THE NIGHT before we speak, Francis Rossi tells me, he had a dream about Rick Parfitt. There have been a few of them down the years since Parfitt, his long-time friend and fellow Status Quo member, died in 2016.

In the dream he and Parfitt are in Harrods, dressed to the nines and heading to the top floor where there is some kind of do on. They are surrounded by people who were rather more toffee-nosed than members of Status Quo ever really aspired to being, Rossi explains.

Turning to Parfitt, Rossi recalls, “I suddenly say to him, ‘I thought you were dead, weren’t you?’ And he says, ‘Yeah, I know.’

“And then these other people said, ‘I thought he was dead.’ And I said, ‘Well, yeah, but that’s Rick, innit.’”

Francis and Rick. Death hasn’t separated them. Not quite. Not yet.

February and Francis Rossi, 69, is at home munching on a sandwich made by his wife Eileen. “My wife is American. She calls it a grilled cheese sandwich.” He pauses a beat and then puts her right. “It’s fried.”

Rossi has a new book, I Talk Too Much, a memoir, to promote. And a tour. But, really, he’s just happy to talk about anything that comes up. In conversation he’s like his band; head-down, straight-ahead, no-nonsense. Well, mostly.

But, now and then, he goes off at a tangent, following an idea or an image that appeals to him.

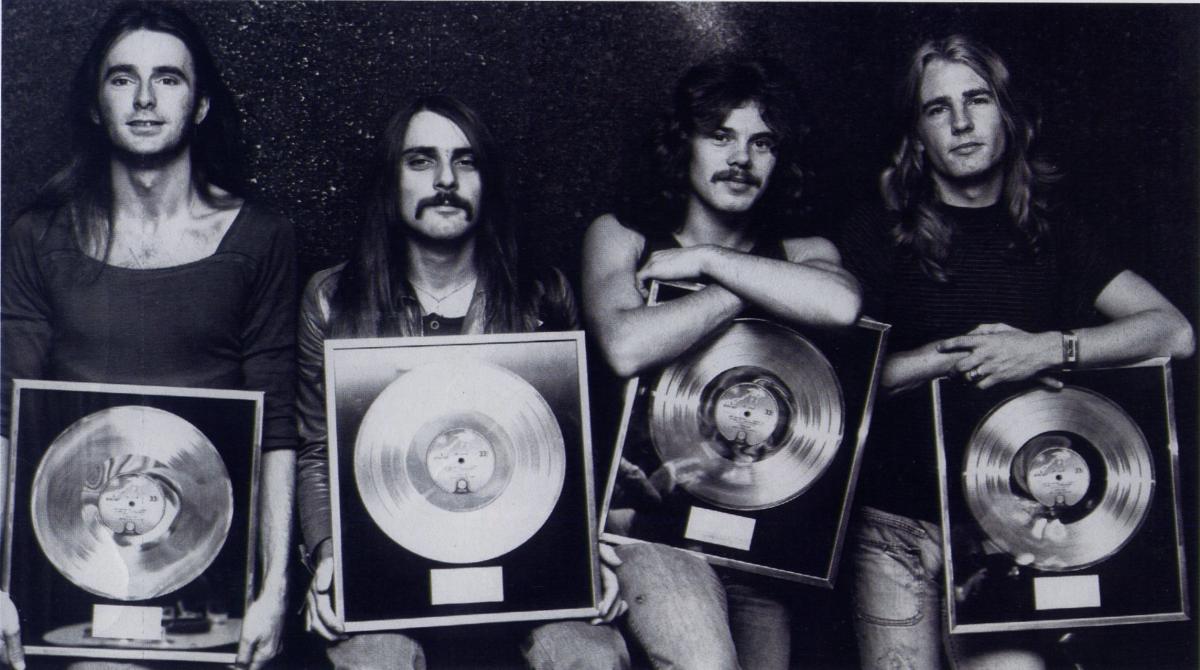

He is not short of things to talk about. Because the Status Quo story is not just the story of one of the biggest bands in British rock; more than 100 million record sales and 65 hit singles stretching back to the 1960s. It’s also the story of friendships that went sour, interband rivalries, and groupies. (“In the current MeToo climate,” he writes of the latter in his book, “this has become a tricky subject to try and explain.”)

“There were certain stories in there where you think, ‘Ooh, I’m not sure …’ I was talking to my daughter yesterday and thinking ‘whoops.’ But they know who their dad is,” he says this morning.

And it’s the story of opening Live Aid while barely being able to stand up. (“I was so coked I could barely see the guitar in my hands” Rossi admits in I Talk too Much)

In short, it’s the story of too many drugs and too much denim and the odd Platinum disc.

And, inevitably, it’s the story of his relationship with Parfitt, who he met while performing at Butlins in the early 1960s and spent the next 50 years with in the band, for good and bad.

As early as the second page of I Talk Too Much, Rossi writes, “I loved Ricky and I still do. He sent me bonkers a lot of the time and he still manages to do that too. He was everything that I wasn’t and used to wish I could be: flash, good looking, talented, the glamorous blond – a real rock star, in the truest sense.”

This morning Rossi adds, “I’ve been as honest as I can about Rick. Obviously, there were things about him that were fabulous. We had a fabulous time together. It went sour before the end. There were reasons which weren’t necessarily his fault.”

We’ll come to that. But to start at the beginning, Rossi was just 16 when he first met Parfitt. At Butlin’s of all places. Rossi and his schoolmate Alan Lancaster’s band, The Spectres, had been booked to play the holiday camp in Minehead in Somerset.

Rossi’s first impression of Parfitt? “We thought he was a faggot, poof. All those words you’re not supposed to use anymore. What do you call them? Gay, sorry. They’re not all gay, actually. They are not all jolly.

“There are so many camp people and I love camp people. My son is a homosexual. So, when I first met Rick he was very much in that side of showbiz. He used to mince a lot. And to us, that was fun and somewhat escapist from the [idea that] ‘You’ve got to be f****** macho because you’re a bloke and you’ve got bollocks and hairs on your chest.’ Know what I mean?”

When Parfitt finally joined the band, Rossi followed his lead and played the campiness. They’d hold hands just to freak everyone else out.

Back then, Rossi says, he was both insecure and cocky. Parfitt offered him a model of who he would like to be. Rossi had grown up in south London, the son of an Italian ice cream seller and an increasingly religious mother who came from Irish stock in Liverpool. Obsessed by pop music - he loved the Everly Brothers and eventually The Beatles - he had formed a band with Lancaster. The gig at Butlin’s Holiday Camp was where Rossi met both Parfitt and his future first wife Jean Smith.

Knowing just how huge the Quo were to become through the 1970s and 1980s it’s difficult to imagine there was a time when success was anything but inevitable. Through 1960s the band continually changed their name and released singles and no one much cared.

They became Status Quo in 1967 and released the single Pictures of Matchstick Men at the start of 1968. Parfitt joined the band while they were recording it. Finally, they had a hit.

The problem was the song was psychedelic as was in fashion at the time, but Status Quo were a rock band who were performing a set that was influenced by the big soul voices of the time: Wilson Pickett, Sam and Dave. “I was thinking, ‘I don’t know what I’m doing? I’ve got no idea.’” Rossi admits now. In short, the Quo didn’t really make sense at that point.

It took them to go back to basics to find themselves again as the seventies kicked off. “We went back, ditched the clothes and went back to wearing what we could frigging afford and that became an image.

“I remember this girl Val Mabbs who was a well-known writer of the time. She used to knock back pints of Guinness at lunchtime. Christ, she was keen. In 1971 she said, ‘I love your new image.’ And I thought, ‘I’m not going to say anything. I don’t know what she’s talking about.’”

Denim wasn’t cool at the time. You couldn’t get into clubs wearing denim. “I’m pretty sure you couldn’t get into the cinema,” Rossi says. But that became the band’s image. “I think Lancaster even had a pair of denim high-heeled boot things. Well, he was short, weren’t he? Little sod,” he adds, laughing.

By the end of 1972 the newly bedenimed Quo were in the top 10 with the single Paper Plane and the album Piledriver. They were finally the rock stars they had always dreamed of being.

Turned out the reality didn’t quite match up to their dreams.

“With the band it was us against the world. It’s all going to be great when we get there. Alan Lancaster used to sing ‘Hi ho, hi ho, we are the Status Quo. When we’re number one, we’ll have some fun. Hi ho …’ And then when we got there it was, ‘F***, this is hard work.’”

For Rossi, success wasn’t the panacea he’d been hoping for. “I thought, ‘I wouldn’t argue with the wife. I thought my mum and dad would be happy and la, la, la life would be idyllic.’

“And I remember after Top of the Pops, the second one I think, waking up in the morning and thinking, ‘Well, nothing’s f****** changed. I’m still that bloke! I still get on my tits. My wife still winds me up. My mother-in-law still gets on my tits.’

“Whatever it was, one’s mundane life never changes. But showbiz life has this lovely façade, which I suppose it should have. But mouthy people like me keep trying to tell people that, ‘Nah, it’s not quite what you think.’”

Rossi chews his fried-not-grilled cheese sandwich and then offers up an unlikely visual metaphor for fame.

“You know that hospital gown. The one they have that people walk towards you and you think, ‘He looks covered.’ And then you look at his back and his bum’s hanging out? That seems to be showbusiness. Its arse is hanging out. And you don’t want to see that crack at the back there.”

Of course, when success doesn’t fill the void, you turn to other things to try and do it instead.

By the 1980s Rossi was in a dark place. The band was falling apart. (They split in 1984, reformed in 1986 for Live Aid). There were arguments, members were leaving in bad blood and Rossi was drinking too much, taking too many drugs. The evidence was in plain sight. On their 1980 hit Just Supposin’, Rossi sang the line “I might be runny runny runny runny nosin'.”

There was no “might be” about it.

“My first wife, I remember her saying it was beginning to change my personality. ‘No, it f****** ain’t.’ Well, of course it was. I became a drinker, a loudmouth in bars I suppose. It’s the alcohol that gives you that kind of brash behaviour which led me to coke. I would never have touched the coke if I hadn’t been drinking.”

That was the guy who writes that he can’t really remember 1983, a year he passed in a coked-up, booze-dampened blur. This was the guy who could barely hold his guitar at Live Aid. This was the guy whose septum famously fell out while he was taking a shower in 1987. In the book he describes said septum as looking like a “a chunk of chopped liver on the floor of the shower.”

Francis, I say, can I ask you about that day? You say in the book your manager told you to pick it up and take it to the doctor. What I want to know is what did the doctor say to you when you did?

“I don’t remember,” Rossi admits. “I don’t remember if I took it there or not. To be honest … This is gross … It was a scab of some sort. My nose had been bleeding and every time a scab came off, I thought, ‘That’s good, lovely,’ forgetting bits of nose were going with it.

“Oddly enough,” he continues, breaking off at a tangent, “my daughter lives in Canada. I was speaking to her yesterday on FaceTime. She works in a PR company and the girls were going, ‘Oh, is that your dad? Yeah? Show me the cotton bud trick.’

The cotton bud trick, if you don’t know involves putting a cotton bud up one nostril and pulling it down the other. An advantage of the absence of a septum.

“So, I had to show this woman the cotton bud trick. I said, ‘Any coke in the office?’ They both looked guilty. I said, ‘Then this is what can happen.’”

The days of drink and drugs are long behind him now, of course. “I’ve gone back to being such a boring shit. Today I think I finish at two. I will go into this room where I have a log fire and sit and do jigsaw puzzles. And I will do those until I have to go back out on the road.”

The problem in the latter days of the Quo was that while Rossi had calmed down, his mate Parfitt had not. He still wanted to play the rock star, didn’t want to, or just couldn’t, give it up. His behaviour became increasingly a problem.

To Rossi certainly. “He was almost defiling the man I loved originally. I don’t mean that to sound hammy. It was kind of a let-down.”

Parfitt was still partying hard, and then taking drugs to come down, drugs that weren’t necessarily helpful, Rossi suggests.

“He used to take various sleeping tablets. One was called Rohypnol, which they call the rape drug.” As a result, he says, Parfitt would often not know what he’d done the night before.

“He genuinely had no idea. I would still be getting over what he did or said the night before to whomever and he was oblivious. ‘What’s the matter with him? What’s wrong with you?’”

Parfitt wanted to be a rock star. Flash cars, flash women. Rossi wasn’t bothered anymore. “So, we were getting continually further and further apart.”

Now and again he’d see glimpses of the old “Ricky” he knew. “He’d be lovely. You’d see it in his face. You’d see it in his eyes. The whole rock ’n’ roll mean pout would go. So, either he was feeling shite for the amount of things he’d done the night before or …I’ve no idea”

In June 2016, Parfitt had a heart attack after a show in Turkey. Rossi and the rest of the band thought he was dead. Six months later he was. Rossi got the call on Christmas Eve. A friendship and a musical partnership that had lasted 50 years was over.

Do you think he realised how much he mattered to you, Francis? “Probably not. It’s difficult to tell.”

Life goes on. Musicians play gigs because that’s what musicians do.

Music, Rossi says, is one of the few things that can make him cry. What I ask was the last piece of music that moved him to tears.

He tells me a story about sitting on the bus at the end of his last tour. He was suffering from pneumonia and had just had to cancel gigs. And for some reason he put on All the Reasons, a track Parfitt had written with Alan Lancaster for that 1972 Quo album Piledriver, one of the band’s least rock and roll moments.

Listening to a song written back when the Quo were just beginning to become the Quo, Rossi tells me, he had a bit of a moment.

“People said I didn’t cry for Rick and I didn’t. I didn’t cry when my mother died. I didn’t cry when my father died. I don’t know why. We weren’t ever that way. It’s almost like an exhibition. We won’t do that.

“But there I was, and I welled up. ‘Oh, there’s Ricky.’”

In the end life is a catalogue of losses. Francis Rossi knows that all too well.

I Talk Too Much by Francis Rossi, is published by Constable, £20. An album We Talk Too Much, recorded with Hannah Rickard is out now. Rossi’s spoken word tour I Talk Too Much is at the Albert Halls, Stirling on Thursday, the Grand Hall, Kilmarnock on Friday, the Carnegie Hall on Saturday March 23 and the Beacon Arts Centre, Greenock on Sunday, March 24.

Why are you making commenting on The National only available to subscribers?

We know there are thousands of National readers who want to debate, argue and go back and forth in the comments section of our stories. We’ve got the most informed readers in Scotland, asking each other the big questions about the future of our country.

Unfortunately, though, these important debates are being spoiled by a vocal minority of trolls who aren’t really interested in the issues, try to derail the conversations, register under fake names, and post vile abuse.

So that’s why we’ve decided to make the ability to comment only available to our paying subscribers. That way, all the trolls who post abuse on our website will have to pay if they want to join the debate – and risk a permanent ban from the account that they subscribe with.

The conversation will go back to what it should be about – people who care passionately about the issues, but disagree constructively on what we should do about them. Let’s get that debate started!

Callum Baird, Editor of The National

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here