AN internationally renowned doctor has appealed to dementia patients to donate their brain after death to advance vital research into the causes of the degenerative condition.

Consultant neuropathologist Dr Willie Stewart oversees a “brain bank” – the world’s most extensive collection of brain tissue – at Queen Elizabeth University Hospital in Glasgow.

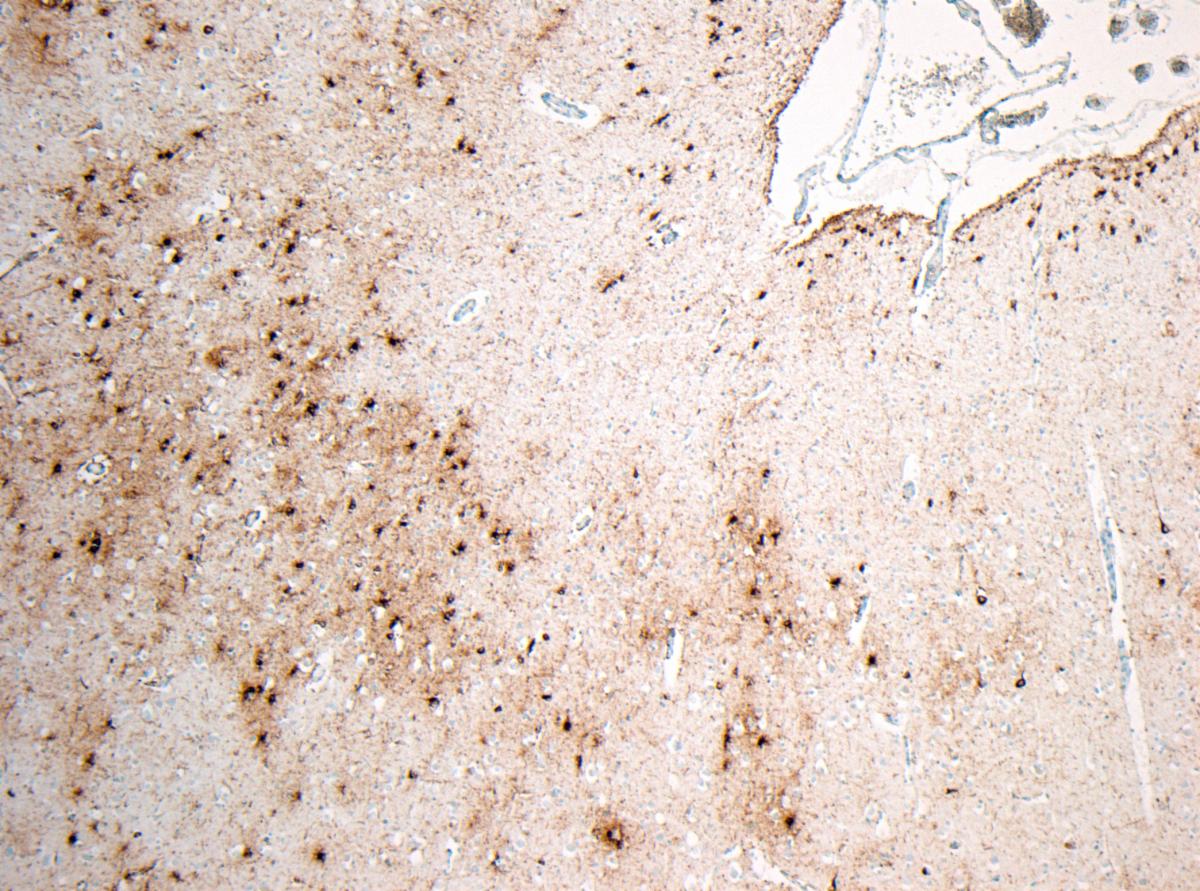

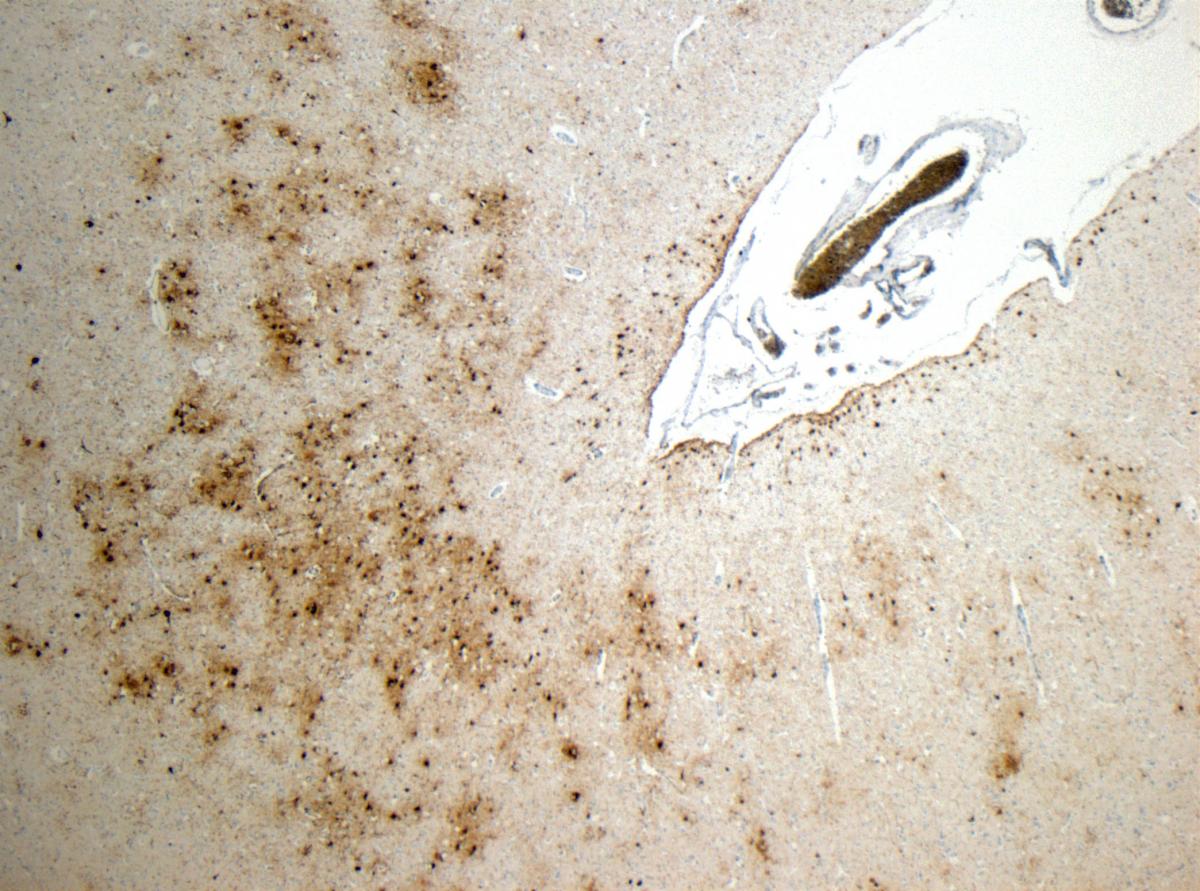

Researchers who use the brain bank are trying to understand the links between dementia and traumatic brain injury (TBI) caused either by a single incident, such as an assault or car crash, or by repetitive head knocks during sports like boxing, rugby and football.

Many people who suffer TBI go on to develop a form of dementia known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), which can only be diagnosed by dissecting the brain after death. But the symptoms of CTE are similar to Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia, meaning CTE is often misdiagnosed.

Former Dundee United footballer Frank Kopel started showing symptoms of what doctors thought was vascular dementia seven years before his death but when Dr Stewart looked at brain scans provided by the footballer’s widow Amanda he found evidence of CTE.

Amanda Kopel is convinced that the former defender’s football career contributed to his death and is backing Stewart’s appeal for more dementia patients to donate their brain to the brain bank.

“It’s going to help people in future,” she said. “A lot people I’m sure are not aware of the brain bank and it’s about trying to raise awareness of it.”

Stewart hopes that if more brains are donated, researchers can eventually come up with a more accurate method of diagnosis so that varying forms of dementia can be treated differently.

He said: “There are dozens of different types of dementia and it’s foolish to believe they’re all the same disease. We know they’re not. So, it’s foolish to believe one or other of them may not be better treated differently. If we just treat them all as one disease we’re never going to make any progress.

“If we did this with cancer a whole bunch of patients would do catastrophically badly because we’re giving them the wrong treatment. Whereas those patients can do really well if we give them the right treatment.

“I think for any dementia we’re only going to get better at understanding it if we look at the brain post-mortem. Unless we start understanding how all these things mix and blend together and cause the problems we’re never going to get better at managing it.”

Stewart said doctors in hospitals would routinely ask bereaved families if they could carry out a post-mortem examination until the Alder Hey children’s hospital scandal in the 1990s changed the culture.

It emerged at a public inquiry in 1999 that staff in NHS hospitals, including Alder Hey in Liverpool, were removing and retaining human tissue, including children’s organs, without consent.

“That was the far end of a spectrum of bad practice,” Stewart said. “In Scotland it was nothing like as bad as that. But it caused us to stop and check how we could do this better. As a result of that there was a review.”

The 2001 review by Sheila McLean, a professor of medical ethics at Glasgow University, found retention of organs by hospitals after post-mortem examination was “standard practice”. Bereaved families now have final say over what happens to the body of their loved one after death.

And Stewart said that change means doctors are less likely to have a difficult conversation with relatives of dementia patients about retaining their brain for research after death.

He said: “It could be because clinical colleagues don’t want to bother us, maybe they are not aware, or perhaps there is something slightly more challenging, that actually they think that by having a conversation with the family about post-mortem they are admitting defeat.

“We know that among patients with dementia and families of patients with dementia there’s a high willingness to do something at death that might make a difference and help to inform us, by donating the brain for research. And we know there are people like me that are more than willing to make that happen. What really, really frustrates is the disconnect.”

Stewart said the process of donating the brain was straightforward and would not delay funeral arrangements.

“Like everything else in life, there’s a form to be filled in,” he said. “It’s not something you want to speak to people about at the time of death or after death. It must be thought about rationally, and the correct paperwork has to be done without the stress of the immediate bereavement.

“Assuming the paperwork has been dealt with, at the time of death the family or the next of kin notify the doctor or the funeral director that this donation has been requested and then arrangements are taken out of their hands. The body is brought in the same day or the next day, the brain is retrieved, and the body is released. For a lot of the specialist tests we need to retrieve the brain within 48 hours. There is never a delay to the funeral.”

Bereaved families can request that the remains of the brain are returned to the body after tissue samples are taken but the majority do not request this, which makes it easier for his team to carry out vital research.

Stewart explained: “When the brain comes out it’s like a soft jelly and it’s very difficult to handle. We can handle it, but it’s compromised when we handle it that way. What we prefer to do is put in a bath of solution which firms it up. It turns it from the consistency of soft jelly to the consistency of a mushroom. That takes several weeks. In those circumstances, with the full of agreement of a supportive family, we hang on to the brain.

“After a couple of weeks of firming up we examine it in detail. So, we cut it up into smaller bits, have a look for all the changes we might expect to see, and take our samples then and look at them down a microscope. What we can do then is dispose of the brain through our respectful disposal mechanisms in our crematoria here.

“Most often what happens is the family agree that we can keep it and continue to research with it and they form part of our brain bank here, which is available to other researchers around the world.

“It’s unique, globally. In this department we have a unique resource. There’s nothing like it in the world. It’s an internationally unique research archive.”

To arrange to donate a brain, Stewart said dementia patients and their families should speak to their doctor or contact the Glasgow Brain Injury Research Group directly using a form on the website: gbirg.inp.gla.ac.uk.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel