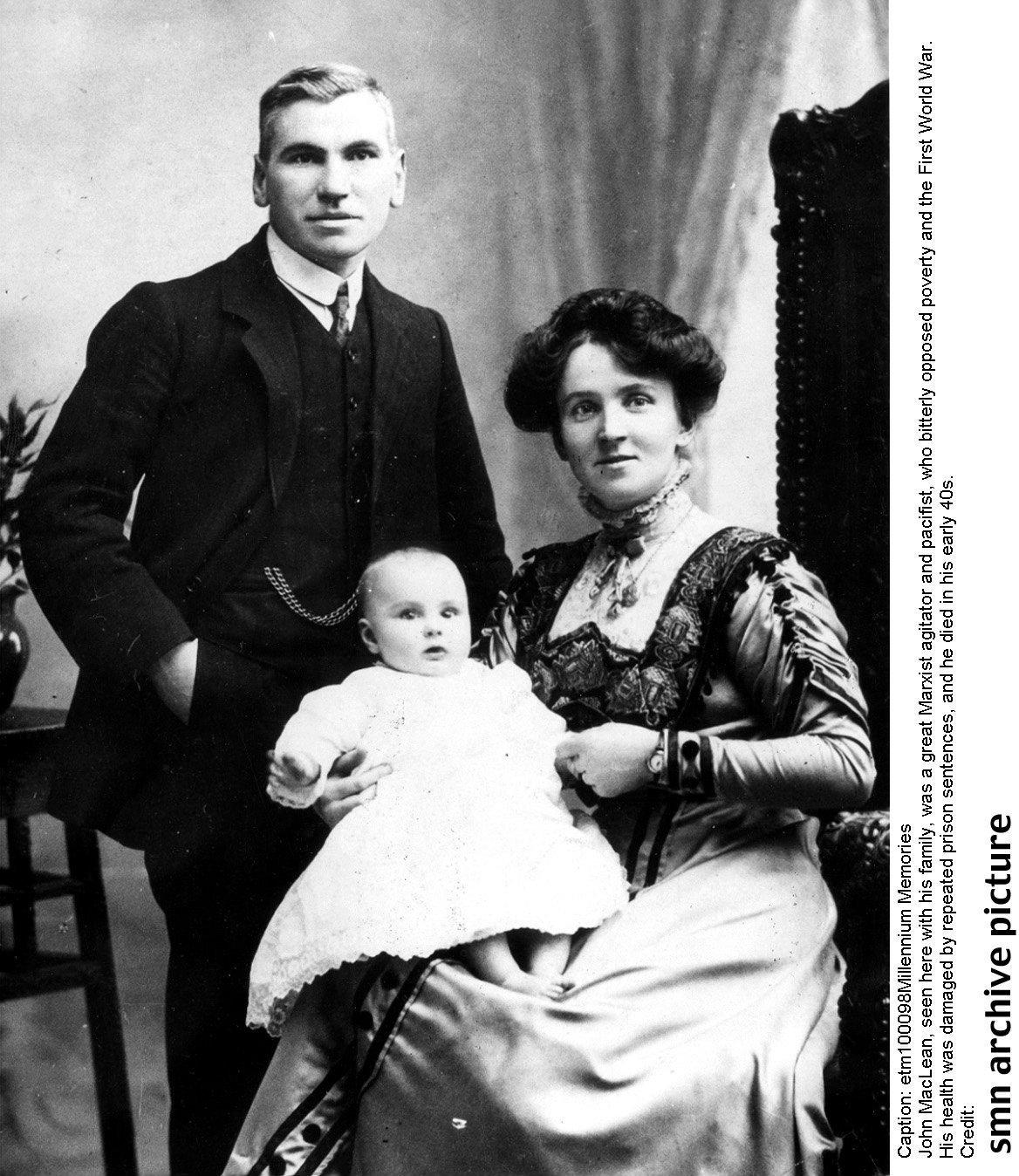

A CENTURY ago yesterday, the revolutionary socialist John Maclean, “looking fairly well though slightly worn in appearance”, stepped off the train from Aberdeen at Glasgow’s Buchanan Street station.

Maclean had just been released from Peterhead Prison, seven months into a sentence of five years’ penal servitude for making speeches in contravention of the Defence of the Realm Act - sedition, in other words. It was his second term of imprisonment in the space of a few years.

In his appearance at the High Court in Edinburgh in May 1918, Maclean - who earlier that year had been appointed by Lenin as Bolshevik consul in Scotland - made a remarkable speech to the jury, saying he stood before them “as the accuser of capitalism dripping with blood from head to foot.”

He was met by a “large number of supporters” on the station platform, including such well-known names as Willie Gallacher, James Maxton and Neil McLean. They struggled through a crowd of wellwishers to convey him home.

In Buchanan Street, the Glasgow Herald reported the following day, several thousand supporters greeted Maclean enthusiastically and followed him all the way home to Pollokshaws, singing The Red Flag en route. He declared that his revolutionary spirit was as strong as ever.

Yesterday, one hundred years to the day, part of the march from Buchanan Street to Carlton Place, near Jamaica Bridge, was retraced as far as possible by a group of marchers celebrating the centenary.

A Facebook post on the new march says that a crowd “well in excess of 100,000” gathered outside the Buchanan Street rail station on December 3, 1918. By the time it arrived at Carlton Place it had swollen to twice that size as feeder marches arrived from Parkhead Forge and the Singer factory in Clydebank. “At this precise moment,” the post adds, “Glasgow was the centre of the world. And John Maclean had put it there.”

“It went extremely well,” said co-organiser, Alan Smart, who describes himself on Facebook as a “social justice campaigner, songwriter and street musician” and creator of the website www.johnmaclean100.scot.

“The whole march had to be organised at the last minute when we realised that nothing had been done to mark the centenary. There were two or three of us, musicians, who held a concert in the Mitchell Library then belatedly thought of holding a rally as well.

“We had no idea about the numbers but it was never about that. We were pleased with the numbers who did show up, however. We were lucky that Arthur Johnstone, who’s world famous for singing the John Maclean March, turned up and closed the event by singing that song and others.

“We had a couple of young women who were maybe in their early twenties who came all the way from Dunfermline because they had learned tales about Maclean from their father. They went away absolutely chuffed. The whole event had a real feel-good factor.”

Mr Smart said that when Maclean was despatched to Peterhead “it was the equivalent of sending him to Siberia. It was the toughest prison. He was a teacher, a middle-aged man, and not one of the criminal classes. But they tried to break him, and he went on hunger strike, and they force-fed him. It affected his physical and mental health. In truth, he wasn’t the same man afterwards. On the day he came out, even his best supporters knew he was a shadow of the man who had gone into prison.”

Asked why it was important that people remembered Maclean, 95 years after his death in November 1923 at the age of 44, Mr Smart said: “The Maclean message remains, to my mind, as dangerous and as challenging to the political establishment. I’m not talking about the Tories here, but about Labour and the SNP. I think he’s too nationalist for the Labour Party and too socialist for the SNP, so they both shun him. The reality is that he is miles ahead of any of them and that he is a giant of all time. He’ll remain a giant of all time. He was the most famous political prisoner in the world in 1918. The security services of the time labelled him as the ‘most dangerous man in the British Empire’.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel