THERE’S a quietly captivating moment, roughly three-quarters of the way through Malcolm Alexander’s book debut, that brings home the realities of life as a family doctor on the rugged and remote Orkney island of Eday.

Dr Alexander had arrived with his family some months earlier and had slowly eased into the rhythms of island life, and learning to appreciate just how central the church, the eight-pupil school and the GP’s surgery were to the inhabitants.

Now, here he is, relaxing as best he can from the stresses of being on call round the clock, allowing himself to be lulled by the wind and the waves.

He is pleased to glimpse oystercatchers; the plaintive sound of peewits reminds him irresistibly of his childhood in the Pentland Hills.

The water, he writes, is an acrylic mix of blues and greens. “The air,” he continues, “breathes in time with me as it ebbs and flows through the coarse heather stalks. This is close to where the heart gives out.” (That last phrase is indeed the book’s title).

But then a Loganair plane passes noisily overhead, and real life intrudes, as it must: on board are two policemen, come to investigate the disappearance of Ivan, a withdrawn local man who has done some work for Dr Alexander. Ivan is later found dead, from natural causes.

Dr Alexander had given up his Glasgow practice for various reasons and, together with his wife Maggie, a former anaesthetist, their four boys (Martin, Matthew, Michael and Murray) and their gaggle of pets (a rabbit, a guinea-pig, three geese, six ducks and a dog), had made the long journey to Eday, where he had been appointed as the local GP. The island lies off the Orkney mainland, watched over by Westray, Sanday, Stronsay and Rousay.

He wasn’t bowled over by the GP’s house and surgery when he first encountered them, however. The house was largely dilapidated, with a grubby bathroom; the surgery was equally desolate, with a torn examination couch and a computer and keyboard covered in dust.

It says much for him that he didn’t have an immediate change of heart and return to Glasgow and their “beautiful” west end home. But remain he did.

One of the very first patient files he opened was a poignant one: an elderly lady, Agnes – Nessie, who was born in 1919, and who lived almost her entire life on Eday, moving only briefly to mainland Orkney, after the Great War. Her medical history and, indeed, her life history were contained in that file.

Amidst descriptions of island life, and

of the islanders themselves, a key moment in the book occurs when Maggie, newly pregnant, has to be rushed to hospital in Aberdeen after serious complications arise, forcing Dr Alexander to look after their four sons while continuing to see to his many patients.

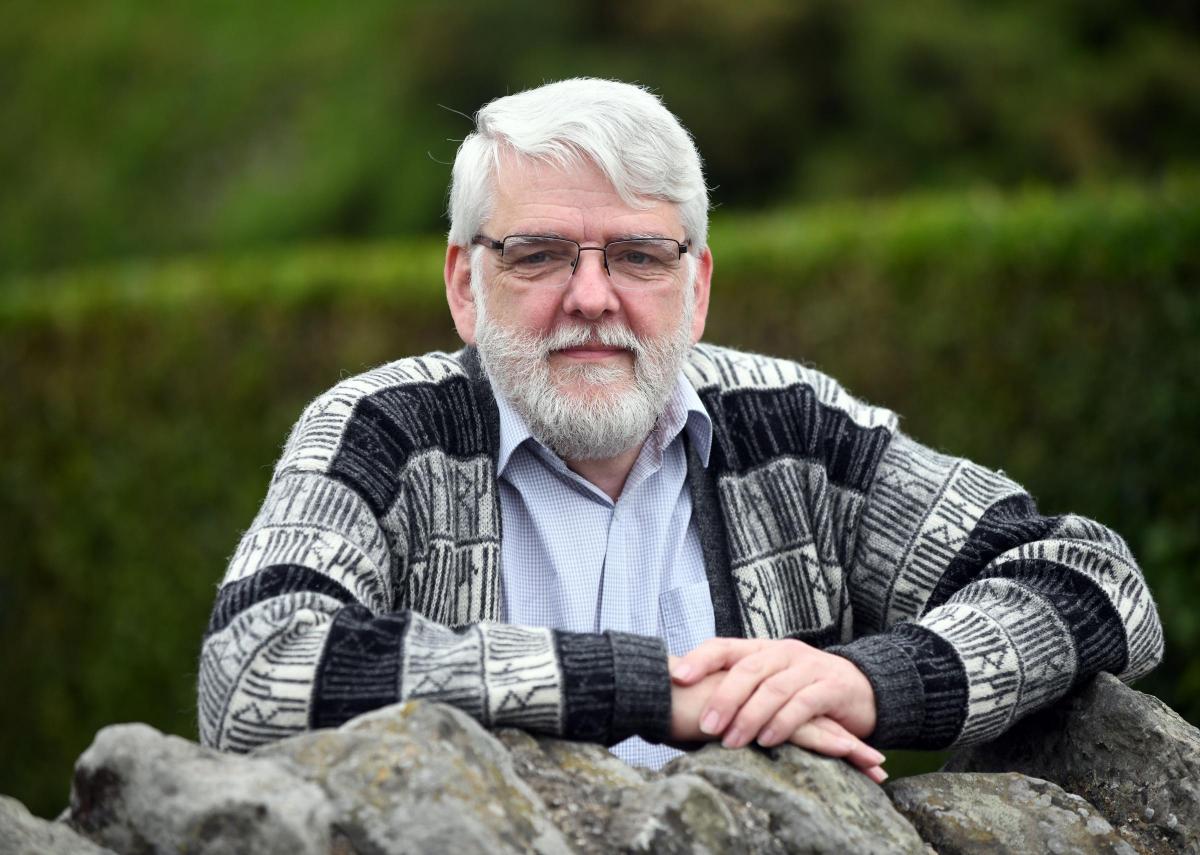

These and other events happened exactly 30 years ago. The good doctor retired in 2017 and now, aged 62, lives on another island, Bute. But in this 300-page book, which details his first year as Eday’s GP, they are as fresh as if they happened yesterday.

“I suppose it did surprise me, that I could remember so many details,” he says. “When I started out on the book, the heart of the story was Maggie having to go away. I’d been having an email exchange with my agent Laura [Macdougall, of United Agents], who had been looking for somebody who had done the kind of job that I had done. She asked me, what could I write?

“I thought the best place to start was the really emotional aspects, and then see if I can build from there. It was remarkable what I could remember once you put yourself back into the place.

“It was quite an emotional experience, a powerful one, to write about Eday after a gap of 30 years, to unwrap things you hadn’t thought of.

“One of the boys said it was fascinating to read about their life from somebody else’s perspective. They think, ‘oh, that’s how dad saw us at that time’, and it made me think about how I responded to them as kids.

“Obviously, in the book there are regrets and there are achievements, nice things as well, but it was quite testing at times, just to write some of the simplest things.”

Dr Alexander and his family remained on Eday until 1993. They went to Stromness, where he served as one of the GPs, and eventually, on Kirkwall, he became the medical director at Orkney Health Board; after that, he was Associate Medical Director at NHS 24 before going full circle and working at his local GP practice on Bute.

His book certainly has a strong sense of place. “That’s what struck me most particularly about the physical location, because you can just see so many things on it. One thing I didn’t mention in the book was the Stone of Setter, which is right in the middle of Eday and is one of the tallest standing stones in Orkney. These things are all over the place. You can’t escape the fact that there was a Neolithic presence. You can’t escape the geology, because it keeps erupting in front of you. It really is quite a remarkable place.

“I’ve gone back regularly to Orkney, managing almost annually, but have only once been back to Eday since we left. When Maggie and I last went, we had a look-round and tried to find folks, and chat to them. That was probably the hardest part, not being able to find them, because obviously a lot of them have died, or moved off the island.

“We subsequently tracked down a couple of people, though. Some of the kids are still there: we were able to meet the ones who had been at school with our kids, but most of the folk who created that environment, which almost had a 1950s feel to it, most of them have moved on.”

Had Eday changed much from the time when he was the sole local GP? “Physically, it doesn’t look as though it has changed much,” he says. “Maybe there’s a little less obvious crofting, with its stacks, its stacks of hay and barley and peat ... that seemed to have disappeared a bit, from what I could see.”

Can he envisage having been Eday’s GP for the last 30 years? “The challenge,” he says, “would have been keeping up to date. That would have been the real issue, Whereas now, [no GP] really stays in the one place exclusively, so they can get as wide a training as possible.”

For a first-time writer, he has done an excellent job with his account. In reference to that passage where he is enjoying nature just before he sees the Loganair plane coming in to land, he says: “I wanted to try to capture the feel of the peace, if you like, of the place, but also the speed which with reality can intrude.

“You had to get used to that. If you couldn’t live with that, then you had to move on, you had to go back to at least a town environment, where somebody else could take over and be on call.

“I loved it, but I was brought up with it – we were used to being on our own; we were used to seeing the road blocked with snow, and not fussing.”

Close to Where the Heart Gives Out: A Year in the Life of an Orkney Doctor ; hardback (£16.99), Michael O’Mara Books.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here