SCOTLAND’S most eminent historian admits he didn’t become engaged in arguably the most infamous and traumatic episode in the nation’s history until he was well into his twenties.

“We started going on holiday to the Highlands in the late 1960s, early 1970s and you could still see the traces of dispossession very clearly,” Professor Sir Tom Devine explains. “That’s what’s so interesting when you go to the west coast and the Hebrides, that the marks of this extraordinary process of historical revolution are on the land.”

The visual scars of the Highland clearances he saw half a century ago, the ruins and abandoned townships, had a profound impact on Sir Tom personally and professionally, inspiring much of the work he has undertaken since. And the fruits of this labour have been brought together in a ground-breaking new book that not only adds to our knowledge and understanding of the clearances north of the Highland Line, but also sheds new light on how dispossession impacted on the rest of Scotland.

Indeed, the volume challenges the narrative many Scots have told themselves and others for centuries: we will surely never again be able to refer to the destructive events of the 18th and 19th centuries as the “Highland” clearances.

The name of the book, The Scottish Clearances: A History of the Dispossessed, 1600-1900, highlights Sir Tom’s central premise that what occurred was a deliberate and nationwide process that affected lowland areas as much, arguably more so, than the Highlands. At the heart of the narrative is an evidentially robust but also often grim and very human story of how Scotland was transformed from the rural society of old to the largely urban nation we know today. The end of traditional Highland life is here, warts and all, but crucially so too is the far less well-known story of the demise of an entire class of lowland folk, the cottars.

“One of my main arguments is that the scale of land loss was greater in lowland Scotland and that the scale of landlessness at the end of clearance was also greater,” explains Sir Tom.

“We all know about urbanisation but in terms of Scottish culture, the sheer scale of the revolution is not recognised. In early 18th century Scotland most people living outside the towns and cities of the lowlands and Borders had access to some land because to be without it in that subsistence society was to court survival itself.

“By about 1820 in the lowlands and Borders, the landholding society that had existed since time immemorial, including the quarter to a third of old rural population who were cottars, had vanished.”

As Sir Tom points out, while the wounds around clearance, dispossession and forced emigration remain painful in the Highlands, recognised and revered around the world, kept alive and passed on through families and communities, there has been no such process of grief or remembrance for the lowlands.

“I’ve always been interested in puzzles,” he says. “One of the big questions is this: why in many parts of Scotland did the dog not bark in the night? With the exception of a levellers’ revolt in the 1720s the process in the rest of the country was silent. There is no folk memory of dispossession and that led many people to think nothing had happened, that the whole thing was concentrated on Gaeldom and the Highlands, where it is still a live issue.

“The clearances are something everybody thinks they know about. This book is an attempt – and I’m glad to have been the historian to attempt it, because it’s been absolutely stimulating – to rewrite a central aspect of a nation’s history. It’s very unusual for a scholar to be able to do that, especially your own history.”

Sir Tom believes English popular historian John Prebble, whose best-selling 1963 book The Highland Clearances is the sole source of many people’s knowledge of the subject, has much to answer for in terms of the mythmaking and politicisation that continues to surround this period of history. His new book tells a far more complex - but in many ways no less dramatic – story that covers improvement as well as loss.

“Prebble and I share the same publisher and it was only while going through the Penguin archives that I discovered his book on the clearances is almost certainly the biggest selling on Scottish history of all time,” says the Lanarkshire-born author and academic.

“In his terms the Scots are an ancient warrior race betrayed by their leadership class and pushed off their lands. That kind of human experience, that kind of story, is very attractive. It’s got a psychological impact that is difficult to dislodge.

“But the historian’s role is to be impartial and get as close to what happened and why it happened as possible. People interested in Scottish history in north America still see it through the prism of Prebble’s works. I quote in the book a fifth-generation Scottish Texan lady who hired a genealogy firm to find out where she was from and discovered, like most 19th century immigrants, she came from lowland Scotland, in fact my own place of birth, Motherwell. She was not only displeased but for a time refused to pay them. She wanted Skye, and above all else she wanted a cleared township in Skye.”

It will take time to wean north Americans off their overwhelmingly romantic view of Scottish history. But this is a book that is likely to ruffle feathers closer to home, too. Are we Scots ready to face and reassess our prejudices about the clearances?

“You get the sense that the Scottish nation is now a more confident and sophisticated place,” says Sir Tom. “People may be able to treat the arguments I put forward seriously, without indulging in outrage and invective against the author. I’ve made the evidence base as armour-plated as I can because I know this is going to touch sensitivities, not least in Highland Scotland.”

This latest 400-page tome joins the list of definitive – and also thoroughly entertaining – texts written by the historian over the last 40 years, a canon of modern Scottish history that covers rural society and urbanisation, the impact of Scots migrants across the globe, and Scotland’s role in the Empire and slavery, that is devoured and appreciated by academics and wider society alike at home and abroad.

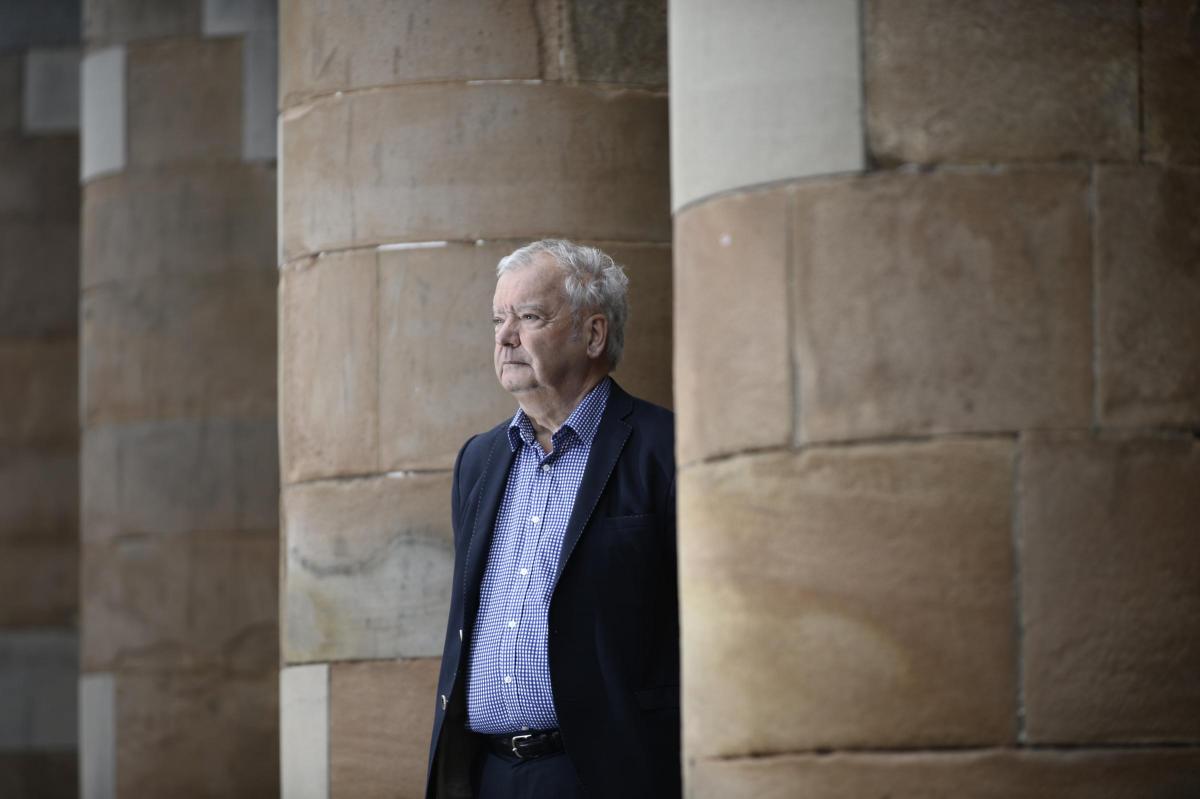

We meet in a hotel in Glasgow’s George Square, a short hop from the City Chambers, where he has come from recording an interview for BBC Radio 4 on the city’s slave history. The 73-year-old is also a familiar face on television, his engaging, accessible style having made him a vital and popular source of information, anecdote and analysis for programmes on everything from land reform to Balmoral Castle.

Speaking of which, what does he make of popular TV history presenters such as Neil Oliver and Dan Snow? An eyebrow lowers and the hint of a wry smile appears across the Devine features.

“I’m not impressed with these people because they can’t be basing what they say on camera on deep knowledge and insight. They’re not scholars. There are plenty of telegenic young historians who could do the job very well indeed.”

That's not to say Sir Tom isn’t rather worried about the future direction of his profession, detecting a “serious weakness” in the current generation of historians researching Scottish history post-1700.

“There needs to be more risk taking in order to start to revise, or at least confront, some of the big issues. My generation is passing away, the next generation should be daring to question us.

“Scholars should be prepared to be in direct interrogation of other people’s work. My subject can only grow if people are prepared to challenge those who went before or are still writing. There’s not enough of that.”

Sir Tom has spent much of his life challenging accepted historical narratives during an academic career that has spanned half a century at the universities of Edinburgh, Strathclyde – his alma mater - and Aberdeen. Earlier this year he was awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award in Historical Studies from the UK All Party Parliamentary Group on History and Archives at Westminster, the first historian from a Scottish institution to receive the award. In 2014 he was knighted.

Not bad for a boy from Motherwell who no one expected to be born at all, after his mother suffered a slew of miscarriages and his elder brother, Michael, died of spina bifida two months after birth. According to family folklore his grandfather, an Irish migrant to Scotland like all his grandparents, spotted early promise in young Thomas.

“Following my brother’s death, people didn’t think there would be any more wee Devines,” says the historian, who lives in Hamilton. “Then I came along and apparently one day raised my head from the cot – it must have been wind – and grandfather declared in his Irish brogue ‘look at that boy already trying to sit up, he’s going to be a professor!’ In those days that was the acme of all achievement.”

His childhood interest in history was initially sparked by military topics – “at 12 I asked my parents for the memoirs of Field Marshall Montgomery” – but he dropped the subject at secondary school in favour of geography.

He talks of the post-war period in which he grew up as a “golden age” in terms of social progress – he eventually swung his allegiance back to history as an undergraduate at Strathclyde university in the 1960s – and is troubled at statistics showing a stark reversal in social mobility.

Indeed, that is one of the reasons he believes vehemently that free undergraduate university tuition should continue to be offered to all young people.

“It makes Scotland distinctive and gives the impression that the democratic instinct is still alive – that’s very important,” he says. “When I went through university we got subsistence and travel allowances, too. I simply cannot countenance behaving in a different way with the current generation. They are living in a very difficult world. We, the baby boomers, owe them.”

Indeed, when I ask whether he is optimistic about the future, he shakes his head sadly, while conceding he has always been a “glass half empty” man. But this pessimism is clearly down to circumstance as well as personality.

“The fact that someone like Trump could be elected by the most powerful nation on earth is a fearsome metaphor. Then you go to Westminster and find the most maladroit UK government since the mid-19th century.”

Then there’s Brexit. At the very mention of it he grows agitated. We both laugh out loud, however, at the absurdity of my asking what he thinks will happen in the coming months.

“The future is not my period,” he answers. “But two months after the Brexit vote I said it wouldn’t happen. And I think the chances of it not happening are now greater than ever. I’m not saying it’s more than 50 per cent but there are possibilities. It will be a disaster for Scotland – indeed for the UK – if we have to leave without a consensual agreement.”

The possible ramifications for Scotland’s constitutional position are not lost on the scholar, who wrote widely about and voted in favour of independence in the 2014 referendum. He has not changed his mind.

“The irony, if Brexit did happen, especially with no agreement, is that it would be a vital force in making for a new vote for independence. If [no deal] didn’t happen, it would be much more difficult to mount a challenge to the union.”

And does he have any words of counsel for First Minister Nicola Sturgeon as pressure mounts from more eager elements of her party and the pro-independence movement for another referendum as soon as possible?

“If one could suggest advice to someone with so much responsibility, I’d say keep the powder dry until the situation with Brexit is known and make extensive preparations in private or a secluded way to prepare for a possible referendum,” he says. “We saw that in some ways with [former MSP Andrew Wilson’s] intellectually honest growth report.

“But if there is an attempt down this route over five, 10, 15 years and it failed, there won’t be another one for a very long time. There’s a much higher threshold of risk for the second attempt.

“I feel it is impossible to have a consensus on this in Scotland – if there is a vote in favour of independence there will always be a very considerable bloc of people who are pro-union and cannot be shifted.”

Will he see independence in his lifetime? “No, I don’t think so.”

So what’s next on the agenda, other than enjoying time with his wife of 48 years, Catherine, their four children and eight grandchildren?

“I want to write something, but I’m not sure what it is. I could be a spent force. I’ve been writing about history for 48 years and, as someone once said about a variety of things ‘that is not sustainable’.”

He lets out a mischievous laugh and one gets the impression he already has something up his sleeve. We’ll see. No matter what he does, I can’t help thinking his grandad would be very proud.

The Scottish Clearances: A History of the Dispossessed, 1600-1900 is published on October 2, priced £25 in hardback by Allen Lane.

Sir Tom Devine will launch the book at an event in St Cecilia’s Hall, Edinburgh, at 6pm on October 06.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel