After decades of decline, indie bookstores are finally fighting back. As Independent Bookshop Week begins, Writer at Large Neil Mackay discovers that when it comes to success, personality goes a long way.

‘To whom it may concern, Sarah worked Saturdays at the bookshop for three years while she was at high school - when I say work I use the word in its loosest possible terms. She spent the entire day either standing outside the shop smoking and snarling at people trying to enter the building or watching repeats of Hollyoaks on 4OD. Although she was generally punctual she often arrived either drunk or severely hungover. She was usually rude and aggressive, she rarely did as she was told, and never in the entire three years of her time here did anything constructive without having to be told to do so. She invariably left a trail of rubbish behind her, usually consisting of Irn Bru bottles, crisp packets chocolate wrappers, and cigarette packets. She consistently stole lighters and matches from the business, and was offensive and frequently violent towards me. She was a valued member of staff and I have no hesitation in recommending her.’

When Sarah asked Shaun Bythell to write her a reference after a stint at his store The Bookshop in Wigtown, that’s the letter he handed her. Of course, this wasn’t a real life episode of Black Books - with a demented bookseller tormenting staff in between bottles of wine. Bythell didn’t actually send the same reference to her new employer - they got a much nicer one, saying what a lovely girl Sarah was, and such a hard worker.

That reference, though, is a measure of Bythell’s shop - witty, eccentric, slightly subversive and very clever. It also tells you something about the independent bookshop trade - that each store is an individual.

After years of decline, independent bookshops are finally bouncing back - seeing off the rise of the ebook, the predations of Amazon, the collapse of the high street, and the much exaggerated rumours of the death of the book. This weekend marks the beginning of Independent Bookshop Week - celebrating the success of the trade, and cheerleading for the public to keep the love affair burning.

It’s that sense of individuality which is credited with saving independent bookshops. The public wants something real, something which feels like - and here comes a much overused phrase - ‘an authentic experience’. People are returning to the physical world, finding the digital world lacking - and indy bookstores are the big beneficiaries.

READ MORE: The Golden Hare Books in Edinburgh wins bookshop of the year award

Alan Staton, director of strategy with the Booksellers Association, sums it up in one neat phrase: ‘We’ve reached peak Amazon.’ People are ‘celebrating the physicality’ of the bookshop and the book now, he says. And the secret ingredient ‘is about the experience of going to the bookshop’.

In a disconnected, rapid, and increasingly alienating world, bookshops are seen as ‘a safe place’, says Staton, ‘as an oasis’. And that sense of individual character - of honesty and realness - is the key to it all. "Every bookshop," says Staton, "reflects the personality of the bookshop owner."

THE OASIS

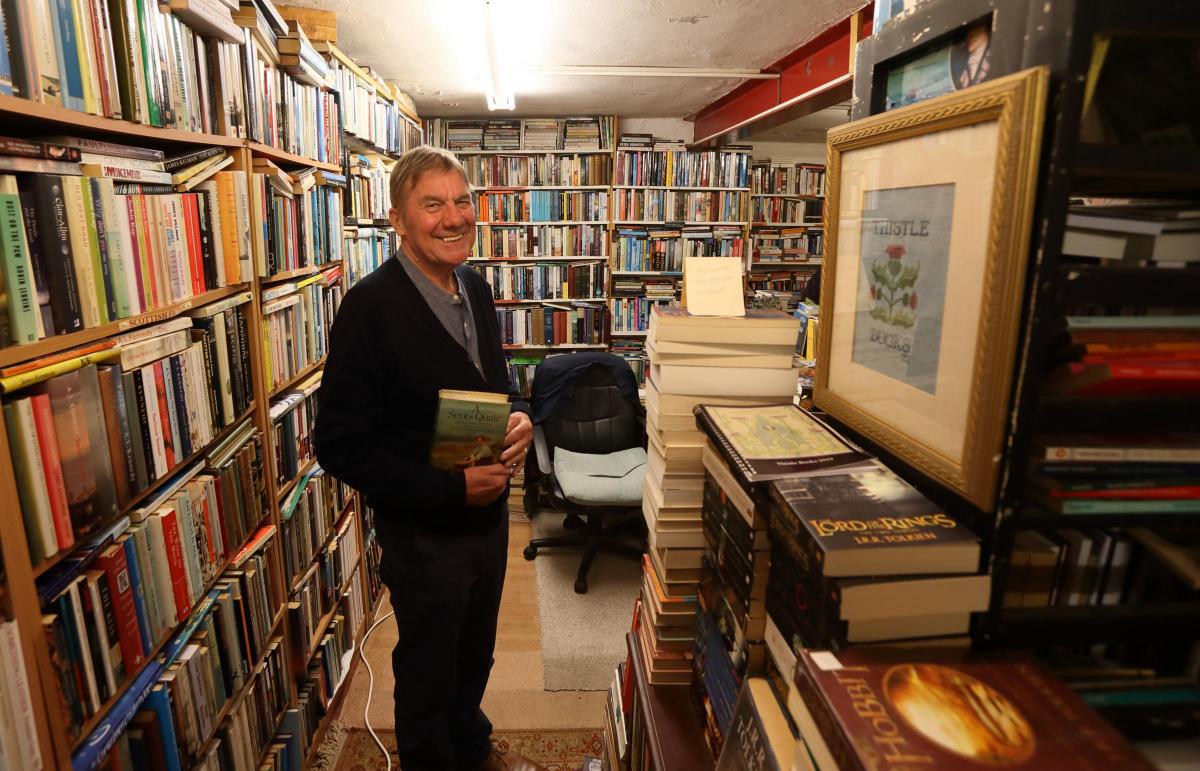

Hidden down a Glasgow lane not far from Great Western Road, there’s a hole in the wall store called Thistle Books. If a book lover had to build a sanctuary to escape the horrors of the modern world, this is it.

Robert Dibble sits at the back of his shop - thousands of books neatly ordered and curated on the shelves around him - looking every inch the retired history teacher that he once was. Bartok is playing on Radio Three.

There’s a spectrum of independent bookshops: the grungy secondhand joint that feels like a jumble sale, the tidy store that’s like a well-tended library, the edgy store selling radical political books, the antiquarian nook dealing in the weird and wonderful, all the way to the independent shop so slick and professional it’s hard to distinguish from the high street chain selling the latest bestsellers. Dibble falls into the well-tended library variety.

Twenty years ago, Dibble, now 74, gave up teaching and used his pay-off to buy Thistle Books. A lifelong collector, it was his dream come true.

A slow but steady stream of customers come through his doors - Dibble directing them with the precision of an sherpa to the location on the shelves of the secondhand books they want.

No-one is asking for the latest Stephen King. Sue is on holiday from Florida and she’s hunting for an obscure read. Jill from Fife wants a book on ‘the people who built bridges in the US’. Joe, who’s just graduated, buys Gore Vidal’s Lincoln, and begins extolling the greatness of the novel Fahrenheit 451 - which tells the story of a totalitarian society where books are burned.

Neil Mackay: How we can make tourism work in Scotland

One customer asks if there’s wifi in the shop, and a hint of a smile hovers around Dibble’s mouth when he says "sorry, no". The ills of the modern world are kept out.

"It’s certainly not a huge money-making venture," says Dibble, and it would be hard to make a living if he didn’t have his teacher’s pension. But then this is about his passion and his quality of life - he works four days a week, and there’s something lovely, he says, about sitting in his chair, reading, on a quiet day. Though in the winter, when the rain falls against the window, it can be lonely.

There’s a book for nearly everyone inside - though Dibble has his limits when it comes to quality control.

"I draw the line at Jeffrey Archer, both politically and for his literary skills,’"he says. This is a place where the rules of business are overthrown. The customer comes to him, Dibble says, it’s not him pursuing the customer.

Well known writers James Kelman and Bernard MacLaverty often pop in, browsing the shelves. "The beauty of independent bookshops is that there’s this air of serendipity," Dibble says. "You never know what you’re going to find." In the big high street chains, ‘it’s the same writers all the time, you aren’t going to come across some oddity, and that limits culture’.

Of course, the independent store can be a magnet for other oddities - obsessives will come in and bore Dibble with their pet manias; and he’s a captive audience for random evangelists.

Dibble can take it, though. He’s got a purpose after all - culture is at risk if books decline, and he’s there as one of the foot soldiers in the defence of reading. When he goes home after a long day at his store, he doesn’t switch on the TV, he picks up another book. "But lighter stuff than I’d be reading in the shop," he says. "Maybe a detective novel."

THE CAVE

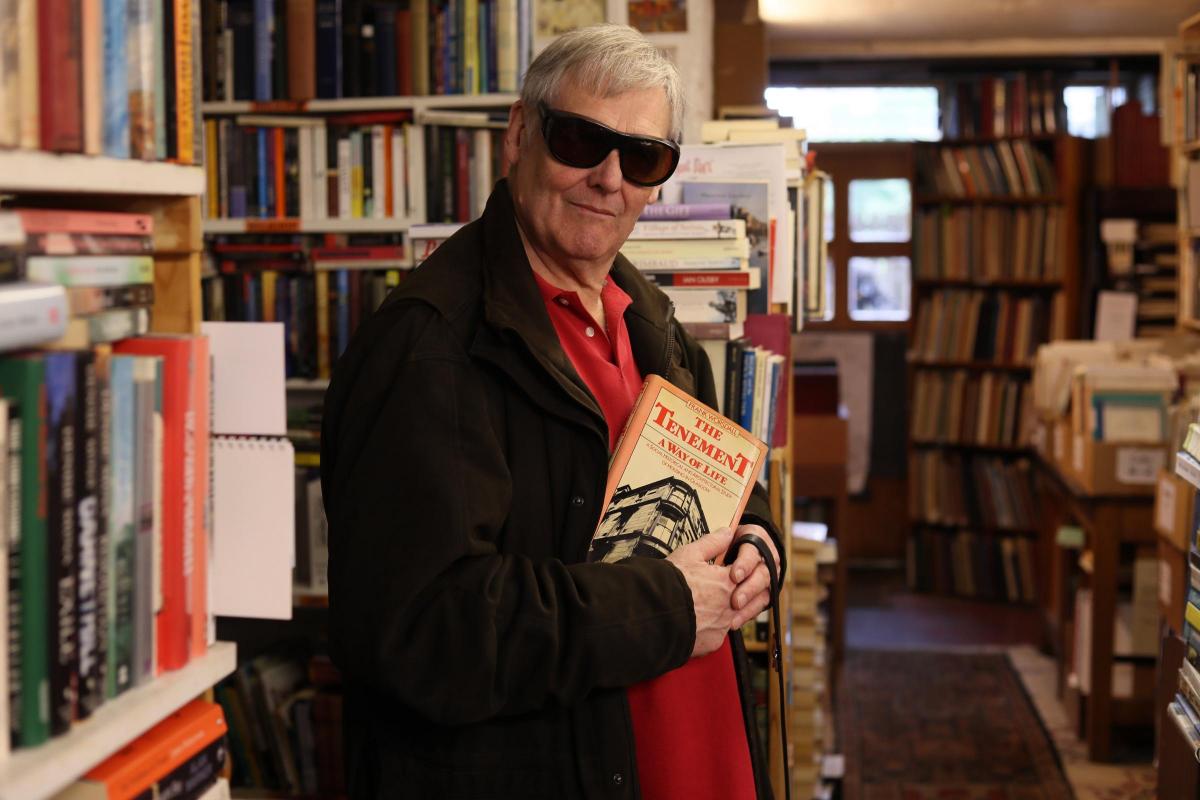

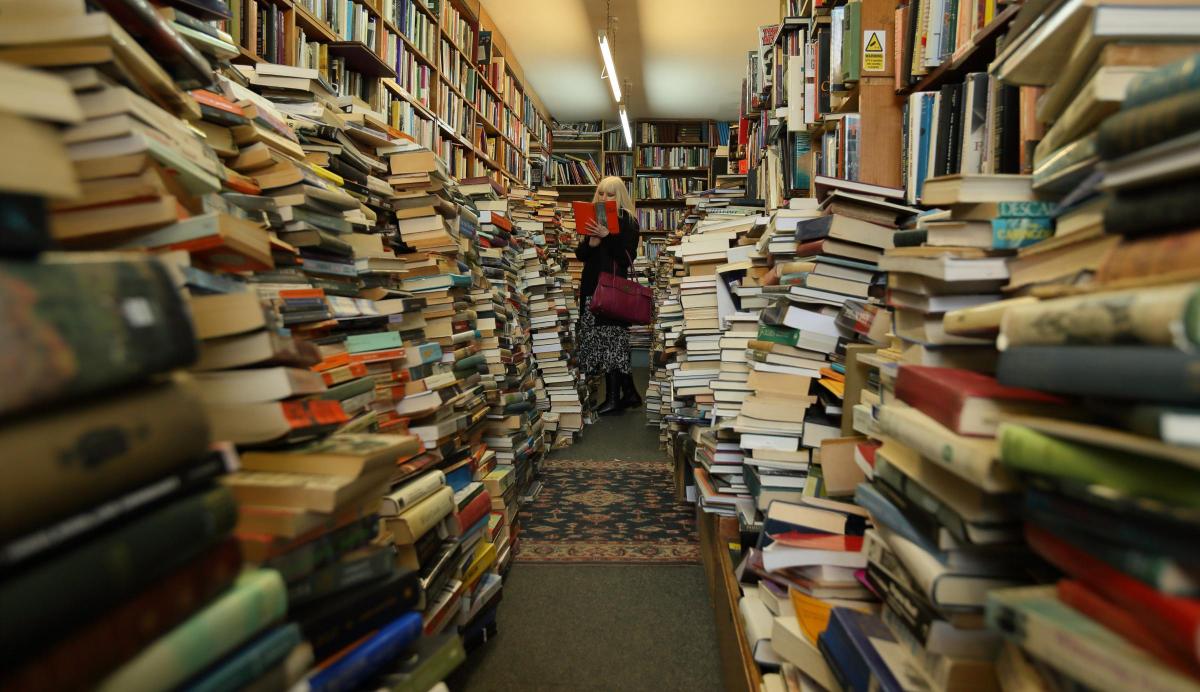

Voltaire and Rousseau. Two towering minds of the Enlightenment. Symbols of reason. You’d think, then, that a bookshop named after the pair would be a paragon of order and control. Wrong. Try chaos and confusion.

Voltaire and Rousseau is a jumble of a place. Books are piled on the floor, shoulder high, and four columns deep. There’s unreachable shelves, tottering towers, and it feels claustrophobic. Eddie McGonigle, who runs the store, says he knows where to find any book - but that can’t be possible.

McGonigle seems shy, unsure of himself. There’s not a lot of eye contact. His voice is so quiet it’s hard to hear sometimes.

Voltaire and Rousseau, in Glasgow’s west end, has been running for over 40 years. There’s an air of sadness, though, and the sense that perhaps this store, unlike so many bookshops now thriving again, might not last long. It’s struggling. McGonigle says he’s ‘doubtful it will last for the next five years … it might just die completely’.

Death plays a central part in the shop’s life - most of the stock comes from house clearances, family members selling their loved one’s books after they’ve passed away. Ebay has stepped in though - with relatives finding it easier to sell online than call in folk like McGonigle.

The customer base is dying too. "A lot of people who used to buy - they’ve passed away," McGonigle says. "There was a guy who used to come in every day and he would give us regular £40 a day, that was his whole life - just going to the bookshop - but you don’t see him anymore."

McGonigle is like a man out of time - genuinely mystified by the modern world. But he can always retreat into books. "If you’ve read HG Wells," he says, "it kind of transports you to a completely different world…"And then his voice trails off and there’s silence.

There’s a strange, and at times melancholy, sense of community. McGonigle, who’s unmarried and has no children, says Voltaire and Rousseau has a lot of regulars. "Some of it’s social, some people come and they say they wouldn’t know how to survive if the place wasn’t there, they come for their social chitchat. On a Friday, one guy comes to see the cats, then another guy will come in and he says he has to get out of the house, he has cabin fever and says he’d miss this place if it wasn’t there.

"One guy said that he believes it’s a national health service, the shop. He says it keeps him sane getting his books and having something to read. It’s the equivalent of getting tablets, he said."

I ask him if he has any happy anecdotes over the decades. "Um, yeah," McGonigle says, and he’s silent for a count of 10. "There was a guy who came in and said ‘I came in here 22 years ago and you were sitting in that same chair’, and then he said, ‘You are still there today’."

THE HIGH END

MARIE Moser is the darling of Scottish independent bookshops. Her store The Edinburgh Bookshop is as slick as any high street chain - but it comes with the personal touch that lies at the heart of the independent stores’ success story, albeit a highly polished and very professional personal touch. This is a well-crafted and well thought out ‘authentic experience’.

Eight years ago, Moser was tired of her marketing career and bought the Bruntsfield store, with Marchmont, Merchiston and Morningside as her customer base. She was a book obsessive as a child - reading dictionaries if there was nothing else to distract her.

She doesn’t touch the second hand trade - and is best known for children’s books. The store is light and airy, friendly and relaxed. But it all comes with thorough business acumen. Moser talks of the intricacies of retailing, of her audience, of the crisis on the high street, of following the customer’s needs. "This isn’t about just the bookshop I want to be in," she says. "It’s about ‘am I giving people what they want from us’."

But The Edinburgh Bookshop isn’t corporate, for all its slickness. The staff here know the books on the shelves as if they were their own children. Give them a few examples of what you last read, and what you fancy reading now - and they’ll have a clutch of recommendations for you in moments. Cat is an expert in children’s books, and what Joe doesn’t know about SciFi you could fit in a matchbox.

What places like The Edinburgh Bookshop do is ‘discover’ books that the high street then jumps on. Indies often give an author their first big break and the chains later make them superstars. "It’s a bit like BBC Radio 6 finding the next big thing in music," says Moser. "We can turn the volume up on things people weren’t expecting."

As she talks, her grumpy old Jack Russell called The Captain barks stubbornly. His mistress may be polished and slick, but The Captain keeps it real.

THE ACCIDENTAL HERO

Shaun Bythell says his life was going nowhere until he stumbled into bookselling aged 31. He’d studied law, and then drifted into a labouring job. At Christmas 2000, he went back to his parent’s farm in Dumfries and Galloway and paid a visit to The Bookshop in Wigtown, known as Scotland’s ‘National Book Town’.

The owner wanted to sell, Bythell wanted to buy but had no money. Miraculously, the bank gave him a loan and the rest is history. Bythell is now the the author of the acclaimed Diary of a Bookseller - a Polish film crew came to interview him on the same day we spoke - and his shop has 100,000 secondhand books over a mile of shelving. The store is a labyrinth of old typewriters, standard lamps, leather armchairs, and log fires. He wants his customers to enjoy a ‘salon-like experience’ when they visit. He doesn’t fail.

Bythell, funny and charming with that slightly posh Borders accent, knows he’s lucky. A chance meeting brought his love of books together with the perfect career opportunity. But it was a struggle. The 2008 crash crippled him - for years afterwards he noticed people paying in coins, not notes.

Bythell’s humour and charm are part of the reason he’s stayed afloat - people just like coming to his shop. He’s as candid in person, as he is in his comic memoir, and not afraid to gossip about himself, his staff or his customers.

Just this morning an elderly couple came into the store. "He said to his wife ‘what’s the name of that comedian I like?’. She replied, ‘I don’t know’, and he said, ‘oh come on, we’ve seen him loads of times’, and she said, ‘I still don’t know.’ Then he looked at me and said, ‘Anyway, have you got any books by him?’."

With the indie book trade now seemingly safe on its feet after years of hardship, Bythell’s good humour only deserts him when it comes to what the internet did to the industry. "Amazon is the most destructive thing that’s happened to the high street and bookshops in the last hundred years," he says.

Ironically, those years of hardship have left no real rivalry between independents - when the struggle for survival could have turned Darwinian. "We are all allies in the war against Amazon," he says.

INDIE BOOKSHOPS - FACTS AND FIGURES

AFTER more than 20 years of decline, the Booksellers Association is now reporting growth for the independent bookshop sector for the second year in a row.

The number of independent bookshops has grown to 883 stores across the UK, compared to 868 in 2017. Traders also reported increased sales and footfall over Christmas 2018.

However, 1995 still represents the high watermark for the industry with 1894 shops operating - but that was before advent of the internet.

Latest figures show that total book sales across the entire UK publishing industry were up 4% to £3.7bn. Physical book sales continue increasing, outpacing ebook sales which are in decline. Audiobook sales are rising.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel