ELEVEN months ago, Glasgow University announced a "pro-active programme of reparative justice" after a year-long study found that it had derived "significant" financial support, donated from profits made in the slave trade in the 18th and 19th centuries.

The report said that though the university had played a key role in the movement to abolish slavery, it had also received gifts and bequests from people whose wealth – or at least part of it – stemmed from the slave trade.

The report estimated that the modern-day value of such donations could be in the order of tens of millions of pounds. The university said it intended creating a centre for the study of slavery, and a memorial or tribute at the university in the name of the enslaved. Yesterday it signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the University of the West Indies to enhance academic collaboration between them.

Another step is a new exhibition, Call and response: The University of Glasgow and Slavery, to be staged in the university chapel. It invites the public to react and respond to the histories of enslaved people and their role in the university’s story.

The exhibition features photographs and stories of a selection of objects to explore the "often unknown and unexpected ways" in which some items within the university’s collections are linked to the history of slavery and the abolitionist movement. A number of people connected to the university were asked to give their response to an object and its history.

Dr Christine Whyte, a historian and storyteller of the exhibition, helped to curate the exhibition with colleagues from the university library and The Hunterian.

Of her chosen item – The Memorial Chapel, which will be the exhibition venue until the end of the year – Dr Whyte, a lecturer in Global History, said: “For many centuries, people of African descent have called the attention of the world to the injustices of the slave trade, slavery and racism. The University of Glasgow is responding to that call, by opening this dialogue about reparative justice. I hope this exhibition can provide space for reflection on the memories of enslaved people, and serve as a testimony to the tireless activism of Scottish anti-racism campaigners.”

Slave Bible

GRAHAM Campbell, a Glasgow City Council councillor, an activist for African Caribbean issues in Scotland and external advisor to the historical slavery report. His object is a rare Slave Bible from 1807, intended for use by slaves in the British West-India Islands. It was published in London for Christian missionaries and was heavily edited to remove anything that might be seen to incite a rebellion. The bible was among 10,000 books donated to the university by insurance broker William Euing in 1874.

“Bob Marley once sang about mental slavery ‘none but ourselves can free our minds’. Pro-slavery ‘Christians’ were very deliberate in editing the Bible to exclude its most inconvenient truths about freedom, emancipation, liberty justice and mercy. Enslaved Africans and their descendants had these mental chains smelted from a peculiarly Scottish mixture of white-supremacist racial hatred and enlightenment rationalist missionary zeal. This bible was as effective a tool of enslavement as any cast-iron chains.”

Collections

PROFESSOR Heather Ferguson, infectious disease ecologist, University of Glasgow. Her object is a Citron Bug (Leptoglossus gonagra). It is part of the collection of the anatomist and physician Dr William Hunter, who bequeathed his collections to the university for research and teaching. It originated from Equinoctial Africa and was collected by Henry Smeathman (1742-1786), an English naturalist who was paid to travel to Sierra Leone to collect and send back specimens to Europe to enrich scientific understanding. He and his insects travelled back to Europe via the West Indies aboard a slave ship.

“In the 18th century, British entomologists carried out important research on the natural history of tropical insects. However, their methodologies were often exploitative, ignorant and inhumane. Today strict codes of ethics govern our work. Equitable partnerships with African scientists, communities and institutes are essential. It is not widely known that the founders of my discipline were involved in the slave trade in such a direct and disgraceful manner. This should be acknowledged and addressed as we seek to move forward.”

Foulis Academy

JULES Koch, Museums Studies postgraduate student, University of Glasgow. Her object is The Interior of the Academy of Fine Arts by David Allan (1744-1796).

This artwork depicts the Foulis Academy of the Fine Arts, established in 1754 within the university buildings on the High Street. Its founders were Andrew and Robert Foulis, who sought funding from the wealthy merchants of the city to start their school. Those merchants – Campbell, Glassford and Ingram – made their money from the slave trade in the West Indies.

“It is a privilege to study and work at an institution with such historic collections. Objects in museums have the ability to speak to, or share, ‘hidden histories’ from a multitude of perspectives. Understanding the back story to beautiful objects, like this image of the Academy of the Fine Arts, can be shocking and difficult. But it is fundamental to how we interpret and understand our connection to the past.”

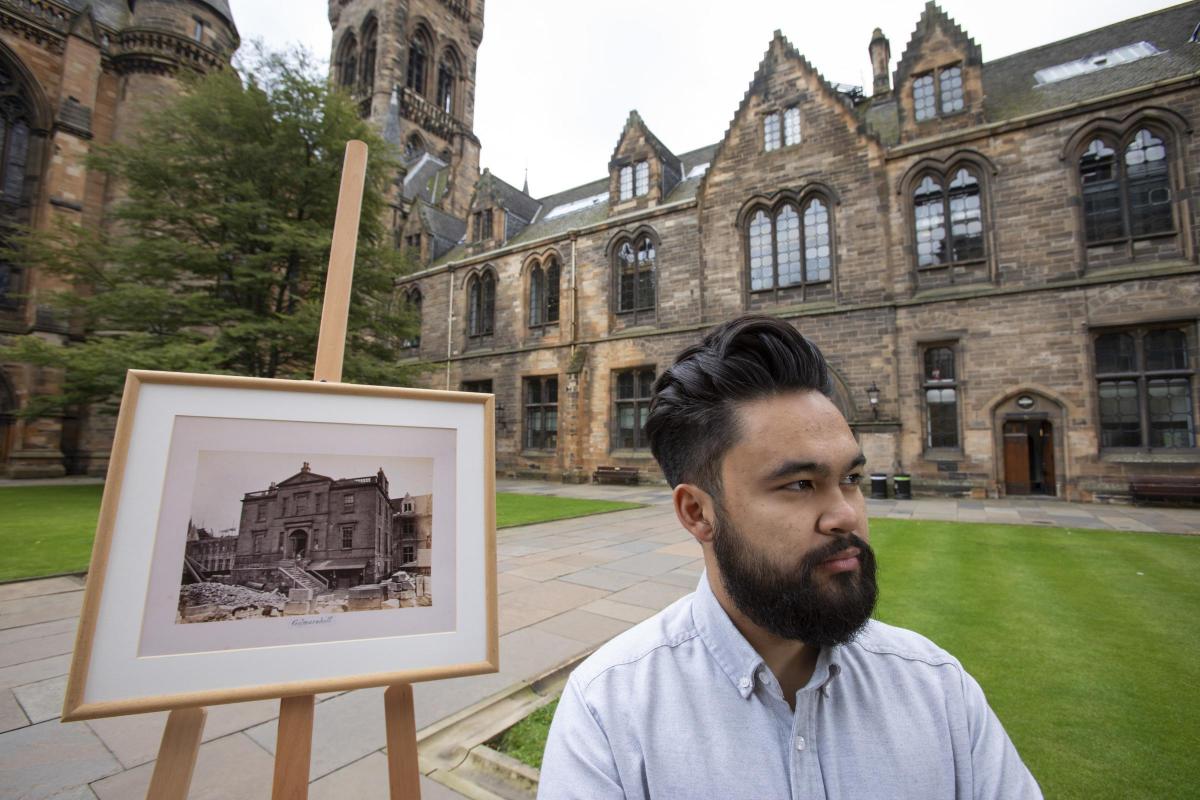

Gilemorehill House

SCOTT Kilby, president of the University of Glasgow Students’ Representative Council, who chose a photograph of Gilemorehill House, with the then-new Gilbert Scott Building of the University of Glasgow being built around it. From 1802 to 1845, Gilmorehill House was the family home of prominent West India merchants who traded in tobacco from plantations in the West Indies and the United States. Enslaved people were forced to work on those plantations. They themselves had been traded in West Africa for Scottish products such as cloth.

“This is a deep reminder that we shouldn’t shy away from the past and face up to the flaws in our history. Initially upon looking at this, it’s striking that this building was architecturally incredibly beautiful, but that thought is quickly followed by a profound sense of remorse knowing that I walk over the foundations of this building on a daily basis, knowing what it represents, what it embodies.”

The Jamaica

PROFESSOR Sir Geoff Palmer, Jamaican Honorary Consul to Scotland and an external advisors to the historical slavery report. His object is a drawing of The Jamaica, a 146-foot-long, three-masted iron sailing vessel, built on the Clyde in 1854 by William Simons & Co. In the 1860s, the company constructed blockade-running vessels to help wealthy Glasgow merchants evade the economic consequences of the American Civil War. The Jamaica was built for Stirling, Gordon & Co, West India Merchants, whose partners owned plantations in Jamaica. The family of one of the partners donated £3,000 towards the construction of the University buildings on Gilmorehill in the 1860s.

“This 1854 design of a Glasgow-built sailing vessel, named Jamaica, reminded me of Jamaica’s long historical links with Glasgow. Jamaica Street was opened in 1763 for trading in goods produced by chattel slaves in the West Indies. The Stirling and Dennistoun families made large fortunes from this cruel slavery. Although the history of this slavery cannot be changed, exhibitions such as this can enlighten and change the consequences.”

Full details can be found at https://www.gla.ac.uk/schools/humanities/slavery/

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel