A Manhattan landmark is preparing to celebrate its heritage as a botanic garden with very Scottish roots, reports Sandra Dick.

The Rockefeller Centre graces the Manhattan skyline, one of New York City’s many landmarks and famous for its cluster of towering Art Deco buildings, the buzz of Radio City and twinkling Christmas ice rink.

Stretching to 22 acres and consisting of more than a dozen sky-high buildings, the urban expanse is home to art and culture, retail and restaurants, commerce and entertainment.

With its soaring stone buildings, bronze gilded Prometheus statue overlooking skaters on the ice and countless tourists, there is little elbow room for grass, trees and flowers to thrive unless on one of the many roof gardens.

Yet later this year the famous Rockefeller Centre will celebrate the legacy and life of a remarkable doctor and botanist, whose Scottish roots led to the creation of America’s first public botanic garden on its very site.

In August, the bustle of Midtown Manhattan will pause to reflect on a long-gone age when the streets, pavements and skyscrapers around them were a lush oasis of thousands of carefully cultivated native plants and meadows inspired by Scotland’s own Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh.

Recognition of the major role Elgin merchant’s son Dr David Hosack played in establishing the city’s remarkable early 19th-century botanic garden and a wealth of institutions which brought together its brilliant minds, has seen a stretch of formal gardens within the famous Rockefeller Centre planted in his honour.

The 845sqft Channel Gardens, a line of display gardens and water features in the centre of the 200ft plaza promenade, have been replanted with native plants, many no longer found growing naturally within the city, and the likes of which Hosack once featured in his sprawling Elgin Botanic Garden.

The Channel Gardens setting will also provide the backdrop to an event on August 31, when groups will gather to mark the 250th anniversary of Hosack’s birth.

The celebrations coincide with revived interest in the remarkable life of a figure who was celebrated by Americans in his lifetime but later faded into obscurity only to be revived partly thanks to blockbuster Broadway musical, Hamilton.

Hosack appears in the hit show in his real-life role of physician to both American founding father Alexander Hamilton and his foe, Aaron Burr, during their fateful duel.

But his transformation of what was once a rolling landscape of oak trees and wildflowers – and which by the 20th century would become a symbol of urban development and wealth – was rooted in his Scottish heritage.

Author Victoria Johnson, who explores Hosack’s life in her 2019 Pulitzer Prize-nominated book American Eden, said his passion was inspired by a trip to Edinburgh.

“When he finished his studies in New York and Philadelphia, he decided to go to the best medical education in the world which was at Edinburgh University’s medical faculty.

“His father was born in Elgin and had settled in New York. He was interested in seeing where his father had come from.”

Having arrived in Edinburgh, his eyes were opened by the breadth of knowledge of botany that thrived in the city.

Johnson adds: “He wrote ‘I am very much mortified by my ignorance of botany’. He was surrounded by people who were completely conversant in botanical science and he didn’t know a thing.”

Hosack resolved to improve his knowledge, and spent hours in botany classes and exploring Edinburgh’s gardens, including the original botanic garden in Edinburgh’s Leith Walk, which later evolved into today’s Royal Edinburgh Botanic Garden.

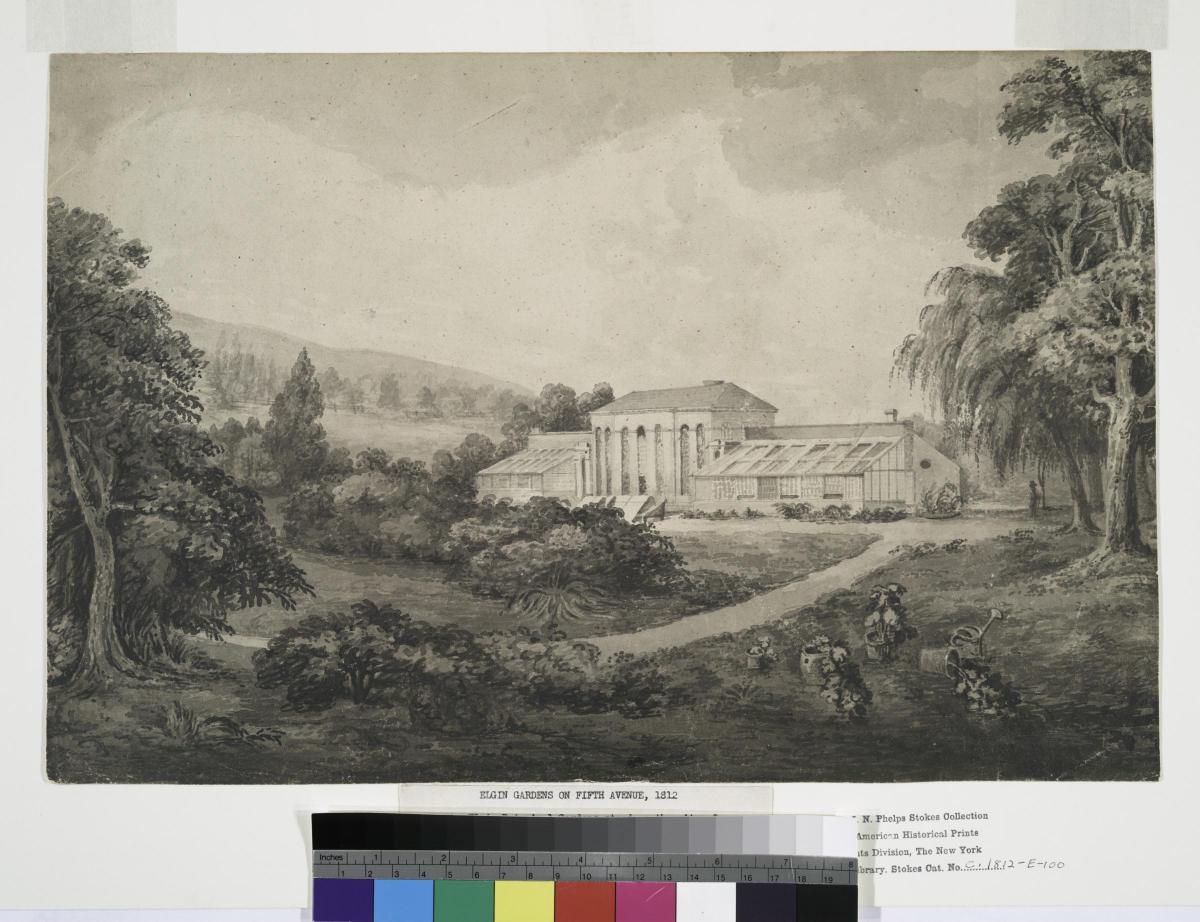

Back in New York, he ventured beyond the city limits to Manhattan’s untamed pastoral landscape where in 1801 he paid under $5,000 for a 20-acre stretch of land. There he built greenhouses inspired by the ones he’d seen in Edinburgh and paid tribute to his father’s birthplace by naming it Elgin Botanic Garden.

“He planted all kinds of agricultural crops,” adds Johnson. “It’s amazing to think he was growing barley, wheat, cotton and sunflowers on land where the Rockefeller Centre stands today.

“He experimented with native and non-native species. He taught students how to identify plants and prepare medicines, and they conducted chemical experiments to figure out whether plants that were not known could have medical properties.

“He built two 100ft conservatories which were clearly modelled on the ones he’d seen in Leith Walk and had plants brought from all over the world.”

The conservatories faced what is now Fifth Avenue, while streets which today are a hub for commerce and retail were surrounded by a belt of forest trees and shrubs. Exotic flowers, plants and fruits, which had never before been seen by New Yorkers, thrived within the garden walls.

His visit to Edinburgh and London had also inspired him to gather the city’s brightest minds to lay the foundations for organisations that moulded the city’s future.

“He saw his city through new eyes,” she says.

“It was a small town of 40,000 at the time, there were pigs walking through the streets and no major institutions.”

However, having spent over $1 million in today’s money funding his garden, Hosack’s wealth was running dry. It was first passed to the State of New York and then to Columbia College.

Hosack died in 1835, just a week after losing tens of thousands of pounds in the Great Fire of New York.

Meanwhile, his precious garden fell into ruin, the plants were ripped up, roads became overgrown and the glasshouses were destroyed.

Eventually, the college leased the land to John D Rockefeller Jnr to become the lavish Rockefeller Centre.

Johnson said the celebrations marking the anniversary of his birth brought his achievements full circle.

“He was an amazing man and I am delighted that the Rockefeller Centre is now celebrating the legacy of the land on which it sits.”

American Eden by Victoria Johnson is published by WW Norton

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here