MOST days I get the train to Glasgow. To do so I get in my 21st-century car to drive along 20th-century roads, cross an 18th-century canal and pass 1960s tower blocks and PFI-financed new schools to reach a railway line built in the 19th century. We are all time travellers, when it comes down to it.

Turning right at the Forth and Clyde Canal, the road squeezes between a stretch of grass and a bank of earth before it reaches Falkirk High School. It’s the kind of break in the urban landscape you hardly register as you pass. A flash of green and it’s gone. Most days, my head too full of the day’s business, it doesn’t even register. But now and again I look up and see the corner of Blinkbonny Road and imagine a Roman soldier standing shivering in the rain.

Completed in 139 AD, the Antonine Wall stretched for some 38 miles across the neck of central Scotland, from Bo’ness in the east to Old Kirkpatrick on the River Clyde. Over the last two millennia parts of it have been dug up, built on and covered over. In Falkirk itself it appears and disappears, history as jack-in-the-box.

On the corner of Blinkbonny Road there is a sectioned slice of it. The once massive Earth works are a mere dip here, a desire line tramped by thousands of kids at the start and end of the school day. It’s a mere whisper in the landscape.

Flow Country: Caithness bog could be on a par with Pyramids

And yet the wall, partial as it now may be, is the dotted line that helps write Scotland into history. Not quite an origin story; there were people living here for thousands of years before the Romans arrived of course. The wall itself was built nearly 20 years after Hadrian’s Wall, some 100 miles south.

But in tandem the two walls perhaps represent the moment when an idea of Scotland itself swimmily begins to coalesce, as told by the words of Roman authors and the things those Romans left behind.

Perhaps that’s why we remain fascinated by these invaders. This weekend in Falkirk a new exhibition opens in Callendar House. It's an invasion itself, from Roman England, a collection of skeletons of men who may or may not have been gladiators, discovered in York. In that sense it’s an exhibition about the otherness of Rome, the strangeness of it, the savagery. Down the road in Haddington an exhibition of the treasures of the Traprain hoard is currently on display. Another chance to measure the distance from then to now.

However far we might have come, though, we can’t escape. Historically, all roads lead to Rome.

In William Hole’s 19th-century frieze of Scottish historical figures that runs around the entrance hall of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, the earliest figures are all Romans. Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, the emperor who ordered the building of the Antonine Wall, Agricola, the governor in charge when the Roman army won a huge victory over the local tribes in Aberdeenshire in 83 AD, and the Roman historian Tacitus, who wrote an account of that conflict, along with Septimius Severus, who launched a brutal, doomed Roman invasion of Caledonia in the early third century.

The great and powerful, in other words. But who was that shivering soldier on the Antonine Wall, looking north towards the Forth and the Ochils, watching out for painted locals sneaking up with a spear? Why did he come here? What was Roman Scotland like? What did they bring and what did they take? What was their legacy? In other words, to paraphrase Monty Python, what did they ever do for us? And who was “us” anyway?

Read More: Walking the Antonine Wall

In the National Museum of Scotland, Dr Fraser Hunter, curator of the Iron Age and Roman collections, is standing in front of a first-century Roman marble head that was found in Hawkshaw in the Borders. Who this man, with his bowl cut hair and rather sour features, is we don’t know. But we do know he was Roman, Hunter says. And that makes him stand out.

“He’s probably a governor of Britain, most likely,” Hunter suggests. “He would have been a Roman citizen. He would have been raised in one of the big metropolises on the Med. He would have had his classic three Roman names.”

He is also, Hunter adds, one of the few actual Romans we know of in Scotland. The truth is the Romans on the edge of the Roman Empire were small in number. Legions came and went. The grunt work was done by non-Romans.

“Most of the folk doing the actual fighting are auxiliaries,” Hunter points out. “And auxiliaries are not Roman citizens. There’s a very clear separation between those who are ‘us’ and those who are not quite ‘us’. The legions, who are citizens, come in and do much of the initial fighting and they then mostly vanish further south.”

That means the soldier on both Hadrian’s Wall and the Antonine Wall would have been from France and Belgium, maybe eastern Europe. At Bar Hill, the highest fort on the Antonine Wall, looking out over the Kelvin Valley, there was even a unit of Hamian archers, originally from Syria.

It’s a measure of the multinational nature of the Roman empire, one that follows it right to the edge of that empire. All of this is spelt out in the things the Romans left behind. In the jewellery and ironwork and buildings and carvings and memorial stones and pottery.

On Bar Hill, the Syrians brought tagines from north Africa to cook in. In the National Museum huge amphorae can be seen that would have brought wine and fish oil, the essentials of Roman life, to the north of Britain. "Pottery is the tracer dye," Hunter points out.

READ MORE: 10 great places to enjoy Scotland's peerless wildlife

It’s also what marks them out from the people who lived here. "The Romans were very materialistic, Geoff Bailey, Heritage Engagement Officer for Falkirk Community, tells me a few days later. "Loads of pottery and bling."

I meet Bailey at Rough Castle. One of 17 forts along the Antonine Wall (turn right at the Falkirk Wheel), sited between Watling Lodge and Castlecary, it's the second smallest, an acre and a half in size, protected on one side by the Rowantree Burn. Now it's a palimpsest of what it was, a place to walk the dog and listen to the Edinburgh to Glasgow train whistle by.

Read More: Septimius Severus's war on Scotland

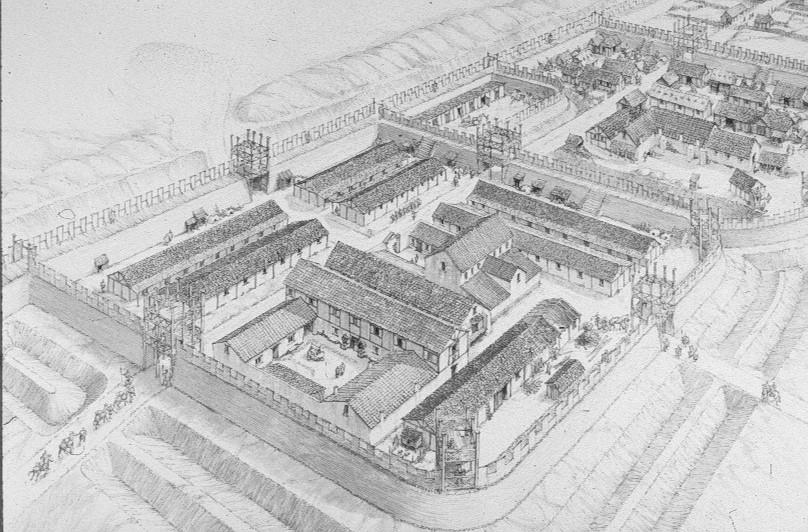

This morning, Bailey is conjuring up an image of what the fort once looked like for me. He points out where the commander's house would have been, the barracks and bath house. When it was built it would have been home to some 300 soldiers – Nervians mostly, from southern Belgium – who would look out across the Forth Valley towards the Ochils and down on a huge Roman fort in Camelon below and to the east.

This is frontier territory. In front of the fort there are the outlines of Lilia, two-metre-long pits that would have contained fire-hardened wooden spikes possibly smeared in rancid animal fat. "Even a scratch would prove fatal," says Bailey. "This is a minefield.”

Squint your eyes and you can maybe see Rough Castle as a Roman equivalent of a 7th Cavalry outpost. To the soldiers posted here, it was a foreign place, Bailey points out. "You are surrounded by people who speak a different language, have a completely different culture, who may or may not be friendly."

What does that make these soldiers? “The real aliens in Bonnybridge,” Bailey jokes.

Fraser Hunter suggests that local hostility wasn’t a given though. “When you look at the patterns of rebellion in Roman provinces, it’s the first generation. After a generation people get used to the idea. The real problems are those first 20 years.”

And the truth is a frontier culture grew up, one seen in the pottery and jewellery that has been left behind. “Some of these iron age sites are choosing to fight, some are choosing to deal,” argues Hunter. “And coming out of these sites you are seeing a rich range of Roman finds.”

Romans had military might, but they could also flex their soft power. Gifts can go a long way, Hunter suggests.

“Take a hoard like Lamberton Moor near the English border. Whoever buried this stuff had both Roman stuff – drinking vessels – and local drinking cups. They had locally made neck ornaments and Roman style brooches. So, they are really living in this in-between world. They’re neither Roman nor local.”

The empire, then, was never just a military expression. “There’s the honour and glory of conquering the country, of course,” says Hunter. “But there’s also the practical question of what can you extract? Metals is one thing. They may have been lead mining in southern Scotland. They may have been looking for things like gold, wild animals. We know that when the Colosseum is opened, among the games one of the victims is a Caledonian bear which has been captured on the northern frontier and been shipped to Rome and then slaughtered in front of the baying masses.

“And presumably slaves are one of the things they were looking for. That’s one of the hidden things in these economies. Warfare gives you slaves and for the Roman market that’s important.”

Inevitably, though, war was the first expression of empire. Both the Antonine Wall and Hadrian’s Wall are defensive fortifications but also a symbol of Roman strength. They speak of the power of the Roman empire. Rough Castle, Bailey points out, “would have said ‘resistance is futile. We’re here to stay.’”

But who was resisting? The problem with Roman Scotland is that only one side got to write the story.

In William Hole's frieze in the portrait gallery the first Scot to appear is the rebel leader of the Caledonians, Calgacus. Whether he even existed or not is debateable. But he was given life by Tacitus in the historian’s account of Agricola's invasion of Britain. On the eve of a huge battle at Mons Graupius in Aberdeenshire in 83 AD, Tacitus recounts Calgacus’s speech to his 30,000 men.

“Today will be the birth of liberty for Britain,” he said. “We will fight well because we are free. Here in the remote north, far away from the grasp of tyranny, have been born the best of men. The Romans are the pillagers of the world. Neither east nor west has sated them. To theft, murder and raping they give the false name of power. They make a desert and call it peace.”

It’s a remarkable speech, one that would not sound out of place coming out of the mouths of later Scottish leaders. But in the end, it’s Roman rhetoric, Tacitus putting words in Calgacus’s mouth, and aiming them at a Roman audience. Tacitus is talking to his own side, questioning the imperial project.

It should also be pointed out that Mons Graupius was a rout. The Romans put the Caledonians to the sword. Calgacus was the first Scottish leader who talked a good game, but couldn’t carry through.

That said, the story of Roman Scotland is the story of repeated invasions and retreats. Indeed, the Antonine Wall was abandoned just over 20 years after it was built.

Rome never conquered the whole of Scotland. Why not?

Fraser Hunter suggests there are two arguments, the nationalist and the internationalist. “So, the nationalist one is we were too tough, the landscape was too fierce, the climate was too horrible, the Romans just couldn’t cope.

“The other side is the internationalist one which is that Britain just wasn’t important enough, Scotland just wasn’t important enough.

“And people argue fiercely over one or the other, and the truth is probably as ever somewhere in between.

“Clearly, it’s a difficult frontier. But it’s also clear that if you’re given a choice between a rebellion in Britain and a rebellion on the Danube, the one you deal with is the Danube because it’s so much closer to Rome.

“So, for example, the very first invasion of Roman Scotland under Agricola, they sweep north, there’s the great battle of Mons Graupius which the Romans win. They’re poised to take over the rest of Scotland. And then a legion is pulled out because there is serious trouble on the Danube. The Danube is three days’ march to Italy whereas you have to march a long way from the Antonine Wall to get anywhere near Rome.”

All empires fall in the end. In 410 AD the emperor Honorius told the cities of Britain to look to their own defences. The Dark Ages (and there’s a telling appellation for you) had begun.

Some 2000 years later. Rough Castle is just an outline in the grass. The Roman fort in Camelon has long been built over. To find it now you would have to dig up Falkirk golf course, a railway line, a Tesco store and Alexanders the bus builders.

And yet, the mark of Rome is still on us. It always has been. In the years after the Romans left the Antonine Wall was used as a road, suggests Geoff Bailey. A line of connection rather than division.

Settlements grew up along and on the wall. There's a 12th-century motte-and-bailey castle at Watling Lodge. The wall continued to shape the geography of our lives.

Flow Country: Caithness bog could be on a par with Pyramids

But more than that the Romans shaped how we think of ourselves. There’s a theory, Fraser Hunter suggests, that the Picts only started calling themselves the Picts when they began to read about themselves and saw the name in Roman texts.

Our legal system, our language, our architecture, all of it drew on our classical heritage. “They may not have conquered the whole country but they changed everything that came afterwards,” Hunter says.

Somewhere inside there is a Roman in all of us.

Gladiators: A Cemetery of Secrets is at Callendar House, Falkirk until October 6. Treasures from the Hoard, an exhibition of Roman silver, uncovered at Traprain Law continues at the John Gray Centre, Haddington, until October 27.

GLADIATORS IN FALKIRK

Sarah Taylor on the story behind the "gladiators" in Callendar House

In 2004 archaeologists in York began excavate sites in Driffield Terrace in the city. The area is part of what is known to be a vast Roman cemetery, just outside the city walls. Some 80 bodies were discovered, dating back to the second century, many of them showing signs of violence. Nearly half had been decapitated around the time of death.

“There are multiple interpretations for this site and who the individuals buried there could have possibly been, including soldiers or criminals,” explains Sarah Taylor, exhibitions manager of the Jorvik Group. “However, the high proportion of young adult males and the frequency of evidence of violent trauma could also indicate that they were gladiators. The demographic profile most closely resembles a site at Ephesus in ancient Greece, which has been interpreted as a burial ground for gladiators. There have been no similar discoveries in Roman Britain.”

One of the skeletons has unhealed bite marks from a large carnivore bite. “Despite investigations, we still don't know exactly which animal caused this injury,” admits Taylor. “We can't know how this bite would have occurred, however one element of the gladiatorial games was the venatio, or staged animal hunt, when criminals were thrown to the beasts.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel