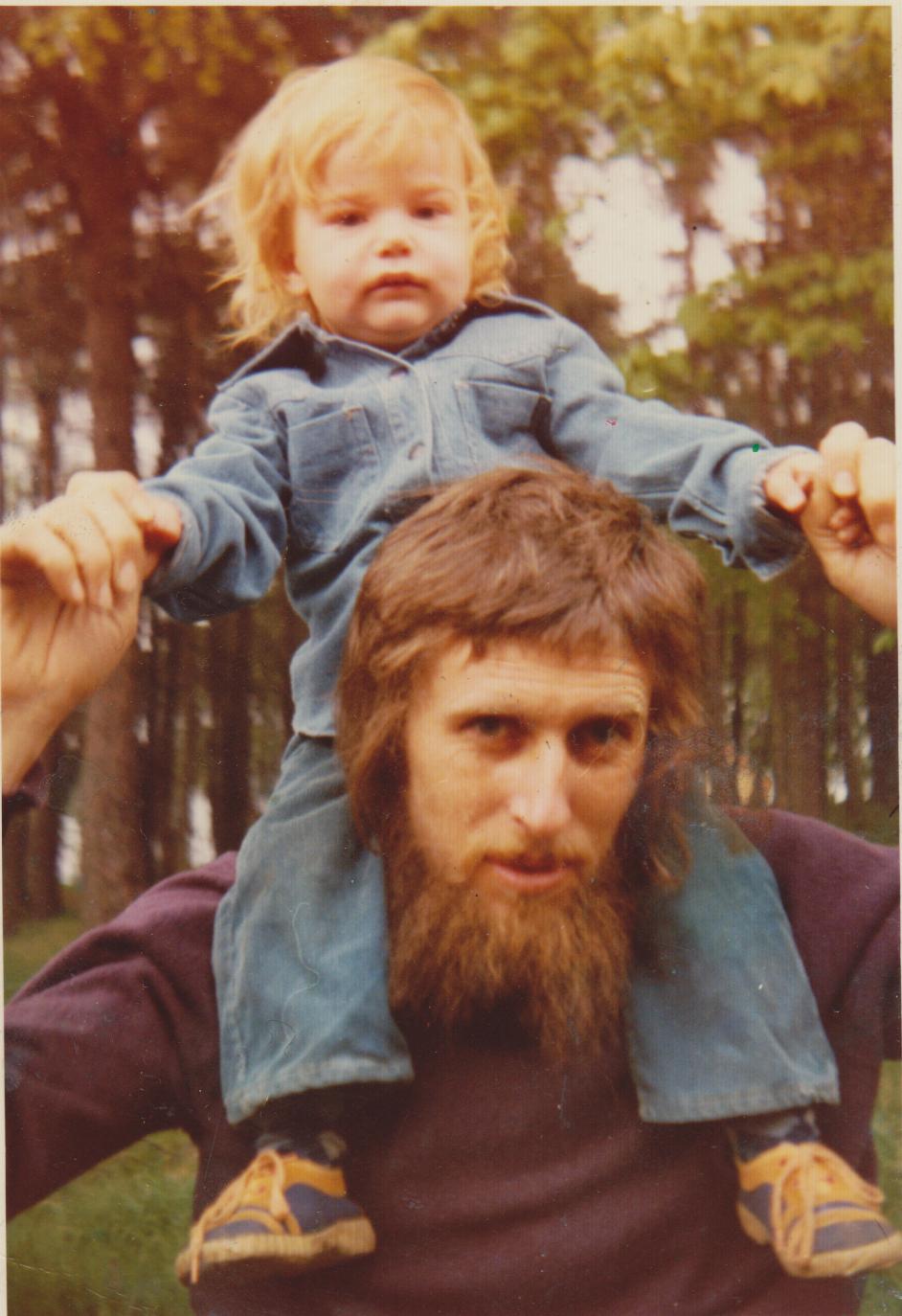

Fooks had always drawn his father. “Since the age of four,” he says proudly as he roots in a cupboard for one of the earliest examples. He comes out clutching an extraordinarily energetic sketch, rendered in vivid black pencil lines and easily distinguishable as a bearded man. Fooks grew up to study painting at Edinburgh College of Art, is now head of art at Godalming College in Surrey and has had his work exhibited in the BP Portrait Award Exhibition. Looking at this early study of his father, it's easy to see why. “I remember doing that sat in a tiny wee chair,” he says proudly. “And I've drawn him all the way through, and my mum. So it just seemed a natural project.”

Maybe not that natural. It's one thing to draw family and friends as they're reading or posing or propped up in bed. It's quite another to draw them dying – and to have to ask prior permission to do so. That conversation happened soon after Fooks heard the cancer had returned and, appropriately, took place in front of a painting.

“My dad had always wanted to go and see Oskar Kokoschka's painting The Tempest, which is in the Kunstmuseum in Basel,” he explains. “So when he told me the cancer had come back I said 'Right I'm buying you tickets for Switzerland'."

Chris thought his son was packing him off to a clinic specialising in assisted suicide - or pretended to, anyway.

"He said 'I want to see the return tickets!' I said 'No, no we're going to see the Kokoschka'. So we went to the museum and saw it. But by coincidence we also saw Holbein's Dead Christ.”

Holbein's chilling work – full title The Body Of The Dead Christ In The Tomb – was painted in 1521 and shows a side view of a bony, angular Christ laid out on his back, the narrow frame pressing in like a coffin lid.

“We were standing in front of that and I said 'When the time comes, would you be offended if I drew you?' He said not at all. He actually joked. He said 'Stick an apple in my mouth and call it Still Life With Old Man'.”

But amid the gallows humour, did Fooks ever feel he was exploiting his father?

“No, because I knew I had to do them and I knew I'd witness something that was so intense and so strange,” he says. “But yes, I am aware that some people might think that. But f*** 'em. I draw and paint to make sense of my own day, my own life. It's my business.”

Again, however, it's one thing to decide in principle to draw a dying father, quite another to find the depths of concentration and emotional courage required to actually manage it when the time comes. And, predictably, Fooks struggled.

“By the Thursday he was on his way out, and on Friday he was out of it. He didn't die until that night but during the day I did a lot of drawings. These works” – he gestures to the drawings on the floor – “were done a few weeks after. The sketches, to be honest, weren't up to much. They weren't great. I just wasn't in that space. To draw takes a lot of concentration and focus. But while it was actually happening I was finding it quite hard”.

He took photos, too, though he will never show those to anyone. “I would feel it was a bit of an invasion of his privacy,” he says. “Even though he'd have been fine with that.”

CHRIS Fooks was born in Tasmania in 1942 and as a young man he worked on dams in the Australian island state. The way his son tells it, he went out one day and got drunk, as young men do, and woke up with a round-the-world air ticket in his pocket. It was on the Greek leg – in Crete, in 1966 to be precise – that he met Jean. Eventually they wound up back in Scotland where they settled in Livingston and had three children: Daniel, the middle child; elder brother Simon, who works in IT (“the black sheep of the family,” Fooks jokes); and younger sister Jo, a noted saxophonist who studied at Boston's famous Berklee College of Music and later joined Humphrey Lyttelton's eight-piece band.

Chris Fooks made his living in children's theatre, running a company called Brassneck. Fooks shows me photographs of him in various costumes – he's a lively looking character with a sparkle in his eye – as well as hand-made posters for the theatre company. In later life he wrote plays and film scripts.

“He was absolutely remarkable,” says his son. “We were very close and we'd stay up all night chatting. I'd say to him 'Are you not scared? You're allowed to panic'. He said 'What's the point?'.

“And he was able to compartmentalise it in a way that I couldn't. He was able to put it in a box, put it to the side, and say 'There's no point opening that. Today, I'm fine, the sun is shining, I'm going through to the Cameo' or whatever.”

A keen cinemagoer, he could often be found in Edinburgh's much-loved arthouse cinema. It was through his love of film that he became friendly with the director, critic and author Mark Cousins, and after his death a memorial was held for him in the Cameo bar.

Fooks shows me a drawing he did of Cousins, just one of a celebrity portfolio which includes paintings of Billy Bragg and Peter Capaldi, as well as exquisite drawings of fellow actors Olivia Colman, David Morrissey and Kenneth Cranham.

“I don't think you have to be close to someone or know them to do an interesting, felt, honest portrait of them, and that's part of the mystery of the process,” he says when I ask about the appeal of the celebrity portrait. “What is it to know someone anyway?”

Next up for Fooks is a session with actor David Hayman (“He's got a great head”) and a couple of weeks before we meet he drew the much-loved children's author Raymond Briggs. Again, he has no plan to show these works.

“I'm just trying to find my way into an image and into my sense of what that picture is,” he explains. “Whether that has anything to do with the real Billy Bragg or the real Olivia Colman, I don't know them from Adam and Eve. I'm just trying to find an image through their features which resonates with me and connects with my own experience. That's why all art is self-portrait. It's all about me, it's not about them. I'm using their wrinkles to riff on.”

But he does make a distinction between the celebrity portraits and the drawings of his father.

“I did them [the portraits] the best that I could, but the ones of my dad, that felt different," he says. “My dad always used to say – it was his line – that artists are born with two eyes: one for looking out the way and one for looking in the way, and the trick is to use both at the same time. And I think with these drawings, I was looking in the way as much as I was out. So they're the most personal drawings I've ever done and the most important drawings I've ever done.”

I wonder if that feeling that these works are different and important is connected with an ongoing grieving process. After all, it's still less than a year since his father died.

“I just knew I had to do them,” he replies. “I don't know if that was part of the grieving process or whatever. But it was a way of coming to terms with it. Witnessing the death of someone you love and are close to is a very odd and intense and overwhelming experience.”

What he does know is how he felt when he returned home to his family in Surrey in the days after his father's death.

“One of the first things I said to my wife was 'I've got art in me. I have seen something and been through something and I have something I need to get out.' It was fully formed and I just knew I had to get it out. He'd given me one last gift. I knew what to do.”

And so he did it. And now the art is out and on paper and it needs to be seen. Not because Daniel Fooks craves acclaim or even attention, but because of another idea that will be familiar to anybody, anywhere: the idea that art can defeat death.

“I need it to last,” Fooks says simply, looking down again at the sketches of his dead father strewn across the floor. “But I'm going to miss that old bastard for the rest of my life – and doing a couple of drawings isn't going to sort that”.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here