The windows of Elgin Cathedral have been deprived of their bright and colourful stained glass since the 1600s.

Falling into disrepair after the Protestant Reformation of 1560, the windows of the Cathedral were destroyed by vandals and later by Oliver Cromwell’s soldiers.

But thanks to state-of-the-art technology, the patterns and shades that once adorned one of Scotland’s most beautiful medieval buildings have now been rediscovered.

Scientific testing has revealed details of the cathedral’s windows, including the patterns, colours and origin of the glass, shining a light on cultures and trade routes at that time.

Helen Spencer, the PhD student at Heriot-Watt who led the study, said: “Worship was a major part of medieval life, and the importance of decorations on church windows cannot be overstated.

“Depending on the time of day, different windows would illuminate the worshippers. Evensong would have a different colour and character to morning worship.

“If we can find what the windows looked like, it can tell us about what religious orders and fashions came in to Scotland, what saints were idolised, who funded the construction of churches, and where the builders, glass and glass decorators came from.

“Unlike most countries in Europe, there is no surviving medieval window glass in situ in monastic or ecclesiastical buildings in Scotland.

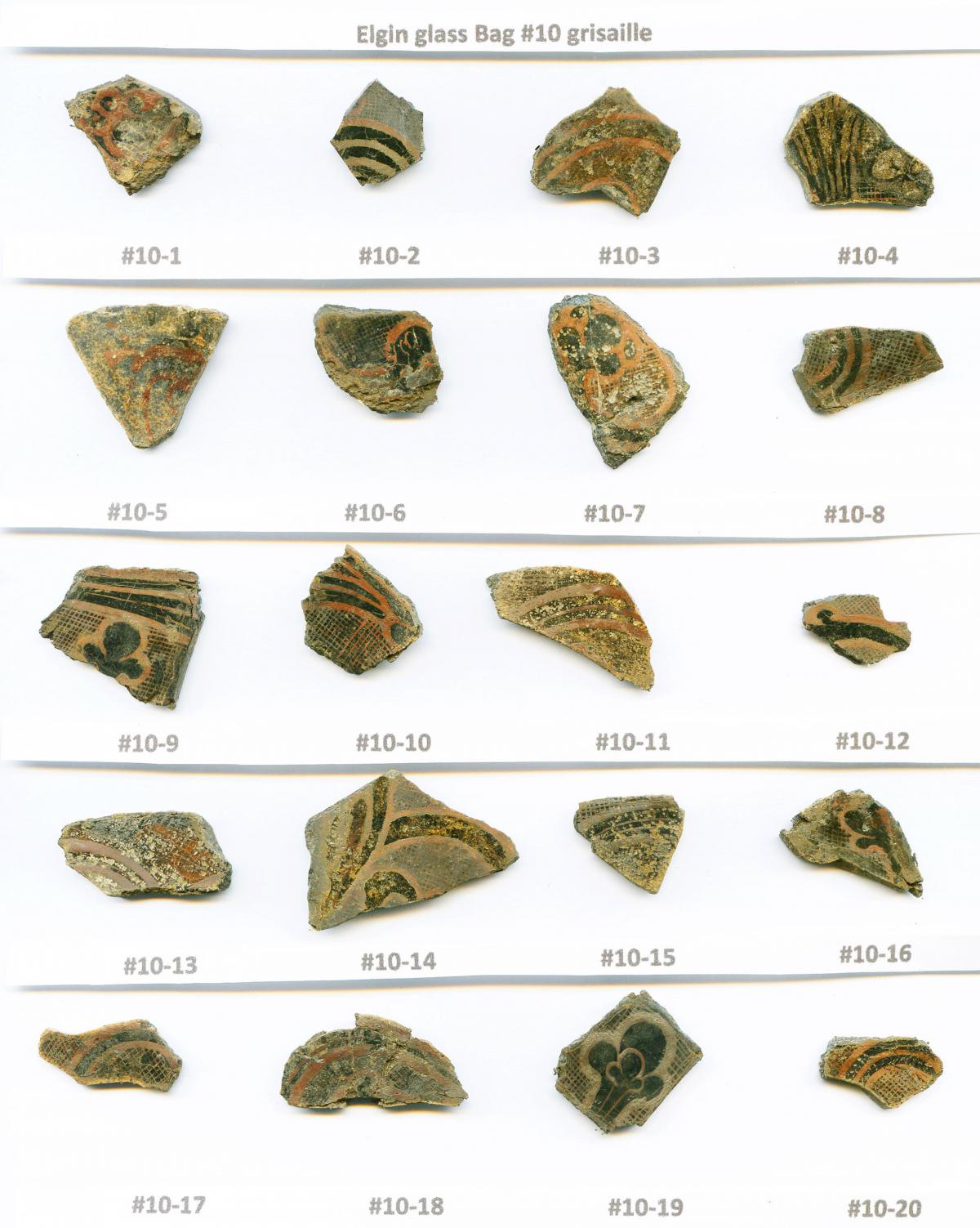

“This means we rely on recovered fragments to learn more about glass from this period.

“The tests we carried out have shed light on the colour and origin of the window glass of Elgin Cathedral.”

Built in 1224, Elgin Cathedral - once known as the Lantern of the North - was the principal church of the bishops of Moray.

However, it was abandoned in 1560 after parliament legislated that the Scottish church would be Protestant and made Catholic mass illegal.

The lead was removed from the building’s roof in 1567 and sold for the upkeep of Regent Lord James Stewart’s army. The windows were later vandalised and destroyed.

However, the site’s fortunes began to change when it became a visitor attraction in the early 1800s.

The recent project examining the glass saw scientists use cutting edge technology including electron microscopy and x-ray fluorescence, as well as the first laser-ablation spectroscopy analysis of medieval Scottish glass.

Ms Spencer said the results showed that most of the glass had its origins in northern France, while a smaller section of it came from Germany.

