ONE of the entertaining stories in Bill Innes’ new book concerns a farmer’s large collie that was once put into the hold of an Islay-bound British European Airways Rapide airplane at the old Renfrew airport.

En route to his destination, the pilot began having difficulties in controlling the small plane. The Rapide was a 1930s design – essentially, a wooden framework covered in a fabric that had been coated with a plasticised lacquer.

The pilot was able to land safely at Islay where the source of the problem became clear. The dog had escaped from his crate and chewed his way through the side of the hold. On the plane’s final approach, Innes writes, the collie was seen from the ground, “sitting with his head out of the side of the fuselage, ears pinned back by the blast, contentedly admiring the scene…”

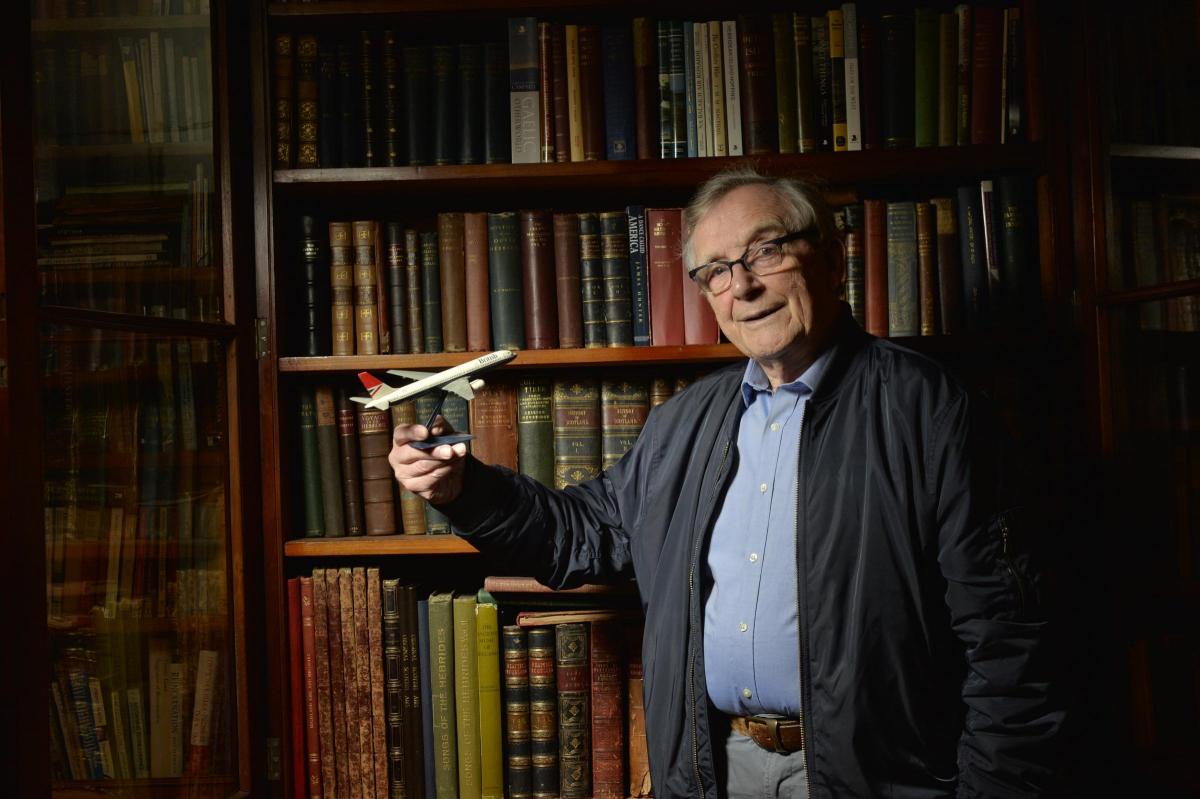

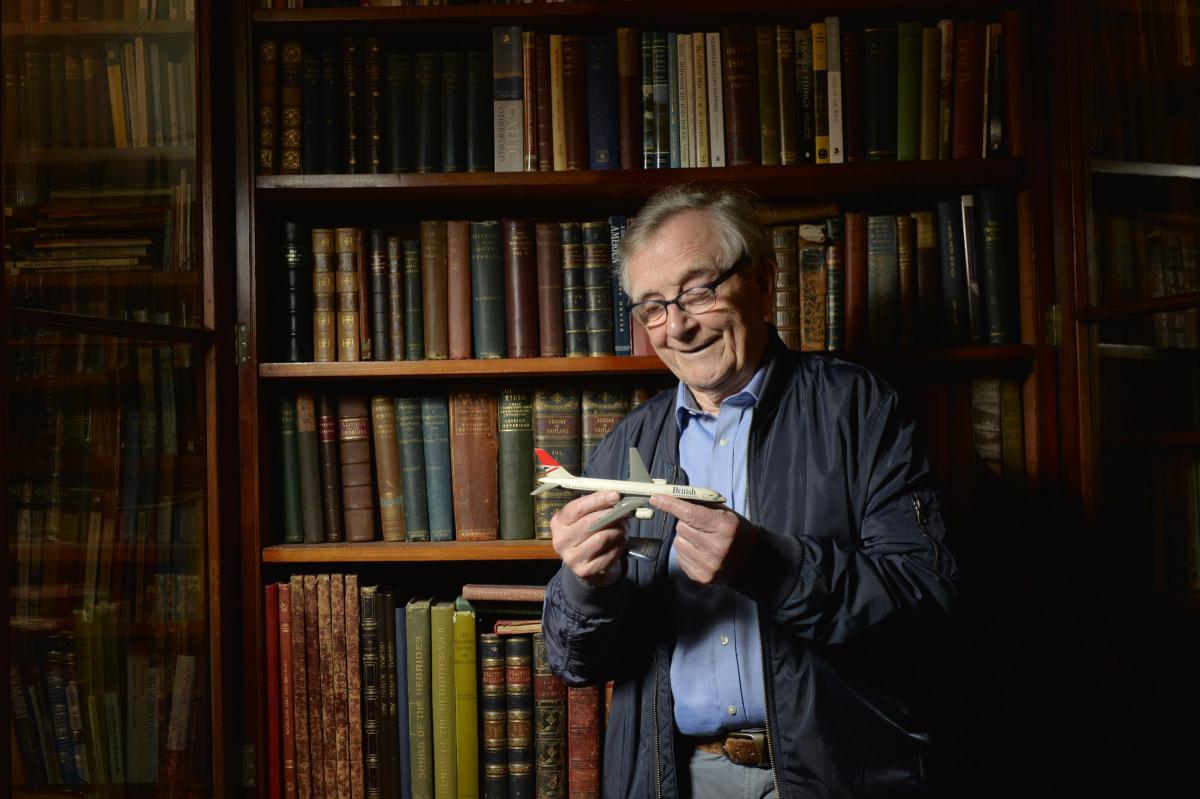

The book, Flight from the Croft, is a vivid and nostalgic look at Bill’s long career in early commercial aviation in Scotland. The very planes – the Caravelles, the Comets, the Viscounts, the Vanguards, the Tridents – have an evocative magic of their own. He remembers the deHavilland Comet 4b as being arguably the most beautiful commercial jet of all time. “Those of us flying it at the time,” he says, “just thought it was the best aircraft in the world.”

Bill Innes is now 85. As a pilot, he saw it all, from Cold War-era Berlin to Beirut in the 1960s, a time when that cosmopolitan city could still be regarded as a Mediterranean pleasure-spot. In Delphi, Greece, in 1963, he and his colleagues glimpsed Jacqueline Kennedy, wife of the US president, and her sister, Princess Lee Radziwill, a mere matter of months before Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas.

“It’s a bit of a cliche, but in fact it was a different world,” he says of that era. “It was a golden era in aviation, when pilots could use individual discretion and where there wasn’t a constant bureaucracy. You weren’t having every move monitored, as is the case nowadays. The old skippers would press through, whatever the weather.”

Whereas almost every airline operation today, he says, is monitored by air traffic control, by radar, onboard recorders and the modern threat of any mishap going viral on the internet within minutes, pilots were allowed “considerably more discretion” in the 1960s.

“Some of the pioneers from the 1930s were my mentors, so I suppose I’m a link between them and the modern, all-singing, all-dancing modern aeroplanes.”

His interest in aviation was born in 1940 when, as a seven-year-old, he marvelled at the sight of a Spitfire banking as it followed the contours of Glencoe.

Later that year, however, his father died suddenly, and his widowed mother eventually succumbed to a nervous breakdown under the strain of trying to raise Bill and his brother on just ten shillings a week.

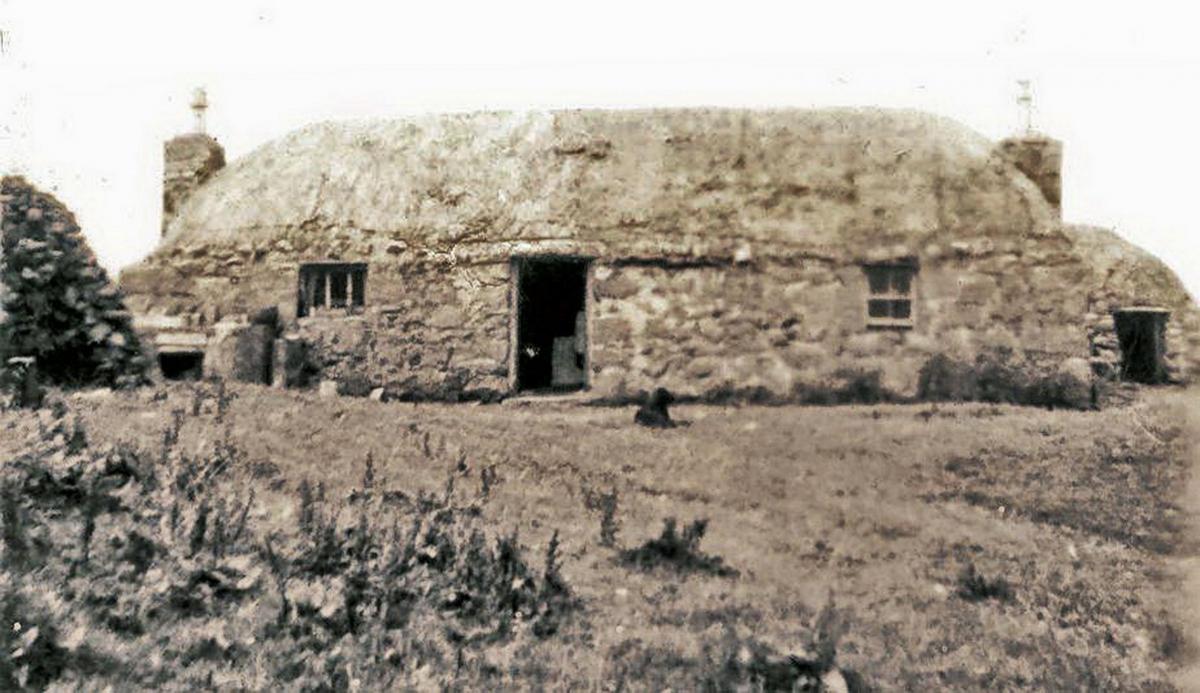

The boys were fostered to a family who lived in a thatched cottage on South Uist that did not have electricity or running water. Bill persevered with his dream of becoming a pilot, through school (South Uist then Fort William). At Glasgow University he joined its RAF reserve air squadron. He gained his RAF wings in Canada, returned home and, in September 1957, after his National Service, he joined BEA, for £10 a week.

He flew pre-war Dakotas in the Highlands and islands, where the exacting conditions were to prove an ideal preparation for his move to London, which in turn is where the classic planes – the Comet, the Vanguard – began to play a key part in his professional life.

In his time in Scotland he came, like many pilots, to have a fondness for the old Renfrew aerodrome, with its futuristic buildings. As late as 1966, Renfrew was still BEA’s main Scottish base. When Glasgow Airport, at Abbotsinch, opened in May 1966, the aerodrome buildings were knocked down.

“So many people have forgotten there was an airport at Renfrew,” he says. “Personally, I think it was a bit sad that they knocked down the terminal. It was a major architectural advance of its time. It would have been too small for modern passengers but it would have made a fine aviation museum or something like that. A council estate was built on the site of the aerodrome.”

The book reveals Bill’s sharp eye for telling detail. Turin airport, for example, lies close to the Alps; halfway through one climb, he records, “it looked as though we were heading for an impenetrable wall of granite-cored snow, shining brightly in the morning sun.” Crossing the Alps on a sunny day “could be an awe-inspiring experience. Despite the safety height giving a clearance of 2,000 feet, it often felt as though you could lean out and touch the peak.”

In the days when Berlin’s Templehof airport lay close to the boundary between the east and west of the city, landing a plane on its westerly runway gave pilots a vivid sense of the contrast. Whereas the west was a “blaze of lights and neon”, thronged with people and traffic, East Berlin “seemed like a ghost-town with dimly-lit, half-deserted streets in which only the odd car was to be seen.”

“You had to fly over the boundary, which wasn’t the Wall at that stage,” Innes says. “The contrast was stark. That’s the only word for it.”

He remembers that the Soviets made life “as difficult as possible” for western airlines; there was an ever-present threat that any aircraft straying outside the three narrow air-corridors linking Templehof with the Federal Republic might be intercepted by fighters. No flights above 10,000ft were permitted.

As for Beirut – “It was very interesting place before all the disasters in the Middle East. It was a favourite holiday spot for people from east and west. There were lots of nightclubs, hotels … There was much less aggro between various denominations in those days.”

Generally, he goes on, referring to his book, “I think it was important to record that golden era when it was still fun to go flying, when people dressed up in their best gear to get on a plane, and when the word ‘jet set’ entered our vocabulary.”

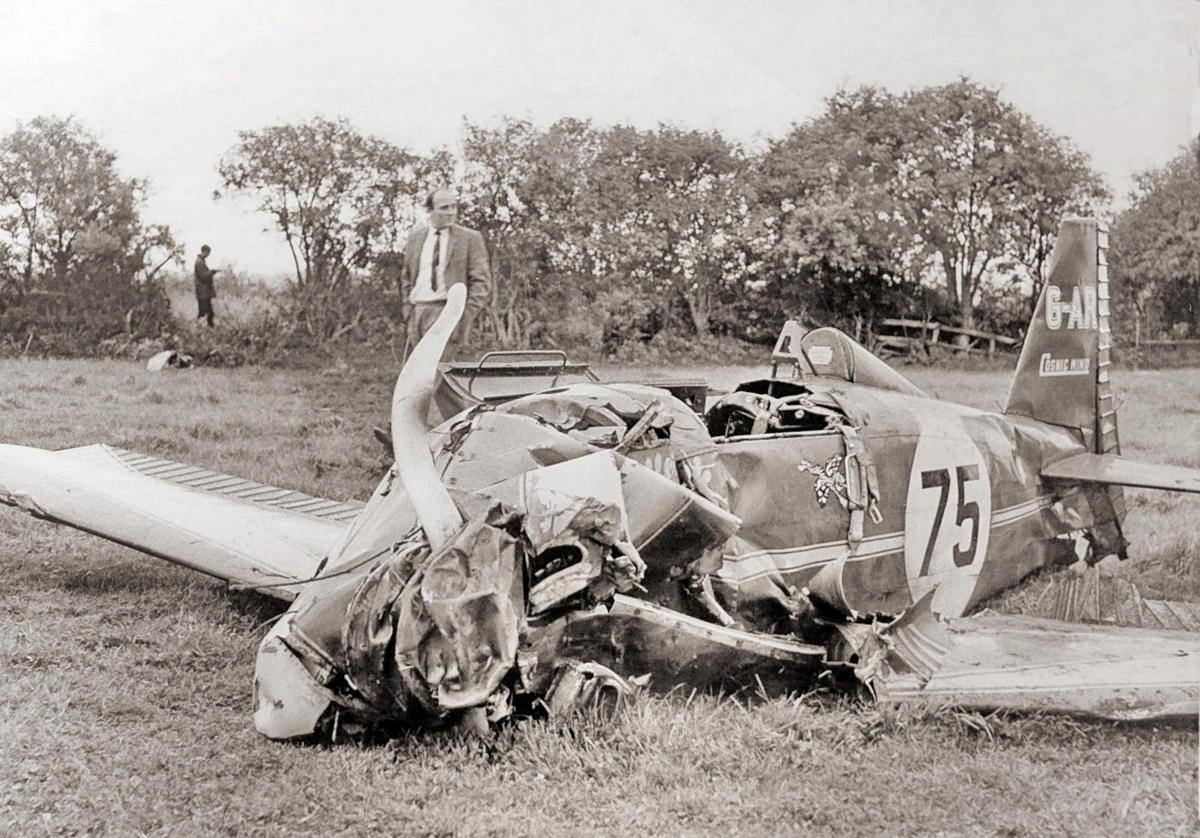

One of the most striking photographs in the book is of a LeVier Cosmic Wind – “a beautiful little racer”, in Innes’s words – in a crumpled mass after hitting the ground at 130mph at Halfpenny Green airfield, near Wolverhampton. Innes was taking part in an air-race there in the August Bank Holiday of 1966. He banked steeply into his first turn but the next thing he remembers is being pulled out of the cockpit. He suffered numerous injuries – broken tibia and fibula in a leg, a broken rib, three collapsed lumbar vertebrae. His face needed 48 stitches after smashing into the control panel.

Six years later, Prince William of Gloucester and a friend were killed in the same air-race. How did Bill himself survive? “The answer is, I don’t know. I shouldn’t have. If you hit the ground at 130mph you don’t expect to survive. But it was a very tough little aeroplane, even though it was badly smashed up. It was reconstructed, and you can still see it at the Imperial War Museum in Duxford. Basically, though, I was given an extra 50-odd years, which I wasn’t entitled to have.”

There was another close call in his career, though this one he experienced as a passenger, on board a Caravelle that had taken off from Mallorca and was cruising at 31,000ft towards the Pyrenees. Bill, having requested a cabin visit, was suddenly alerted by the captain to another Caravelle, a Barcelona-Paris flight, that had been cleared to the same level. They missed each other by a couple of hundred yards. Bill’s plane experienced a bump as it flew through the other’s slipstream.

“We were really remarkably lucky to avoid a collision,” he says. “But I’d like to stress that air traffic control is now incredibly professional. That sort of incident is much less likely to happen nowadays because aircraft are equipped with TCAS, a collision avoidance system. It will alert you to any conflicting traffic and advise the best method of avoidance."

Today, according to official figures, flying is safer than it has ever been, but the two recent Boeing 737 Max crashes, involving planes operated by Lion Air in Indonesia, and Ethiopian Airlines, led to the plane being grounded worldwide. It was reported last week that Boeing had issued changes to control systems linked to the two fatal crashes, in which nearly 350 people died. Investigators have not yet determined the cause of the accidents.

“We still don’t know exactly what happened,” Innes acknowledges. There are something like 10,000 Boeing 737s around the world, “but they have evolved so far from the original ones. This particular one, the Max, has much bigger engines, which therefore have to be pushed further forward and a little bit higher.

“With aeroplanes with engines under the wing, if you increase the power, there’s a tendency for the plane to nose up, and pilots know this. Boeing thought, because the [Max] engine was further forward, and therefore the nose-up movement would be stronger, it had better fit a system which would do something if the nose went too high.

“There was only one sensor for that system, apparently, so if that sensor misreads and it thinks that the nose is now too high, and activates a trimming system which would push the nose back down, it could get to the point where the pilot couldn’t retrieve the situation manually. That’s what the thinking is in the business at the moment, but like all these things, it is not yet confirmed.”

On another issue, Innes believes that the status of the professional pilot has been in continuous decline. In their attempts to reassure nervous fliers, pilots turned to self-deprecation with remarks such as ‘We just press the button and the autopilot takes us there’ and ‘The computer tells me we will be arriving at xx hours’. They have tried to downplay the nature of the job, he says, and such comments, he says do “scant justice” to the endless hours of training, checking and experience that airline pilots have to put in, to say nothing of their regular competency checks on highly sophisticated simulators.

“In the days when people could enter the cockpit, you’d get quite educated, middle-class people, businessmen, saying to the pilots, ‘You guys must be bored out of your mind because you have nothing to do’, because computers were flying the plane.

“Well, no,” he insists. “The flight has to be managed. The role is much more of management now – getting the fuel right, for example – because economics drive the airline business these days. Fuel is a third of all costs, and crew costs are quite close to that, which is why airlines are interested in reducing the crew. But skill and experience are still paramount so it is difficult to see how future one-man skippers would reach the necessary level. In bad weather and emergency situations the workload increases exponentially.”

Innes’s illustrious career ended with him being the highly experienced trainer on such charter airlines as Canada 3000 and Air 2000. His last post was flying long-range Boeing 767s for the Italian airline, Alitalia. He retired in July 1996; his logbook recorded over 17,000 hours, plus, of course, hundreds of hours in simulators.

“I had the best seat in the house,” he says of the stunning views he was privileged to witness all over the world. He took pride in getting his passengers safely to their destinations despite all the challenges that came his way.

“I was very lucky. I was paid all my life to do what was essentially my hobby. I enjoyed the work.

“There are many disadvantages to the job, as I point out towards the end of the book. But it is one of the very few careers where you could start a project and complete it the same day.”

Flight from the Croft, Whittles Publishing, £18.99.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here