IT IS the most high-profile names and events that have lingered long in history of the suffragette movement; from the leadership of the Pankhurst sisters – Emmeline and her daughters Christabel and Sylvia – to the women who went on hunger strike and then suffered the brutality of force feeding, to the shocking death of Emily Davison when she was knocked down by the king’s horse at Epsom Derby.

However, women across Britain were involved in these kind of activities – including in Scotland, where militancy resulted in attacks on the city’s landmarks and buildings, a meeting which ended in a riot and even an attempt to cut off the city’s water supply.

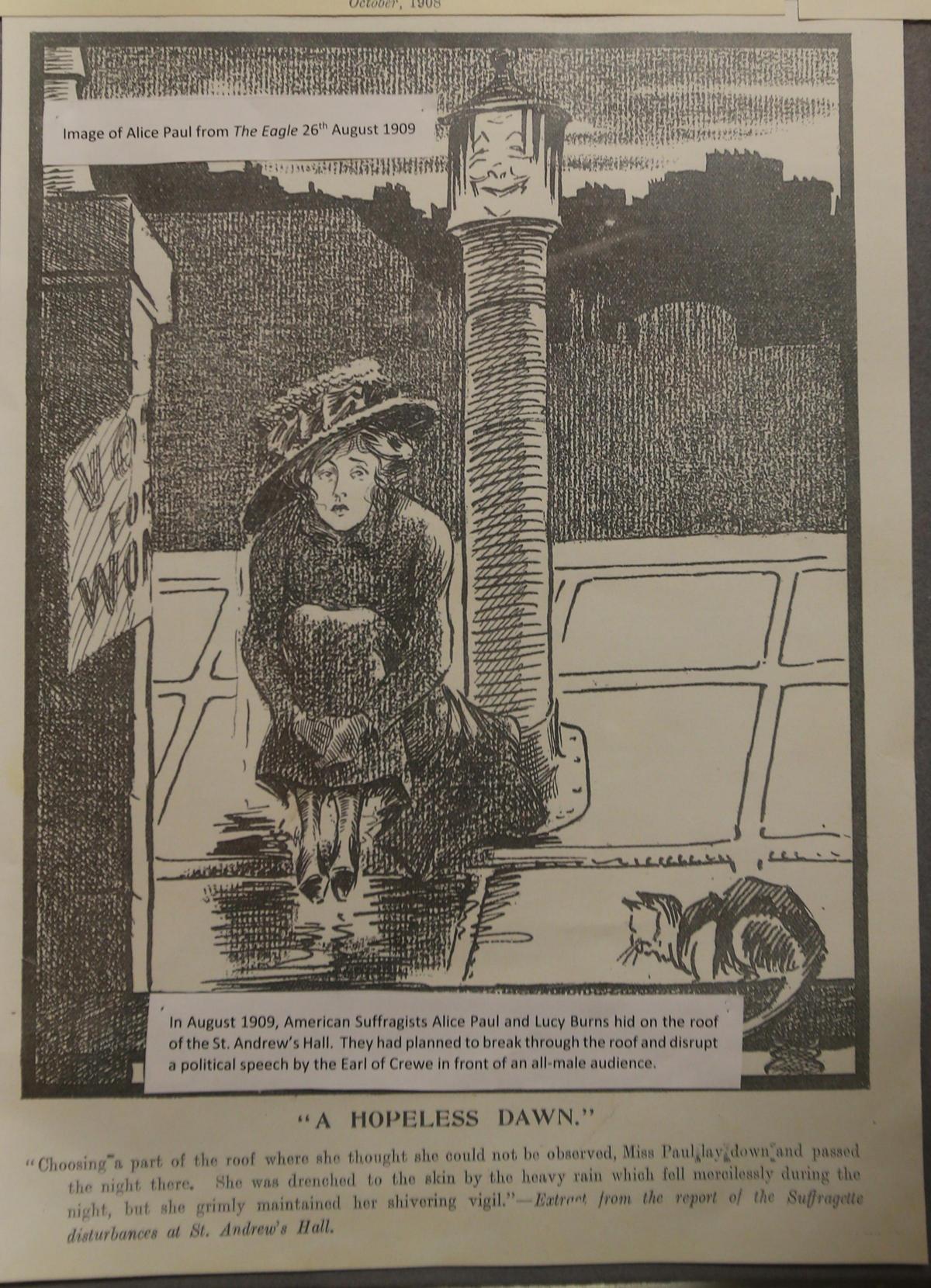

In 1909, for example, plans were hatched to stage a protest on the roof of the old St Andrew’s Halls, which had a renowned ballroom and was once a hive of meetings and concerts in the west end. The daring plot of the suffragettes was to disrupt a political speech by the Liberal politician Robert Crewe-Milnes, the Earl of Crewe, in support of the Budget.

But it was thwarted when some alert workmen noticed two planks of wood which they believed had been used to break into the halls. A search of the building was subsequently undertaken, where a young woman was found sitting near one of the ventilation shafts in the large hall: ‘She was in a woefully chilled and drenched condition, and it was quite evident that the lady had occupied her lofty position during the rainstorm which prevailed in the early hours of the morning. On being questioned, she stated that she had got on to the roof of the halls about one o’clock in the morning, with the intention of remaining there until the Earl of Crewe addressed the meeting in the evening, when she hoped to be able to bring the claims of the women to the franchise under his Lordship’s notice.’

The woman in question was Alice Paul, an American suffragist, who the report went on to say was allowed to leave the building and advised to ‘change into dry clothing, and partake of a warm breakfast’.

Another suffragette involved in militant action was New Zealand-born Janet Arthur, also known as Fanny or Frances Parker, who became organiser of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WPSU) in the West of Scotland and was involved in activities in Glasgow and the surrounding areas.

A niece of Lord Kitchener, on one occasion she confronted Winston Churchill, who at that stage was a member of Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith’s cabinet, as he travelled by train between Stranraer and Glasgow on the way back from a visit to Ireland. Frances, along with fellow suffragette Ellison Gibson, took up seats in a compartment next to him and quietly waited for an opportunity to speak to him:

‘Mr Churchill came boldly along and glared at the two women while speaking to another woman belonging to his party, who had come in beside them. Miss Parker then asked if she might speak to him. ‘What on,’ he barked. ‘On Votes for Women. No, I have had enough of that,’ he replied. Asked what the Government was going to do for women, he said. ‘For this behaviour you will not get the vote now,’ and walked on.’

Later, the suffragettes also attempted to confront Churchill as he left his hotel in Glasgow. One WSPU member, Annie Rhoda Greig, was arrested after striking the window of his car with her muff – a popular hand-warmer fashion accessory of the time – and breaking it.

In Glasgow, incidents linked to suffragette action were taking place on a regular basis, including acid attacks on post boxes. For example, in February 1913 a brown paper parcel was discovered by a postal worker in a pillar box at Charing Cross Post Office in Woodside Crescent, Glasgow. It contained a piece of cloth saturated with acid.

‘The acid, which was of an inflammable nature, had burned through the paper, and damaged a number of letters.’ it was reported.

Another form of attack aimed at disrupting communications was wire-cutting, such as one incident in which around fifty telegraph and telephone wires were cut in Kilmarnock in the Dunlop and Fenwick areas: ‘Cards bearing the words ‘Votes for Women’ were found at the scene of the outrage.’

In January 1914, the iconic Kibble Palace in Glasgow’s Botanic Gardens became the target of a bomb attack. One explosion shattered a number of windows in the glass palace, which had opened in 1873 in Glasgow. It was reported as a ‘Bomb Outrage’ in various newspapers, including the Daily Record: ‘Evidence clearly indicates that this was the work of militant Suffragettes, whose plans had been well laid.’

The police surmised it was the work of women: ‘Pieces of cake and an empty champagne bottle were recovered from the shrubbery immediately adjoining the footprints leading to the Palace. The Gardens were closed to the public at five o’clock on Friday night, and it is surmised that the women hid themselves until after the closing hour, and then took refuge in one of the greenhouses. The footprints clearly indicate the high heels of ladies shoes.’

The activities of both the suffragette and peaceful suffragist organisations were suspended as Europe plunged into war in 1914. Many turned their attention instead to urging women to do their bit to support the country.

The variety of work can be seen in one account which details the tasks which had been carried out by the Glasgow Society for Women’s Suffrage since the war began. This included a setting up of an exchange for voluntary workers, which supplied volunteers in response to requests, such as for canteen workers in munitions factories in Glasgow. An appeal letter sent out from the exchange also resulted in more than 3,000 sandbags being sent for troops.

In Glasgow, James Dalrymple, the manager of the city’s trams, recruited so many of his staff for the war effort that few men were left to run the system. Glasgow became the first city in Britain to recruit women drivers and conductresses during the war, with the novelty of the situation making headlines, such as this report in the Yorkshire Evening Post in March 1915:

‘The routes were chosen as being particularly suitable for the employment of the ladies, who have been supplied with a blue uniform, composed of coat, skirt and a cap, with facings. The cap is shaped like that worn by yachtsmen, and gives the wearers a distinctive appearance. The women discharged the duties yesterday remarkably well, although, as a precautionary measure, an inspector travelled on each of the cars with them.’

In the end, over the course of the war, a total of 1,080 female conductresses and 25 female tram drivers were employed by the city.

A report in 1915 noted that while much had been written about women undertaking work on tramways, railways, factories and shops, there was little known about the female workers undertaking the ‘arduous work’ in munitions factories. The women were reported to be able to undertake practically every stage of the work, which included manufacturing 18lb high-explosive shells, and only some tasks which ‘might prove beyond the strength of women’ were undertaken by men.

In Glasgow, three factories were built at Mossend, Mile End and Cardonald to manufacture artillery guns and shells. Lizzie Robinson worked in Cardonald and was awarded the Medal of the Order of the British Empire for her devotion to her duties, working seven days a week over eighteen months without missing a shift.

However, such work wasn’t entirely without any problems, as a strike by 400 women employed by Messrs Beardmore at its factory in East Hope Street in 1917 showed. The issue was raised in the House of Commons where it was stated that the origin of the strike was the dismissal of four women who were accused of restricting output: ‘Three of the women have been in the employment of the firm for two years…they catch a 5.25 train every morning, and do not return home until 7.25 at night.’

From the horrors of war emerged a hope that women, in demonstrating their capacity to play a far more active role outside the home, would be allowed to play a fuller part in society. Prominent suffragist Millicent Garrett Fawcett, who became the leader of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, summed it up in a famous quote when she said: ‘The war revolutionised the industrial position of women. It found them serfs and left them free. It not only opened opportunities of employment in a number of skilled trades, but, more important even than this, it revolutionised men’s minds and their conception of the sort of work of which the ordinary everyday woman was capable.’

Struggle and Suffrage in Glasgow: Women’s Lives and the Fight for Equality by Judith Vallely is published by Pen & Sword Books

Five Glasgow women who changed our lives:

Janet Galloway

A key figure in the organisation and work of the Glasgow Association for the Higher Education of Women and Queen Margaret College, the first women’s college in Scotland. Her activities to further the cause of women’s education included travelling abroad to the great exhibition of 1893 in Chicago. She is commemorated in a memorial window in Glasgow’s Bute Hall along with Isabella Elder and Jessie Campbell, who were also pioneers of education for women in Glasgow.

Margaret Irwin

Born in 1858, her mission was to improve the conditions for women in the workforce. She carried out investigations into the employment of female workers in several industries, raising concerns about issues such as long hours of work, low wages and equal pay. In one report, for example, she described a mother-of-seven who was the main bread-winner for her family, working as a trouser-finisher. The entire household of 11 people, including two male lodgers, lived in just two rooms.

Rebecca Strong

A nurse who was at the forefront of pioneering changes in her profession, she went to Florence Nightingale’s training school in London and became matron of Glasgow Royal Infirmary in 1879. At a time when it was perfectly accepted that nurses would drink beer on duty, she controversially introduced a ‘no drinking’ rule and other ideas to improve the status of nursing, such as uniforms. She set up a training scheme which included studies in topics such as anatomy and hygiene – a model which was accepted all over the world and helped turn nursing into a respected profession.

Janie Allan

One of the founders of the Glasgow and West of Scotland Association for Women’s Suffrage, she appeared in court in 1913 for refusing to pay taxes, arguing - unsuccessfully - that because she did not have the right to vote and was not considered a ‘person’, then expecting her to pay taxes was a form of ‘tyranny’. She was part of a deputation which went to Buckingham Palace in 1914 to demand votes for women and protest against torture of hunger-strikers. They were greeted with a force of around 1,500 policeman, and when they tried to force the gates, women were knocked down by mounted officers and struck by truncheons.

Eunice Murray

She was the only woman in Scotland who stood in the first election in which some women could vote, which took place in December 1918. A leading figure in the Women’s Franchise League, she stood as an independent for Bridgeton, Glasgow. However she was not successful and had to forfeit the £150 deposit paid to stand for election. It would be another five years before a woman in Scotland became an MP, with the election of Katharine Stewart Murray, the Duchess of Atholl, in Perth and Kinross.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here