She added: “We identified two distinct blue glasses, both containing cobalt. While one was very dark and rich in potassium, the other a light blue that is richer in calcium, sodium, phosphorus and aluminium.

“he lighter glass was coloured with bronze, while the darker blue most likely had brass filings added. Both these blue glasses were sourced from different parts of Europe.

“We also found that the brown and amber glasses had quite different base glass ‘recipes’ to the greens and pinks, meaning they were likely made at separate locations before being imported to Scotland.

“Scotland didn’t manufacture glass in the medieval period, although several regions in England produced white ‘colourless’ glass.

“At the beginning of the 13th century, much of the white glass came from Normandy and by the 15th century it was coming primarily from Flanders.

“Monastic connections and new trade routes from present day Belgium that connected to east coast ports like Leith, Perth and Aberdeen all had an impact on the glass that was commissioned and used for these beautiful cathedrals.

“Understanding more about these sites brings them to life. The more we discover about our historic buildings the more we can appreciate our history, how people lived, the connections between Scotland and Europe at that time and the craftsmanship involved.

“The next time you visit a ruin in Scotland, take a look at the window spaces and imagine them filled with blue, pink, yellow, green and amber glass from across Europe.

“It will change how you think about and experience these buildings.”

The project, funded by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland and Historic Environment Scotland, was prompted by a lack of research looking at stained glass in Scotland.

The Heriot Watt team will now test medieval window glass from across Scotland in the first comprehensive study undertaken since the 1980s.

The team hopes advanced testing techniques will uncover more secrets from the country’s cathedrals.

Dr Simon Gilmour, director of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, which part-funded the project, said: “The Society of Antiquaries of Scotland was proud to fund this project.

“The lack of research about window glass used in Scotland during the medieval period was highlighted in the Scottish Archaeological Research Framework and this project has been able to use cutting-edge technology to enhance our knowledge of how these ancient windows were made.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel