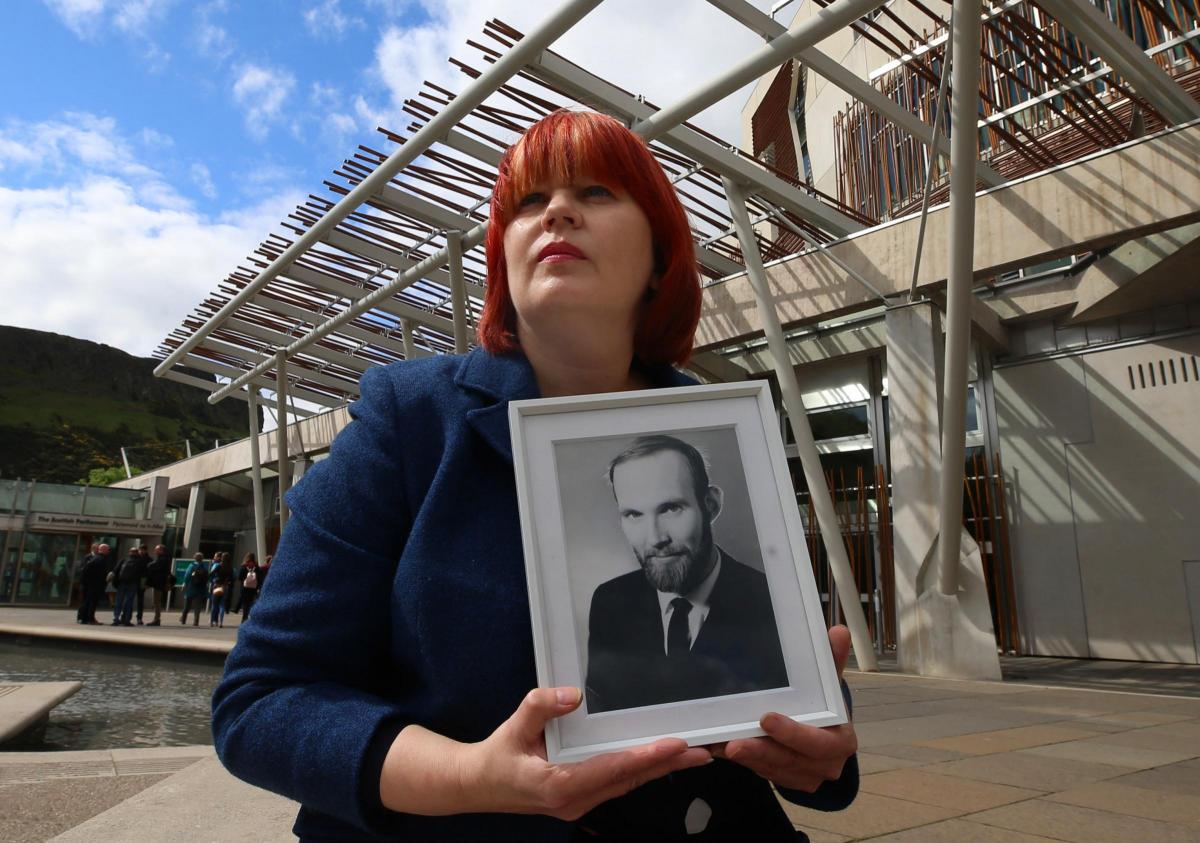

THE infection of up to 30,000 people with contaminated blood in the 70s and 80s has been called the biggest treatment disaster in NHS history. Thousands have died and more will die every day. A public inquiry is now under way and resumes in Scotland next month. Ron McKay meets one woman fighting for justice for her father.

WHEN she talks about her father’s long and tortured last days her voice begins to crack. It is only when she gets on to who she blames for killing him and failing her and her family that it regains a steely edge.

Justine Gordon-Smith holds the Scottish and UK Governments responsible. For their failure, not just to properly compensate for infecting their dad with the blood products which would finally kill him, but virtually abandoning him and his complex needs and leaving her and her sister to provide round-the-clock care as he became more and more ill.

Justine is one of four girls, two of her sisters live away, so it was left to her and her sister R (who doesn’t want to be identified) to look after their father Peter in Edinburgh as he deteriorated from a caring and funny man to a bedridden one they could barely recognise. All four were at his bedside when he died and she can be precise about it – it was 10.20pm on July 2018, just 20 days, she notes, after the Scottish National Blood Transfusion Service, which infected him, opened its “shiny new £30 million building in the Heriot Watt Centre”.

- READ MORE: Lawyers for Scots blood scandal victims want answers to why infected products used on NHS

Peter Gordon-Smith was a well-known figure on the Scottish music and entertainment scene, a musician and primarily double bass player – he backed Shirley Bassey and others – and he managed night clubs, worked at the Citizens’ Theatre in Glasgow under the legendary Iain Cuthbertson, even managed a youth hostel in the Edinburgh.

“He was a very outgoing man. He loved a yarn and a funny story. He could charm anyone,” she recalls. “He was a very talented musician and he was also very handsome.”

Peter was a haemophiliac. “When we were young I remember him having the odd bleed and he would go to hospital for a few days.” But it was manageable. “You were always very conscious of it and how an injury would affect him.”

It was in 1994 that Peter was told he was infected with the Hepatitis C virus, although he was not told how he got it or when. It is clear, however, from his medical records that he received clotting agents Factor VIII and cryoprecipitate produced by the transfusion service's Protein Fractionation Centre and administered by the Royal Infirmary in Edinburgh, the RIE.

“He was absolutely outraged when he was told. There was a distinct lack of information about how he became infected. Dad looked into suing the hospital, but that didn’t go ahead.”

Justine, like all the core participants in the new inquiry, has had to sign a non-disclosure agreement – in case information at this stage might prejudice future legal charges if anyone is held responsible – but she is determined not to be completely silenced.

- READ MORE: Tainted blood, the avoidable tragedy

For 10 years, from when he was told about the infection which would finally kill him, the family received no help or compensation. In 2004 the UK Government set up and funded three charities – while refusing to admit liability – one of which was the Skipton Fund.

“Around that time R found out about it in a newspaper article and we applied to Skipton.” Peter subsequently received £20,000 as well as £6000 a quarter. The money was used to do up his house, just a stone's throw from the Scottish Parliament.

Justine, a filmmaker, who was brought up in Edinburgh with sister R, had been living in London but in 2012 returned to pursue a doctorate at Edinburgh University in film and geography. She and R were shortly to become their dad’s full-time carers.

“He had been badly beaten in the 1989 and spent a long time in the RIE in 1990. He developed what they call an inhibitor - the clotting agents were facing increasing resistance - and he would turn over in bed and bleed, or opening the door, even shaking hands.”

In 2014 he developed sores in his legs which refused to heal. In that same year he had a fall in the bath, which led to him developing even more resistance to clotting. At the beginning of 2016 Justine asked the hospital to perform a liver test on Peter. It revealed cancer.

“We used to call him the Comeback Kid, he was so stoic, but this time he said ‘I’ve finally hit the buffers’,” she recalled.

Skipton awarded Peter a further £50,000.

In May 2017 he was told the cancer was terminal and there would be no further treatment. He was put on steroids and other drugs. “Up until he took the steroids he was a lovely dad. As soon as he took them he went.”

Justine and her R were now alternating carers. She says she was repeatedly told she was ineligible for carers allowance because she was a student and was unable to work. Later, the sisters were given 30 hours a week assistance.

Peter tried to kill himself in July, taking a massive overdose. After an alert, because the part-time carer couldn’t get in, Justine rushed to the house. Her father was saved.

“He was put on fentanyl [a powerful opioid]. This strange creature then appeared who was not our dad,” Justine recalls.

There was a second suicide attempt in September – “God knows how many Tramadol he took” – and again he was brought out of it.

“That was the only time I saw him as my dad again. He was so angry he wasn’t dead. He didn’t want to be alive.”

Justine and R installed a drug safe in the house so he couldn't try that method again, but he was later to attempt it a third time by stabbing himself. She adds, on the verge of tears again, “We had become his jailers and his prisoners.”

After the sisters had taken turns on seven-nights-a-week suicide watch without any support they were given a carer for three nights.

“Eventually we got seven nights a week, but only when Dad was so frail he required double staffing, but we got at least to sleep in our own beds,” Justine says.

In 2017 the Scottish Government set up the Scottish Infected Blood Support Scheme which replaced the Skipton and other charities. While it makes payments to those infected, and to partners and dependent children, non-dependent children, carers like Justine and R, don’t qualify.

“How can you say it’s generous? Why doesn’t the government just hold up its hand like the Republic of Ireland?”

The Irish Government has paid out over €2 billion in compensation, with the average award €432,935.

“My sister lost twenty-one thousand pounds from not working and I’m about seventy thousand out of pocket,” she says.

But it’s not about money, it’s about justice. “I am outraged at the way our father, our family and other victims and their families have been treated. I hear of cases on a daily basis that makes my soul weep. Families who have had to spend 30 years fighting for basic health care and benefits for children whose health and lives have been destroyed because of HIV or Hepatitis C infection from blood products.

“People are dying yesterday, today and tomorrow.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel