IN 2015, a robot in Japan found itself being bullied by children. Robovie 2 was stationed in a shopping mall in Osaka. When Robovie 2 found its path impeded by mere mortals, it would politely ask them to get out of the way. Most adults did, as did most children - when they were on their own ... but when they moved around in groups, children would obstruct the robot and even become violent towards it.

So, researchers re-programmed it. They realised that children were less likely to behave in this way if an adult was nearby, so when the robot detected a group of little people it would change direction and steer towards a big person. It offered valuable insight into the increasingly important issue of how humans interact with machines.

I'm told this story by a small team of researchers in Scotland, based at Heriot-Watt University's Centre for Robotics in Edinburgh. They're currently more than a year into the SoCoRo project, which hopes to make breakthroughs in autism therapies. They’ve got a robot named Alyx which has been learning human facial expressions, which could eventually form the basis of a therapy for people living with autism who find it difficult to recognise emotions. They believe that robots could help enable people with autism to overcome social obstacles that are hindering them in the workplace, and their work in the field is opening fascinating doors about human-robot interaction.

"Only 16 per cent of adults in the UK who have autism are in full time employment," says the project's psychologist Peter McKenna. "The idea is that a robot would be particularly useful for this purpose because it provides a watered down version of a conversation partner.

"When you and I interact there’s lots of signals being passed back and forth, and for us to respond appropriately we have to process those signals and come up with generated behaviour that’s appropriate. For some adults with ASD [autism spectrum disorder], the processing of those signals can be quite overwhelming, so we’re running on the hypothesis that using a more simplified presentation of a human could be a useful way to train those adults in their understanding of those social nuances."

Their area of research throws up lots of things to think about. In one of their experiments, they introduced Alyx to members of the public at Glasgow Science Centre, and asked them to offer it food and then decide from Alyx's expression whether the robot approved of the choice. People didn't find it as easy as the team might have expected.

"Some of the expressions were clearly read as we intended, but some were more ambiguous, and that was interesting from the perspective of emotions and how we generate them from the human side. So, for example, the robot would wink but it was quite a slow, delayed wink, and people thought that was negative, whereas if you wink at someone quickly it’s got a very different social representation.

"You can see why robotics is really interesting because we get to pick apart these nuances and study them in a quite different way."

While humanistic robots may be not be right around the corner, human interaction with transitional tech is rapidly increasing. It’s not uncommon for people to find themselves losing their tempers with Alexa, the home-based technology that interacts with families through speech and which can play music, or change TV channels, without anyone having to lift a finger.

Meanwhile, concerns have been raised in some quarters that the creation of ‘sex robots’ could be damaging to efforts to stop violence against women. If men become used to robots that cater to their every whim without complaint, will they come to expect it from real women, too?

According to Thusa Rajendran, another psychologist in the team, the key to stemming a rise in antisocial behaviour accompanying advances in tech is in design, and that’s why putting robots into shopping malls or teaching them facial expressions isn’t just a stunt or a gimmick.

“If you build the tech without thinking about how people behave, there’s a risk, but you can engineer it so that it brings out the best in people rather than the worst in people,” he says. “If you don’t have that design thought out at the very beginning you have all these unintended consequences, where people think they can just kick it in because it’s a machine.”

According to the team, the Robovie 2 experiment was an essential insight into the dangers lurking ahead if design and human behaviour isn't to the fore when it comes to the advancement of robotics, but the team is optimistic are don't believe developers will not 'put the human into robotics'.

"Researchers working in the area of AI would have to be negligent in their development in allowing things to go down that direction," says Dr Frank Broz, deputy head of the robotics lab. "We are quite aware of the ethical implications of our work and there’s already a lot of discussion in the AI community about how we can prevent undesirable outcomes."

ROBOTS WE CAME TO LOVE

SHORT CIRCUIT: Johnny 5 is alive! This 1980s classic movie brought robot Johnny 5 to our screens, who longed to be alive like humans and who was beloved by fans

AI: This 2001 Steven Spielberg offering introduced David, played by Haley Joel Osment, as an admittedly creepy child robot. But with his quest to make his human ‘mother’ – his owner – love him, little David tugged at the heartstrings

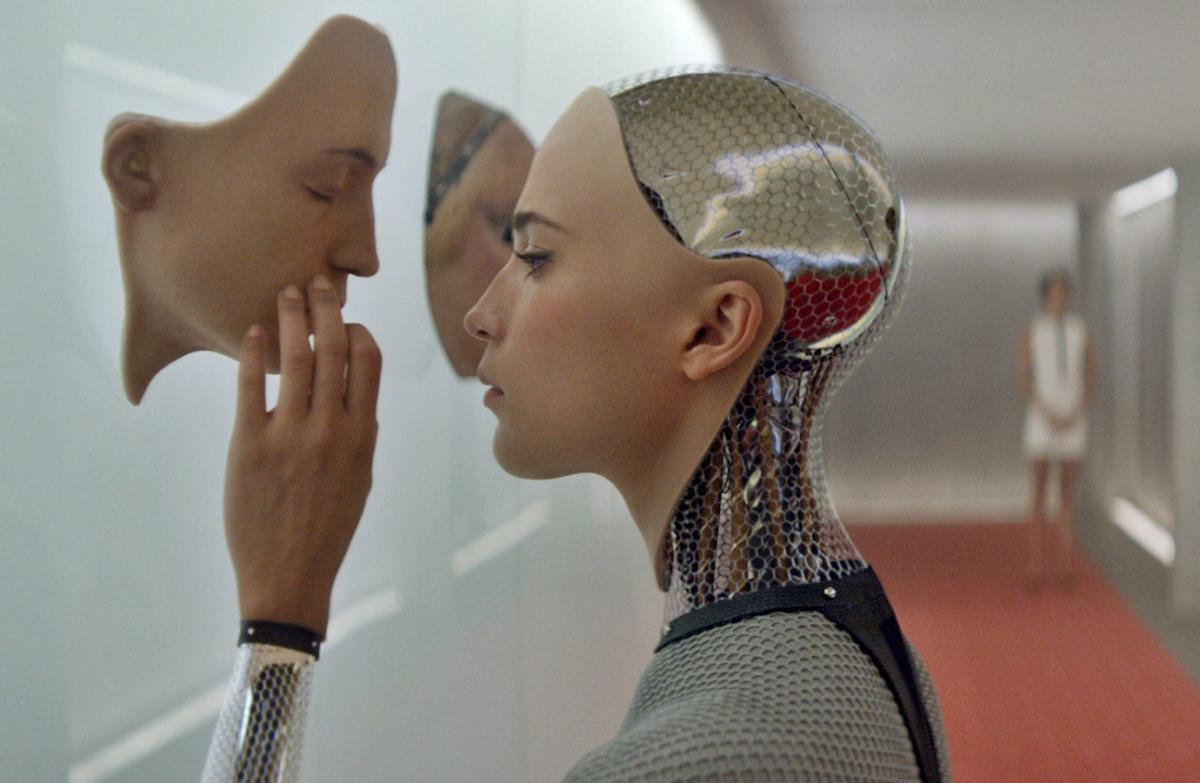

EX-MACHINA: If you’re really scared of artificial intelligence and robots taking over the world, you’re not going to like this 2014 film. Poor programmer Caleb Smith just didn’t have a chance against captivating robot Ava

I, ROBOT: The film, in which arch-cynic Will Smith and robot Sonny save the world from an evil mega-computer, is based on the classic short stories by Isaac Asimov. Suffice to say that, without Asimov's work our modern view of robots would be very different.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel