50 Victoria Drummond:

First female marine engineer and war hero

If Victoria Drummond’s life speaks of anything it’s fierce and dogged determination. The first female marine engineer in the UK, she forged a gender-role-bending path. Only after persistently sitting the exam 37 times – and being rejected many of those times because she was a woman – did she become a chief engineer. Born at Megginch Castle, Perthshire, the god-daughter of Queen Victoria, she was from an early age interested in mechanics. Inspired by the machinery in the Robert Morton and Sons engineering works near her home, in 1915, at the age of 21, she did an apprenticeship at the Northern Garage Perth. This would be followed by another apprenticeship at the Caledon Shipbuilding and Engineering Company, Dundee. During the Second World War, she served on the SS Bonita, which was attacked by enemy aircraft and was commended for her bravery and leadership.

49 John Knox:

Religious revolutionary

and educationalist

John Knox was a pillar of the reformation. It was said by one English ambassador that to hear him preach was like was “having 500 trumpets blowing in one’s ear”. The sound of those trumpets still reverberates. We live in a Scotland in which that Presbyterian sensibility lingers, in which we, in spite of religious diversity and the waning of the Church of Scotland, are frequently caricatured as a Calvinist nation. Knox, a former Roman Catholic priest from Haddington, went on to become a firebrand prophet, railing against idolatry. His journey towards bringing the Protestant revolution to Scotland involved a period as slave in the French king’s galleys and time in Geneva where he came under the instruction of John Calvin. His legacy, however, is more than the established Church of Scotland. It was an education system and the idea of universal schooling, as well as new ways of providing for the poor.

He was also, many believe, a key influence in the American revolution. A black mark lingers against him for his misogynist rantings – though it should be said that his belief in the inferiority of women was typical of his time, and his famous First Blast Of The Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment Of Women was directed not at all women, but specifically the Catholic queens.

48 John Loudon McAdam:

Road-making revolutionary

Born into an aristocratic family, John Loudon McAdam moved to New York in 1770, made his fortune there, and returned in 1783. Then he started to experiment with road construction, dabbling with using roadstones in the building of a road from the local highway to his newly acquired estate. He would go on to write papers on the “Scientific Repair and Preservation of Roads”.

In 1816, when he was appointed surveyor to the Bristol Turnpike Trust, he decided to remake the roads under his care with crushed compacted stone layers, shaped with a convex camber for drainage. It was the greatest revolution in road construction since Roman times. His roads were smoother, cheaper and longer-lasting.

By the end of the 19th century most roads in Europe underwent what became known as macadamisation. McAdam’s brilliant idea is still there, albeit with a few adaptations including a bit of tar, beneath our wheels whenever we travel.

47 Janet Keiller:

Marmalade matriarch

In the 18th century, Janet Keiller’s husband, John, bought a cargo from a Spanish ship after it sought refuge from a storm, for the cake and sweetie shop they ran in Dundee. It happened to be loaded with Seville oranges and Keiller made good out of a bad lot by boiling them with sugar and making marmalade. By 1797 the Keiller factory had begun manufacturing marmalade.

Food writer William Sitwell states: “Janet Keiller called her version Dundee Marmalade and it sold so well that it became a byword for Scotland, a key part of Scottish breakfast, a symbol of excellence, a matter of national pride.”

Did Keiller invent marmalade? The idea is much debated. The Spanish had been making something like it from quince for decades. One food historian created a stooshie in 2016 when he suggested marmalade had been featured in English recipe books long before Keiller’s creation – though he did confess she was the first to mass produce it.

But Three Chimneys chef Shirley Spear, creator of the hot marmalade pudding, retorted: “There are amazing recipes which go back hundreds of years. But I think marmalade as we know it today is more likely to have been of the kind that the Keillers made.”

46 Mary Somerville:

Self-taught polymath and world’s first scientist

Long before Brian Cox or Sir Patrick Moore, there was Mary Somerville, a great populariser of science in general, but also her most favoured field, astronomy. In 1834, she became the first person to be described in print as a “scientist” – since she was more than just a physicist or astronomer, but could not be called, the popular term of the time, a “man of science”.

Much of her thinking was ground-breaking. It was Somerville, for instance, who inspired the discovery of Neptune, when she theorised that the difficulties in calculating the position of Uranus suggested that there may be another planet out there.

Twenty years before Charles Darwin published The Origin Of Species, she was writing, in her book Physical Geography, of man being “a fellow-inhabitant of the globe with other created things, yet influencing them to a certain extent by his actions, and influenced in return”.

It’s not just that she was a brilliant self-taught mathematician and scientist, but that she had a gift for communicating ideas. Somerville herself once wrote, “I was intensely ambitious to excel in something, for I felt in my own breast that women were capable of taking a higher place in creation than that assigned to them in my early days.”

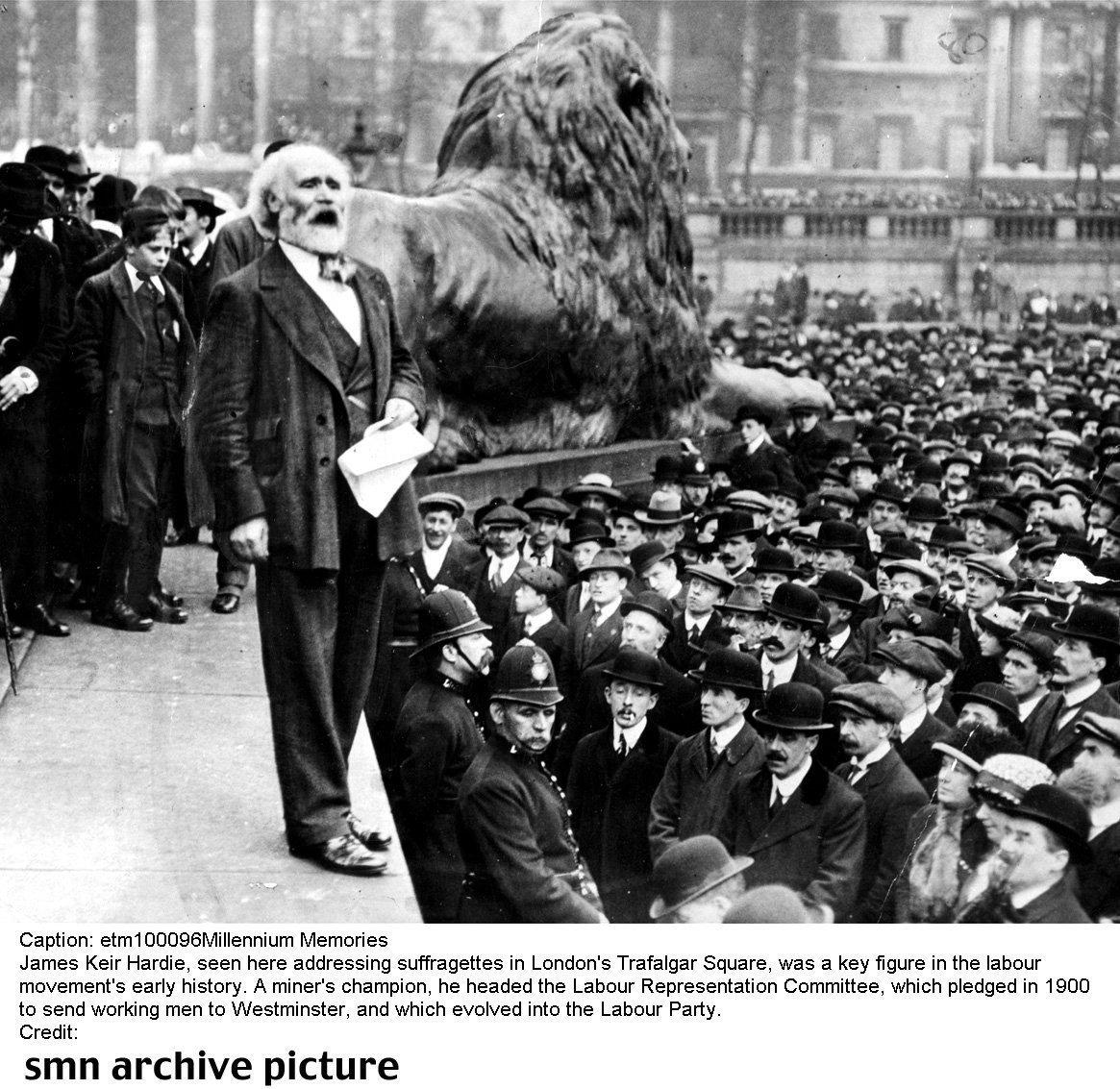

45 James Keir Hardie:

Founder of early Labour party

Labour prime minister Clement Atlee once said, “Hardie was not only born of the working class, he remained of the working class. Few members of parliament had a greater effect upon the House of Commons than Keir Hardie. Before the end of the 19th century parliament consumed itself very little with the life of the common people. The turning point came at the end of that century and Hardie symbolised that change.”

Politics would not be what it is today without the man once described as the “prophet and evangelist” of Labour, Britain’s first working class and socialist MP, as well as the first leader of the Labour party, he was born in a one-room cottage in Lanarkshire, to an unmarried mother who was a servant. He was reputedly illiterate to the age of 17, and was working in the mines by the age of 10.

The Scottish Labour Party, of which he was secretary, came into existence in 1888, and in 1893 he helped form the Independent Labour Party. What he demanded was a legal minimum working age, eight-hour day, and nationalisation of the mines. The House of Commons he entered was one which he found to be a “putrid mass of corruption”.

He also supported votes for women and opposed Britain’s entry into the First World War. As the late Bob Holman once put it, “He detested titles, pomp and expensive lifestyles. Few contemporary Labour MPs put principles before pocket. And that is why Keir Hardie is worth remembering.”

44 Sir Sean Connery:

Actor

Sean Connery has to be our greatest cinematic export. People magazine declared him “the Sexiest Man of the 20th Century”. In 2013 he topped an American poll for the greatest British actor of all time. No other Scot has gone on to become quite the international Hollywood icon that Connery did. None has made Scottishness seem quite so suave. He was also the James Bond that defined Bond.

It was Dana Broccoli, Albert “Cubby” Broccoli’s wife, who identified him as the man for the role – appreciating not just his physique, but the fact that he “moved like a panther”.

His Bond, the ladykiller, may seem like a dinosaur in the #MeToo era, but he still dazzles. Connery brought to Bond something meritocratic rather than aristocratic. He was a former milkman and bodybuilder, who grew up in a two-room Fountainbridge flat with an outside toilet. Connery might have worn a hairpiece in every Bond movie but he didn’t fade like many other matinee idols, as he greyed, but held the screen in maturity, clinching a supporting role Oscar in The Untouchables. In his biography, Being A Scot, the longtime backer of independence attributed his success to being Scottish.

43 Isobel Wylie Hutchison: Poet, author, botanist, explorer and painter

Isobel Wylie Hutchison walked across Iceland solo, when everyone was warning her not to. It has been said she was the first Scotswoman to travel in Greenland. In the 1930s she journeyed as a lone woman across the top of Alaska and found herself marooned for seven weeks on a sandspit with a fur trader – then wrote a compelling memoir about it. In terms of inspirational women who lived outside the expectations of her age, she was a trailblazer. Rather than marry, Wylie Hutchison, who was brought up in Carlowrie Castle, devoted her life to travel and collecting rare plant species. When St Andrews University awarded her an honorary degree in 1949, it was said that she displayed “that indomitable spirit which defies hazard, danger and discomfort, and is the source of all great human achievement”.

42 Mary Queen of Scots: Tragic queen and female leader

More than 400 years after her bloody execution, there’s still something about Mary. Recent years have seen it made “woke” in a film starring Saorsie Ronan, and charted by historian Kate Williams in Rival Queens, an examination of Mary’s relationship with England’s Elizabeth I. Williams’ book has been described as “the great rivalry reimagined for the #MeToo generation”. Why does she remain relevant?

In part, it’s that her story remains so compelling – its charged romance, the murder of her secretary and favourite David Rizzio, the killing of her husband Lord Darnley and her violent end. But also there’s a fascination with the relationship between the two queens. As Kate Williams puts it, “If we look at her in terms of queenship, she engaged in many acts that Elizabeth was congratulated for – but Mary did the same and lost everything.”

41 James Watt:

Inventor of steam engine and father of industrial revolution

It was an idea that popped into his mind while he was out for a Sabbath stroll. When James Watt perfected the steam engine in the late 18th century, he was putting into place the key element that set off industrialisation. So many things followed on, including locomotives, steam-powered ships, factories of multiple types, the transformation of the then water-based cotton industry, Britain’s evolution as the first industrial country.

It was a revolution that would ultimately lead to the biggest challenge we face today: climate change. Watt’s genius stroke was to separate the condenser of a steam engine from the piston cylinder. Later, he would develop the sun and planet gear – which could provide a circular motion, thereby powering a wheel, which would then be used in transport and spinning.

He even created the unit, the horsepower, to show how strong his engine was by comparing it with the weight a group of ponies could lift. Such was his impact that Andrew Carnegie, in a 1905 book on the inventor, estimated that “in 1880 the value of world industries dependent upon steam was thirty-two thousand millions of dollars, and that in 1888 it had reached forty-three thousand millions of dollars.”

40 Elsie Inglis:

First World War nurse

When the Great War broke out and she applied to the Royal Army Medical Corp, Elsie Inglis received a letter back saying, “My good lady, stay home and sit still.” But Inglis, who was one of the first women to graduate from the University of Edinburgh, and set up her own medical practice in 1894, as well as a hospice for poor women, was not one for sitting still.

She persuaded the Scottish and National Women’s Suffrage Societies to fund women-run field hospitals, leading to the founding of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals for Foreign Services in 1914. She would be lauded by Winston Churchill as a “heroine who will shine in history”. Inglis and her team worked in Serbia, staying on when the Germans advanced and ultimately they were interned, working in a prisoner-of-war hospital.

Her unit was sent home in 1916, but she went out again later in the year to join Serbian troops in southern Russia. What it is believed Inglis already knew, but had told no one, was that she had cancer. While out there, she collapsed and sent a telegram home with the news, “Everything satisfactory and all well except me”.

On the day she landed in Newcastle in 1917, she stood to bid farewell to her Serbian staff, and collapsed. She died the next day.

39 Irvine Welsh: A Burns for our times

Irvine Welsh hurled a grenade into mainstream literature when he published in 1993 his uncompromising, gritty, yet wildly entertaining black comedy of junkies and lost souls in Edinburgh. Renton, Sick Boy, Begbie, Spud… you can’t live in Scotland and not know the characters. The Danny Boyle movie that followed, with its iconic poster, affirmed its place in global popular culture – and defined a new urban image of Scotland. It also created a new generation of stars, shooting Ewan McGregor into the stratosphere. Profane, intoxicating and written in Edinburgh vernacular, Welsh’s book had a blazing energy. Not everyone loved it. It was, according to Lord Gowrie, the chairman of the Booker prize panel, rejected for the shortlist after two judges deemed it offensive. A 2013 Scottish Book Week poll saw Trainspotting named Scotland’s favourite book of the last 50 years.

38 William Cullen: Inventor of refrigeration

Before fridges we had holes in the ground lined with straw and ice brought down from the mountains. We had to eat stuff immediately or cure it or ferment it. Ice harvesting was a huge business. Then, in 1756, William Cullen, one of the most important figures at the Edinburgh Medical School, devised a method of cooling through using evaporation of a liquid, which would absorb heat from the area it had come off. He didn’t make an actual fridge – it would take an American inventor to do that – but he pioneered the principles in 1748. Eight years later he did a public demonstration of artificial refrigeration in which he used a pump to create a partial vacuum in a container of diethyl ether – the result was that the liquid boiled. That reaction absorbed heat from the surroundings and produced a small amount of ice. The process is now an essential part of what the author of Chilled, Tom Jackson, has called “the cold chain”, which links our perishable food back to the farmer’s fields. The refrigerator, as Jackson says “has changed the way we live”.

37 Kirkpatrick Macmillan: Created the first bike

In the early 19th century, there were no bikes but people did ride on wheeled vehicles called hobbyhorses, propelling themselves along by pushing off the ground with their feet. Dumfriesshire blacksmith Macmillan decided to craft one in his smithy – and added horizontal pedals, whose movements were transmitted by cranks to a rear wheel by connecting rods. Macmillan’s bike was hard work, but in June 1842, he rode to Glasgow, in a trip that took two days and resulted in him being fined five shillings for mildly injuring a small girl who ran across his path. Macmillan didn’t patent his invention, or make any money out of it – it was others, like Gavin Dalzell of Lesmahagow, who copied it and did so. Author Gordon Irving, in his book, Devil on Wheels, describes Macmillan’s first run: “The villagers watched in total amazement as he lifted his feet to the pedals and went whizzing down the rough highway, the first person anywhere in the world to ride on a velocipede... The bicycle as we know it today had been born.” This simple piece of technology looks set to be more important as we are encouraged, in the interest of our fitness and for the sake of the planet, to get on our bikes.

36 John James Rickard Macleod: Physiologist who discovered insulin

It wasn’t Aberdonian John James Rickard Macleod’s own idea that there was something in the pancreatic secretions that might be involved in controlling blood sugar levels and deficient in those with diabetes. That notion came from surgeon Frederick Banting. But without Macleod’s input – he was an expert in carbohydrate metabolism running a lab at the University of Toronto – the discovery might never have come about. Macleod was, along with Banting, awarded the Nobel prize for the breakthrough. It saved the life of a 14-year-old boy who was the first human test subject for insulin treatment. Almost a century on we are in the grip of a global pandemic, with rates predicted to rise by 48% by 2045. Undoubtedly the lives of many millions more will be saved by insulin.

35 Dame Sue Black: Forensic anthropologist and crime fiction inspiration

Sue Black’s work led the way in human identification in conflict zones. Following her time as lead anthropologist for the British Forensics Team in Kosovo, she went on to provide assistance identifying the dead in Thailand after the Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004. She’s the great matriarch of forensics, and though she has now moved to Lancaster University, was responsible for setting up the ground-breaking morgue in Dundee and leading a revolutionary approach to forensics as head of the Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification at the University of Dundee. Plus, since they met on a radio show, she has been the forensic inspiration at the heart of crime queen Val McDermid’s works, the on-call expert who gives them their scientific grounding. Her book All That Remains, is a challenge to how we view death. “I wanted,” she has said, “to show that death has different faces – scientific, emotional, even hilarious. We think we’re expected to behave a certain way, but wouldn’t it be wonderful if, with our last dying breaths, what we hear is people laughing and singing rather than crying?”

34 John Muir: Conservationist behind the national parks movement

“Only by going alone in silence, without baggage, can one truly get into the heart of the wilderness,” wrote John Muir in a letter to his wife Louie in 1888. “All other travel is mere dust and hotels and baggage and chatter.” Born in Dunbar in 1838, Muir moved with his family to a Wisconsin farm, at the age of 11, and later studied botany and geology at university. Inventive by nature, he looked set for a career in industry, until he was temporarily blinded by a factory accident. Following that he decided to walk from India to Florida, drawing botanical sketches on the way. He enrolled himself in what he would call the “University of the Wilderness”. His wanderings would lead him to Yosemite valley where he got a job at a sawmill, and developed a theory that the valley had been carved by glaciers. Soon he was writing articles for leading magazines, which made him famous. Muir championed protecting some of the greatest areas of national beauty in North America. He lobbied for the creation of the Yosemite national park, and in 1903 he went on a camping trip with President Theodore Roosevelt, in which he persuaded the president to give the area extra protections.

33 Adam Smith: Father of modern free market economics

Adam Smith brought us the idea of an economics based around the twin ideas of “personal interest” and the “invisible hand of the market” – and those principles have been at the heart of much capitalist thinking since, though he himself never used the term capitalism. Smith’s Wealth Of Nations is considered one of the most important contributions to economic thought, and it was based around a new idea of the economy, forged in contrast with the prevailing principles of mercantilism of his time. It was generated in 18th century Scotland, where Smith, who was friends with David Hume, the geologist James Hutton, the chemist Joseph Black, was at the heart of enlightenment thinking.

One of the problems with Smith’s legacy is that we are often presented with this theory in a caricatured form. Yes, Smith was opposed to all laws and practices that tended to discourage production and increase prices. And, yes, at the heart of his thesis was the idea that an unregulated system would work because each person would try to maximise his or her benefit. But too often we are delivered that theory through the filter of the free-market fundamentalism of economists who followed, particularly the Chicago School. The wider scope of his moral philosophy is often omitted – his lamentations, for instance, on the potential social and moral ills of what he called “commercial society.” More and more now people are drawing attention to the concerns Smith had over inequality. As Nicola Sturgeon has put it, “Adam Smith is sometimes misquoted, misrepresented by some of his, what I would describe as, ultra-free-market supporters. Adam Smith, yes, knew that personal interest was a motivator of human behaviour. But, you can see in the Wealth of Nations that Adam Smith also knew and wrote that no country, no economy, could be fully successful if many of the people living within it were poor and we had inequality. So that’s the real legacy of Adam Smith.”

We live in times of questioning about capitalism, of a return in some countries, for instance Trump’s America, to a kind of neo-mercantilism. Are there still answers to be found in Smith? Many believe so. Jesse Norman, his biographer observes: “He has a vast amount to teach us, not merely about economics and markets and trade, but about the deepest issues of inequality, culture and human society facing us. Far from attacking Smith, we must turn to him again. For we cannot understand, or address, the problems of the modern world without him.”

32 Moses McNeil, Peter McNeil, Peter Campbell and William McBeath: Founding fathers of Rangers FC

Peter McNeil and Moses McNeil, aged 17 and 16, and Peter Campbell and William McBeath, both 15, discussed the possibility of forming a team during a walk through West End Park (now Kelvingrove Park) in March 1872. The club that has won 54 Scottish championships essentially started as a street team by a group of boys who had been smitten by the latest sporting craze of association football. They were joined in their endeavours by Tom Vallance, later to become a legendary Rangers captain, but who was then barely 16 years old.

The group called their team “Rangers”, having seen the name of a Swindon-based rugby club in an English Rugby Football Annual. Their triumph was to be the foundation stone of a Scottish institution. Rangers played their first ever match against Callander FC at Flesher’s Haugh on Glasgow Green in May 1872, which resulted in a 0-0 draw. Moses McNeil played for the club he helped found for 10 years, taking part in the 1877 and 1879 Scottish Cup finals and being a member of the first Rangers side to lift a trophy, the Glasgow Merchants Charity Cup in 1879. Historians now consider that Peter McNeil’s greatest contribution to the formative years of the club was off the field after his playing days. As match secretary, a position he held until 1883, he was in effect the club’s first manager. His administrative skills were recognised in 1886 when he became vice-president.

31 Brother Walfrid: Celtic FC founder

Andrew Kerins crossed the Irish Sea during the potato famine and settled in the east end of Glasgow in 1855, aged 15. After taking up the oath with the Marist Brothers in France, he eventually became a teacher and was assigned to Sacred Heart School in the East End to cater for the children’s spiritual and educational needs. He established the “penny dinner” and set up a boys’ clubs, before spotting the potential of football, which had fast been gaining in popularity in the late 19th century, to raise money by attracting paying customers.

During a meeting at St Mary’s Church hall in the Calton area on November 6 1887, with little fanfare (apart from a constitution penned by the meticulous Brother Walfrid), “the Celtic” was formed. It was intended to “supply the East End conferences of the St Vincent De Paul Society with funds for the maintenance of the ‘Dinner Tables’ of our needy children in the Missions of St Mary’s, Sacred Heart, and St Michael’s. It is therefore with this principle object that we have set afloat the Celtic”. Although formed to raise money for the needy of the East End who were mainly Catholic and Irish, the new club would be neither exclusively Catholic nor Irish. Walfrid remained a largely forgotten figure for much of the 20th century but in the late 1990s as interest in the so-called “Irish diaspora” burgeoned there was renewed attention too on the man who did so many good works in Glasgow. A man who changed tens of thousands of Catholics’ lives for the better and, through his enduring legacy, Celtic, tens of millions.

30 Jackie Stewart: Formula One driver and safety advocate

From mid-1968 until his retirement at the end of 1973, Sir Jackie Stewart was the undisputed number one and everyone knew it. As well as his unquestioned driving skills – 27 grand prix wins in 99 races and three world championships – this Milton-born legend championed safety in the sport and was the first to wear a seatbelt, insisted circuits should be lined by barriers and called for fire-resistant clothing. When it was called for, the Flying Scot, as he was known, led driver boycotts.

Attitudes to safety were very different in the 1960s and early 70s, and Stewart was vilified for his stance. But he didn’t care and his one-man safety crusade made the sport much safer. The catalyst for Stewart’s safety campaign was an accident he suffered in the 1966 Belgian Grand Prix, when he was left trapped in an upturned car with fuel leaking out and was stuck for 25 minutes before being rescued. He also recalled counting 57 deaths while he was racing. Many were friends. “So many people were killed during that period,” he said. “The only way I can relate to it, thinking back, is that it must have been like World War Two and the Spitfires and Hurricanes leaving the south coast of England to stop the German Luftwaffe. They were losing their colleagues on a regular basis. And so were we.” Despite turning 80 this year, Stewart has not slowed down and is the founder of Race Against Dementia, a charity established to fight against the as yet incurable disease that his wife, Lady Helen, suffers from.

29 Mairi Mhor Nan Oran (Big Mary of the Songs): Gaelic songstress and political campaigner

Mairi was born in March 1821 at Skeabost on Skye, the daughter of a crofter. When she was about eight the family, following an abortive attempt to emigrate to Canada, settled in Glasgow; returning to Skye some 12 years later. Mairi left in about 1844 and went to Inverness where she married Isaac MacPherson in 1847. After her husband’s death in 1871 she earned her living as a nurse. During this period she was accused of stealing clothing from her employer and imprisoned. She always protested her innocence and her bitterness at the injustice which she had suffered left a deep impression upon her.

Upon her release from prison in 1872 she went to Glasgow, where she underwent formal training as a nurse before going on to become a district nurse in Greenock. Her talent for Gaelic poetry and ability for storytelling made her socially and politically significant in Glasgow. She became a focal point amongst the ‘exiled’ Highlanders in Glasgow and Greenock, and she was present at number of gatherings there. She returned frequently to Skye, finally settling there in 1882. During her time in the Lowlands she had become deeply involved in the Land Agitation movement and she continued to attend meetings in the islands and on the mainland. She also accompanied Charles Fraser Mackintosh on several trips on behalf of the movement. Mairi vigorously opposed the treatment and disenfranchisement of Skye crofters and wrote songs directed at those she held responsible and the indifference of those unwilling to act.

28 David Hume: philosopher

David Hume was a Scottish philosopher, historian and essayist known for his radical philosophical scepticism and empiricism. He believed that passion rather than reason governed human behaviour and that human knowledge was solely based on human experience. Hume was born on February 24, 1711, in Edinburgh. His father died when he was an infant, leaving him and his two older siblings in the care of his mother. Hume went with his older brother to the University of Edinburgh in 1723.

He began his literary journey with his masterpiece, A Treatise of Human Nature while he was living in France for three years. Though the book was widely discarded and written off by the critics then, it is today considered as one of the post important works on the history of Western philosophy. Hume found success only later in his life when he turned into an essayist. His job as a librarian in the University of Edinburgh helped him access a lot of research materials which provided him the guided information for his massive six volume masterpiece, ‘The History of England’. The book earned favourable response and became a bestseller. It was considered as a standard history of England during its time.

27 Charles Rennie Mackintosh Designer and architect

The Glasgow-born artist and architect attended evening classes at Glasgow School of Art while working as an apprentice to architect John Hutchison. It was through the School of Art that in 1888 he gained his first commission as a professional, and won a prize from the Glasgow Institute of Fine Art, for a design for a terraced house. Between 1890 and 1910 most of the classic buildings associated with Mackintosh emerged. The Glasgow Herald Building was completed in 1895; Ruchill Free Church Halls were completed in 1899; Queens Cross Church opened for worship in 1899; Kate Cranston’s Willow Tearooms opened in 1903; Hill House in Helensburgh was completed in late 1903; The Glasgow School of Art was completed in stages between 1897 and 1909; The Scotland Street School was completed in 1909; and The House for an Art Lover was designed in 1901, though it was not built until the 1990s.

Mackintosh’s attention to detail was fanatical: in the Scotland Street School, for example, hot water pipes were routed below the coathooks, meaning that pupil’s coats were warm and dry at the end of the day. But this attention to detail, which some have attributed to borderline autism on Mackintosh’s part, also meant that the projects he led were seldom if ever profitable. Never as successful or as recognised in his day as he should have been, he has since gone on to become an hugely influential icon, a superstar of the design world.

26 David Livingstone: Missionary and explorer

Livingstone became a great hero of the Victorian era for his epic discoveries in the heart of unexplored Africa. He spent the last six years of his life almost cut off from the outside world, refusing to leave his beloved Africa. From an early age, he was fascinated with geology, science and the natural world. He had to work long hours in a local cotton mill from the age of 10 to 26. His work in the mills imbued him with a classic Protestant work ethic; this experience left him with respect and empathy for workers.

In 1836, he entered Anderson’s College in Glasgow to train as a medical missionary. Due to the outbreak of war in China, it was suggested Livingstone travel to Africa to work as a missionary there. Livingstone had great success as an explorer partly because of his ability to get on with tribal chiefs. He travelled lightly without soldiers, and this non-confrontational approach made it easier for him to be welcomed. On these expeditions, he preached a Christian message but did not force tribal chiefs to accept it, unlike some of his contemporaries. One year before his death, Livingstone was met by a correspondent from the New York Herald, Henry Morton Stanley. Livingstone had been lost in the heart of Africa for six years – his letters rarely getting through. It is said that Stanley famously found Livingstone in Ujiji on the shores of Lake Tanganyika on October 27 1871. He greeted Livingstone with the famous refrain: “Dr Livingstone, I presume?”

25 Fanny Wright: Feminist and social reformer

Frances Wright was one of three children born in Dundee to Camilla Campbell and James Wright, a wealthy linen manufacturer and political radical. Both of her parents died young, and Fanny (as she was called as a child) was orphaned at the age of three, but left with a substantial inheritance. An aunt acted as guardian for both Fanny and her sister Camilla. Wright was brought up in the homes of relatives, including James Milne, a member of the Scottish school of progressive philosophers. Milne, who encouraged Fanny to question conventional ideas, was to have a lasting influence on her development.

She was to go on to tour the US extensively and was appalled by the practice of slavery. She decided to establish a colony in which slaves could be emancipated. She believed that slaves would work harder for their freedom than they would for a master, and therefore expected the colony to be self-supporting and to provide funds for the purchase and training of additional slaves. Due to the effect hard labour at the settlement took on her health, she went abroad to recover. She was later forced to abandon her plan, after spending her personal fortune on it.

In the late 1820s Wright was the first woman lecturer to speak publicly before gatherings of men and women in the United States about political and social-reform issues. She advocated for universal education, the emancipation of slaves, birth control, equal rights, sexual freedom, legal rights for married women, and liberal divorce laws. Wright was also vocal in her opposition to organised religion and capital punishment.

24 Sir Walter Scott: Writer

From his earliest years, Scott was fond of listening to his elderly relatives’ accounts and stories of the Scottish Borders, and he soon became a voracious reader of poetry, history, drama, and fairy tales and romances. In 1802 he published his first literary work, Minstrelsy of the Scottish Borders. It was his second work which made his name, however; The Lay of the Last Minstrel (1805) was an immensely successful poem. Scott followed this with further romantic poems, such as Marmion (1808) and The Lady in the Lake (1810).

In the decade between 1810 and 1820 Walter Scott published a succession of hugely popular historical novels, beginning with Waverley (1810), Guy Mannering (1815), and Ivanhoe (1819). These books, and others that followed in the 1820s, were published anonymously or under pseudonyms. It was not until 1826 that the author was revealed to be Sir Walter Scott. He helped popularise the historic novel as a literary genre, and influenced generations of future writers.

23 Robert Louis Stevenson: Novelist

From a very early age, RLS was spinning stories. As a child – he was born in Edinburgh in November 13 1850 – he suffered from chronic bronchial disease, and spent much of his childhood alone in bed making up tales. Trained first as an engineer and then as a lawyer, he was always more interested in writing, imitating authors he admired and then, from 1873, publishing essays and working on plays.

Conflicted with his father over both religion and earning a living, he led a bohemian life in Edinburgh and took walking tours in Britain and abroad.

In 1876, he met the love of his life, the lively American Fanny Van de Grift Osbourne. In 1879, he followed her to California, where they married after Fanny’s divorce; The Silverado Squatters (1884) is the story of their honeymoon in an abandoned mining camp. Stevenson’s fame grew with the publication of Treasure Island (1883), and in 1884 he and Fanny moved to Bournemouth, where they lived for three years. During this period he wrote Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and Kidnapped (both published 1886). He died from a brain haemorrhage working on his very Scottish masterpiece The Weir of Hermiston.

22 Thomas Telford: Godfather of civil engineering

Thomas Telford was born near Westerkirk, Dumfries, in 1757, the son of a poor shepherd. He apprenticed for a time to a stonemason in Langholm, and worked on the construction of Edinburgh’s Newtown, before moving to London in 1782 in search of work. There he helped design and build Somerset House, and later moved to Portsmouth as manager of works at the dockyards. He was responsible for the construction of the Ellesmere Canal in 1793, and the Severn Suspension Bridge at Montford (1790).

His success led to a government appointment to survey the roads in rural Scotland as part of a major transportation improvement scheme. His survey results were accepted and Telford was asked to oversee the construction of some 1,000 miles of roads and 120 bridges – a job which took him over 20 years to complete. Also in Scotland, Telford worked on dock improvements in Wick, Aberdeen, Peterhead, Leith, and Banff, as well as the Caledonian Canal project linking a series of freshwater lochs with 20 miles of canals. His use of the cast iron arch bridge at Craigellachie in Strathspey and the Waterloo Bridge in Wales turned structure into a form of art. In 1818 Telford helped found the Institute of Civil Engineers, and he served as its first president.

21 Alex Salmond:

One of the most significant political figures of recent history

It is difficult to exaggerate the importance of Alex Salmond to the Scottish National Party. He was responsible not just for hauling the SNP from the fringes of Scottish politics to become a party of government, but also for forming a majority SNP administration at Holyrood and holding a referendum on Scottish independence. Alexander Elliott Anderson Salmond joined the SNP in 1973, while still a teenager. He went on to become a rising star of the party, winning the Westminster seat of Banff and Buchan in 1987 – and notably getting himself banned from the Commons chamber for a week after interrupting the chancellor’s Budget speech in protest at the introduction of the poll tax in Scotland. When the SNP leadership job came up in 1990, Salmond grabbed the opportunity and repositioned the party as more pro-European. He resigned in 2000, for reasons which remain largely unexplained, but came back again as leader in 2004, to mould his party as a more focused force.

Confronted with a combative – some might say brash – SNP leader, Scottish Labour imploded, losing a series of leaders, and found itself out of power in Westminster too. Following his leadership comeback, on a joint ticket with deputy Nicola Sturgeon, Salmond led the SNP to what was then its greatest hour – victory at the 2007 Scottish election and delivery of a minority SNP government. He went on to lead the party to a landslide victory in 2011. The nationalists’ victory brought about a generational shift in Scotland, where Labour had been the dominant force.

The result made the independence referendum a certainty and the first minister, along with his government and the wider independence movement, set out a vision of Scotland’s as one of the world’s richest small nations – with opponents arguing he was willing to say anything to win a “Yes” vote. But on the night it wasn’t to be, as voters rejected independence by 55% to 45% on September 18 2014. Salmond stood down as First Minister and SNP leader the next day. He faces nine charges of sexual assault and two of attempted rape, which he denies.

Tomorrow: The top 20 Scots

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel