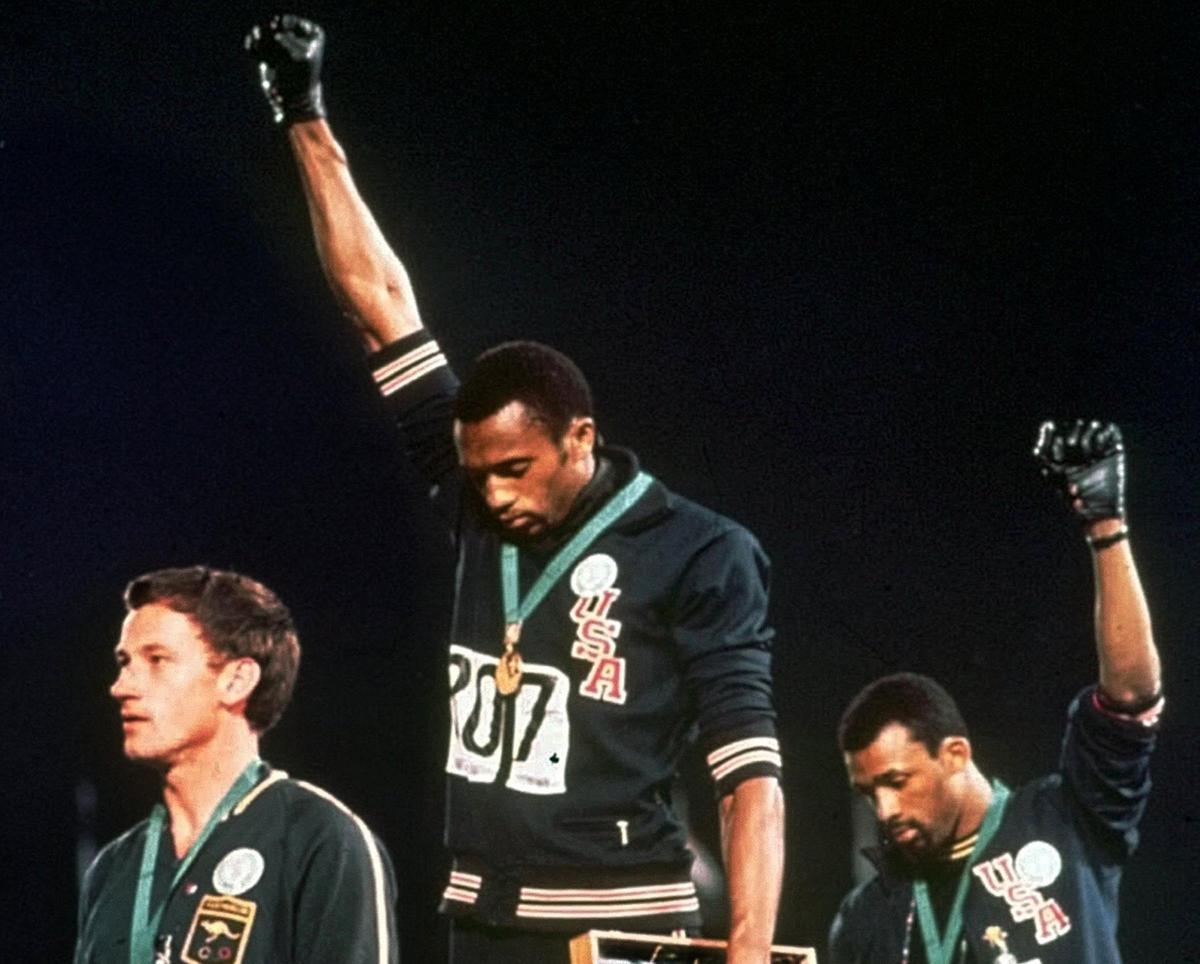

It had been the fastest 200 metres race of all time, the first to shatter the 20-second barrier. Two Americans, split by an Australian in second place, now standing on the winners’ podium, their heavy medals round their necks. As the first notes of the Star Spangled Banner echoed round the stadium the two Americans bowed their heads and raised black gloved fists. After a few seconds, as realisation about what the protest meant dawned, after the awed hush came the boos and jeers.

Forty years later the winner, Tommie Smith, called what was perhaps the most iconic, powerful and shocking protest – certainly the first on prime-time television – a cry for freedom and human rights. “We had to be seen because we couldn’t be heard,” he said.

It was on October 16, 1968, at the summer Olympics in Mexico City and it came against a background of worldwide agitation and resistance. Racial tensions were boiling, the US civil rights rights movement had morphed into black power, it was just months after the assassination of Dr Martin Luther King in Memphis, nightly news footage of US soldiers embroiled in the Vietnam war was turning the American public against continuing it and it was taking young people into clashes on the streets. In France, revolution was abroad as students and workers staged protests and strikes.

Smith and John Carlos, who was to come third in the race, were frustrated by the passive and incremental nature of pressure for racial equality and change, and decided on dramatic action. They had formed the Olympic Project for Human Rights and they saw the Olympic Games, watched by the world, as the perfect venue to to get it off the blocks.

They wanted better treatment, not just for black athletes but black people around the world. They demanded the hiring of more black coaches and the rescinding of invitations to apartheid states Rhodesia and South Africa. They had considered boycotting the Olympics entirely but, mulling it over, decided that a protest which would be seen in every corner of the planet would achieve much more.

As the teams arrived in Mexico for the Games violent streets demonstrations were taking place in the streets against the government. The military had gunned down hundreds of peaceful students at Tlatelolco Plaza in the city. Then 10 days before the Games were due to open an unarmed group of protestors gathered in Three Cultures Square to plan the next phase of the students’ movement. The government sent in bulldozers to disperse the thousands gathered there, accompanied by troops who fired into the crowd killing, depending on whether you believe the official or unofficial account, either four or several hundred young protestors.

Carlos and Smith were deeply affected. Their commitment hardened. The two Americans, with the white Australian Peter Norman, were the fastest in the world. Before the race they told Norman what they planned. He was a working-class boy from Melbourne, whose parents were members of the Salvation Army, and he believed in equality. He volunteered to wear an Olympic Project badge.

Smith and Carlos had decided to appear on the podium without shoes and wearing black socks, to bring attention to black poverty, beads to protest lynchings and the iconic black gloves to signal support with black and oppressed people around the world.

“I looked at my feet in my high socks and thought about all the black poverty I’d seen from Harlem to East Texas,” Carlos wrote later. “I fingered my beads and thought about the pictures I’d seen of the ‘strange fruit’ swinging from the poplar trees of the South.”

But as they made their way to the podium Carlos realised he had forgotten his gloves, Norman suggested they share a pair, so Smith raised a black-gloved right fist and Carlos the left as the national anthem rang out.

After the ceremony the two US athletes were rushed from the stadium, suspended from the team and kicked out of the Olympic Village, returning to the America to find themselves facing a massive backlash, including death threats. Later on they were slowly re-accepted into the Olympic movement, both going on to have successful careers in professional football.

Not so Norman. Australia had its own racial problems, a "white Australia policy" which basically limited immigration to white people, turning down non-European migrants. The original Aboriginal people had also been historically oppressed. The Australian sports establishment ostracised Norman. Although he qualified for the Olympic team repeatedly, posting by far the fastest times, he was not picked for the 1972 Games. Instead the country did not send a sprinter that year.

Norman retired from athletics and slumped into depression, alcoholism and painkiller addiction. His bulky silver medal was not reclaimed but, perhaps in a comment on the Australian sporting establishment, he used it as a doorstop.

His name was virtually airbrushed from history, he was regularly excluded from events and even when the Olympics came to Sydney in 2000, more than 30 years later, he was not recognised. It would take 12 years for the Australian Government to formally apologise.

“I won a silver medal,” Norman said, “But really, I ended up running the fastest race of my life to become part of something that transcended the Games.”

Norman died in 2006; Smith and Carlos were pallbearers at his funeral.

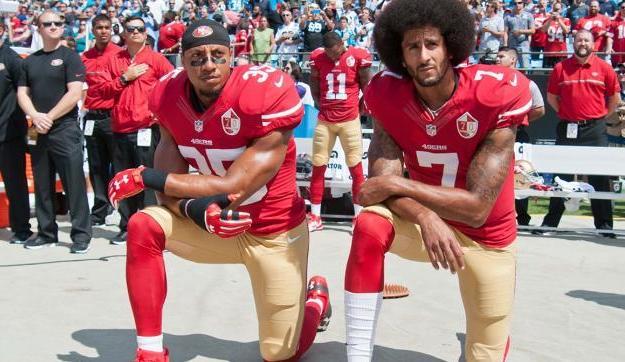

The two former track stars continue to campaign and support other protesting athletes, including the San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick who started the “take a knee” protest during the national anthem to highlight police brutality against black people, including fatal shootings. Several other American footballers joined him but, as a result, the NFL passed a rule that anyone who did would be heavily fined. Kaepernick was released by the 49ers, but despite being a free agent none of the 32 teams has moved to sign him.

Muhammad Ali is one of the best-known US athletes to take a major political stand. When he won a gold medal at the 1960 Olympics he claimed that he threw it into the Ohio River after he was refused service in a restaurant. And he famously refused to fight in Vietnam, saying “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong.”

Football in the UK has been plagued by racist incidents. Last December a banana skin was thrown at Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang after he scored for Arsenal. In the same month Manchester City’s Raheem Sterling suffered racial abuse in a game against Chelsea. In April Troy Deeney and Watford team-mates Adrian Mariappa and Nathan Byrne were racially abused on social media.

Scotland, of course, is not immune. Just last month the Hearts striker Uche Ikpeazu claimed that he was racially abused by Hibs fans during the derby at Easter Road.

Fraser Wishart, head of the players’ union, warned in December that racism may never be stamped from the game. He spoke out as two players – Hearts’ Arnaud Djoum and Aberdeen’s Shay Logan – rounded on racists and demanded action to curb the abuse.

Hearts issued indefinite bans on two fans after Motherwell’s Christian Mbulu was racially abused last weekend. Celtic’s Scott Sinclair was also racially abused by Aberdeen fans at the League Cup Final last year.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel