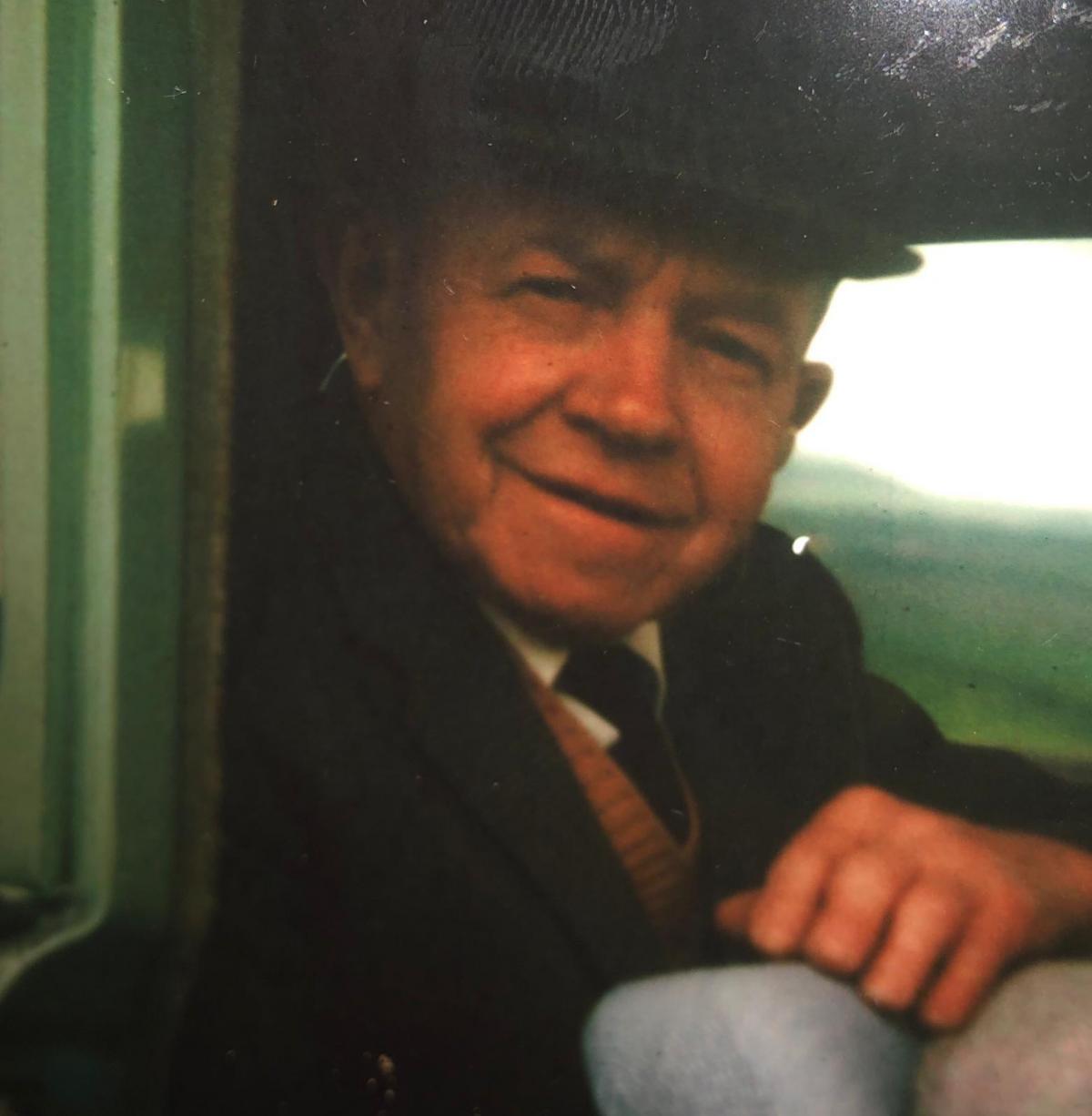

THE late Tom Weir used to speak about his memories of growing up in Springburn, the railway capital of Scotland. His mother was a carriage-painter in the Cowlairs works of the North British Railways, and he remembered her coming home with streaks of paint on her face and her work overalls.

As a milk boy of 12 he was often swept up in what he once described, in an STV interview, as the “avalanche of men that poured down Springburn Road every morning at half past seven, answering the [factory] horns… If your hands were full of milk cans, you had to be off the street or be swept into Hyde Park works whether you liked it or not.” Twenty-seven thousand people lived in Springburn when he was young, all of them engaged either in the building or servicing of locos, or working in the Co-op.

Many thousands of locomotives were built at Springburn - at Cowlairs, at the Caledonian Railway works (the 'Caley'), at the North British Locomotive Company's works - over the decades. As John Thomas puts it in his 1964 book, The Springburn Story, “the good folk of Springburn were well used to the spectacle of out-of-gauge engines trundling down Springburn Road in charge of a pair of snorting traction engines, bound for some sun-baked railway halfway round the world.”

Today, however, Springburn, has little left of that remarkable heritage, save the St Rollox works, which were opened in 1856.

Labour MP Hugh Gaffney’s grandfather, Walter Freer, worked there in the 1920s. “He lived in Springburn with his family and it was clear that St Rollox was the beating heart of the community,” Gaffney says. Once, when his wife became ill with multiple sclerosis, the management granted him a period of compassionate leave until the family could make arrangements to look after her. Gaffney also relates an occasion when Walter was attacked while heading home from work one day; he carried a little case which he used as a piece-box, but which his attacker thought contained money.

“Many of those who worked at St Rollox also lived in Springburn, which fostered a great sense of community spirit," the MP adds. "My grandfather loved his job and it enabled him to provide a good life for his family. He was a small man but with a big heart, and he always reserved a special place for St Rollox within it.”

Over the subsequent decades, St Rollox has shuttled from owner to owner: London, Midland and Scottish Railway, British Rail (latterly under its subsidiary British Rail Engineering Ltd); Babcock International/Siemens, Alstom, RailCare, Knorr-Bremse, then Mutares. But now it faces closure, and Springburn is in shock. To quote from information placed before MSPs at Holyrood: “Mutares announced the closure of the works in December 2018. In recent years, staff at the works have focused on rolling stock and component refurbishment."

At risk are some 180 jobs: a workforce of 120 plus around 60 agency staff. St Rollox specialises in handling older rolling stock. The Scottish government has expressed disappointment that it only found out about the closure from the media.

A 45-day consultation period was launched on January 17. The Unite union launched a campaign, Rally Roon the Caley, demanding Network Rail carry out electrification to link St Rollox with the nearby Glasgow-Edinburgh rail line at an estimated cost of less than £1m. A spur from the flagship rail line would enable the depot to explore diversification, Unite believes.

It also wants the Scottish Government to bring the depot under its control "as an asset of strategic importance in Scotland’s transport infrastructure.” Unite says this demand is based on the precedent set by the Scottish Government when it brought Glasgow Prestwick Airport under its control in November 2013. As of Thursday morning, the campaign has attracted 2,293 signatures.

Read more: Closure of historic Glasgow rail repair plant with 180 jobs at risk 'will send work to England'

Gemini said last month that the consultation period, which is scheduled to end on March 4, would permit the exploring of options with a view to avoiding redundancies. A spokesman said: “The proposal [to close] is as a result of increasingly changing and challenging market conditions which are outside of our control. It is very clear, as it has been for some time, that numbers of pre-privatisation rolling stock which have been the cornerstone of business for many years, are in severe decline.

“Due to the introduction of more modern vehicles, the number of pre-privatisation vehicles in service will reduce by 80% in the next five years. Furthermore, Springburn will continue to suffer an unsustainable decline in demand, due to its location, as only around 10% of the rolling stock that will be accessible is in Scotland and the North of England. As such, it is necessary to put forward the proposal. The decision to make this proposal has not been made lightly.”

To Bob Doris, SNP MSP for Maryhill and Springburn, the potential closure is a “devastating” blow for the workforce, local communities and the locomotive industry. To the rail union RMT it is "an act of industrial vandalism that will not go unchallenged”.

James Kelly, Scottish Labour and Co-op MSP for Glasgow region, who hosted a debate on St Rollox at Holyrood in midweek, believes government intervention is needed to save the jobs and the plant. Hugh Gaffney says: “It would do a disservice to the proud history of generations of St Rollox workers for it to be closed, and would strike a blow to the community of Springburn”.

Pat McIlvogue, the Regional Industrial Officer at Unite the Union, who is responsible for the works, says the union campaign has attracted “huge” support not just from across Scotland but also from South Africa, Canada. “The uniqueness of St Rollox is that it has history and heritage all around the world,” he says. “It has been a cornerstone of engineering here for 150 years. The depot is highly skilled and efficient. It’s the biggest depot for rail maintenance in Scotland.

"Mutares has told us privately that it wishes it could take the Springburn depot and replant it in England, because they have decided that they don’t want to be in Scotland. But the skills, the knowledge, experience, the quality of workmanship, and the affinity that people have with the site, are all way above the average.”

The union believes that with “a bit of forward thinking” there could be a long-term future for Springburn. It urged Gemini not to impose the 45-day statutory notice but to instead work to find a way to “key stakeholders” to put together a feasible rescue plan.

The union queries the £1 million loss that Gemini says it has made at Springburn and Mr McIlvogue says in a Facebook video post: “We believe that with true management that that loss can … be turned around.”

He says the depot has enough work on diesel rolling stock to keep it open in the short to medium term; electrification would give it access to two-thirds of the Scottish rail stock and thus prolong its lifespan.

Paul Sweeney, Labour & Co-op MP for Glasgow North East and a Shadow Scotland Office Minister, was quick to involve himself in the crisis, meeting a director of Gemini Rail Services, owners of St Rollox and a subsidiary of Mutares.

His mother’s uncle Jimmy was an employee at St Rollox in the 1960s and 1970s. “She used to tell me about him working there as a wee boy,” he says.

That’s the thing about St Rollox, he adds. “Even now there are only 200 people working there now, there are thousands of people, still alive, who’re associated with the place. That’s why it has maybe punched above its weight for a normal factory with 200 workers. It has a bigger hinterland, a bigger community around it.”

That community has suffered, though. Over the years, the decline of Springburn and the loss of some of its fine old buildings have prompted much anguish. “Historic Springburn was literally sliced in half in the 1960s by wholesale demolition of good tenement buildings for the construction of the A803 road,” writes Ian Mitchell in his updated book, Glasgow’s Industrial Past. The road damaged Springburn, Mitchell says, even though it was not built for its inhabitants. It forcibly divided one half of Springburn from its shops and facilities. Similarly, there’s little physical evidence of the once-mighty presence of the area’s rail works.

“The St Rollox site once took in the whole area that is now the Royal Mail Sorting Office, Costco and the Tesco,” muses Paul Sweeney. “It has been downsized quite substantially since the 1980s. At one time, at its peak, there were 15,000 people involved in the locomotive industry in Springburn. It was a huge industrial concern, just as shipbuilding was.

"People think that the Finnieston Crane [near the SEC Campus] was built to serve the shipbuilding industry but in actual fact the bulk of its work was lifting the big steam locomotives onto ships.”

In a speech that began not long before 2am on January 14, Sweeney told the Commons that the Caley works had existed since the dawn of the railway age, and that, during the Second World War, it turned out Airspeed Horsa gliders for the Normandy landing airborne assault of D-Day in June 1944. “It is very sad that we could be witnessing the end of an industry that is synonymous with the community of Springburn in which it was built.”

In his view now, St Rollox has in recent years “gone through a succession of private owners. It has always been in a bit of a precarious situation; it has been passed from various different owners.

“What has happened is symptomatic of some other Glasgow industries. They become branch plants, so that the ownership and the management decision-making is no longer in the city. The entrepreneurial drivers aren’t in the city any more, so they’re basically at the mercy of decisions that are made in boardrooms far away from Glasgow.

“That’s the key problem with what’s happened at Springburn. The main headquarters of what’s known as Gemini - until a few months ago, Knorr-Bremse - is at Wolverton railway works in Milton Keynes. The vast majority of the staff, all of the decision-makers, all of the white-collar staff, are all based there. And even though that site is under-performing relative to Springburn, they still decided to shut Springburn and concentrate their operations at Milton Keynes.

“So our view is, this is not just a fight to save the heritage of locomotive engineering in Springburn. It’s also about trying to re-establish an entrepreneurial spirit for the locomotive industry in Glasgow.

“The Reid family were the big entrepreneurs behind the North British Locomotive Company [it was created in 1903 through the merger of three locomotive manufacturers, and became a industrial colossus]. If you look at their huge headquarters building on Flemington Street in Springburn, you can think of the wealth and the ambition that were once there in Springburn, a century ago. To think it has now been whittled to its last gasp is quite sad.

“Part of the problem is not just the issue about keeping the works open - it’s actually, ‘let’s create a platform from which we can grow the industry again’. There’s huge potential for engineering. Look at Allied Vehicles in Possilpark - it has grown from nothing to having 500-odd employees. That’s because there’s been local entrepreneurialism, local management, local decision-making leading it. My feeling is that with the right sort of restructuring, St Rollox can have that sort of prosperous growth ahead of it.”

Read more: Glasgow's St Rollox train yard rolls into history

Daryl Steel, 44, a maintenance fitter/electrician, has worked at Caley for 28 years. He followed in the footsteps of his father and his grandfather. His dad was a production manager years ago, in charge of around 1,000 people. “Quite a lot of us older guys have had family members who worked at the yard,” is how he puts it.

“The skills base that will be lost if the depot closes will be incredible. You will never be able to replace it. I feel Springburn is being shafted to preserve the English workforce [at Wolverton]. The English depot is a shambles and it’s responsible for 90 per cent of the losses that the company is making.

“Since the yard was privatised no company has run it for more than five years,” Steel adds. “What we’re hoping for is the Scottish government to intervene, because otherwise the majority of ScotRail’s older fleet would need to be repaired in England.

“All you’re talking about is a mile of overhead electric line to put us onto the main Glasgow-Edinburgh line,” he adds. “The amount of work that that could bring in … It could be another shed that ScotRail could use for storing its vehicles and doing overnight examinations in addition to the existing Eastfield depot. The guys in our place, although they’re traditionally doing heavy maintenance and overhaul, could quite easily adapt to any other kind of railway work.”

Derek Hearton, 53, is now in his 37th year at St Rollox. What does he think of the potential closure? “I think the writing’s been on the wall for a few years, to be honest. Between us and Wolverton, Wolverton has been making huge losses. Obviously, we were in administration five years ago. I thought when the German company came in they would have turned it around, but they didn’t really do what they said they were going to do.

“It’s unfortunate what has happened to St Rollox, because it’s a good site, and it’s a great place to work. But now we think there’s no chance. But that’s the thing - we’re still putting the jobs out on time, we’re still doing really well, and they guys are still all working to the end. They haven’t given up.”

Last Tuesday, Transport Secretary Michael Matheson, who chairs a stakeholder group which aims to save St Rollox, told Holyrood that it was "disappointing" that the company had taken the approach they had. They had, he said, refused to postpone or delay their consultation exercise despite representations.And once again, he called upon Gemini to delay any decisions over St Rollox to allow work to be done to save it.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here