He was the ultimate genius and just his name itself is guaranteed to sell tickets with 10.2 million visitors a year visiting his most famous work a year alone.

Now 80 drawings by the Renaissance polymath Leonardo da Vinci are coming to Scotland next month – many for the first time.

The exhibition is to mark the 500th anniversary of the death of da Vinci, and the Renaissance master’s greatest drawings will go on display at The Queen’s Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse, in the largest exhibition of the artist’s work ever to be seen in Scotland.

The Queen has one of the greatest collections of his drawings.

Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing explores the full range of da Vinci’s interests – painting, sculpture, architecture, anatomy, engineering, cartography, geology and botany – providing a comprehensive survey of his life and an insight into the workings of his mind.

Revered in his day as a painter, da Vinci completed only around 20 paintings. He was respected as a sculptor and architect, but no sculpture or buildings by him survive. He was a military and civil engineer who plotted with Machiavelli to divert the river Arno, but the scheme was never executed.

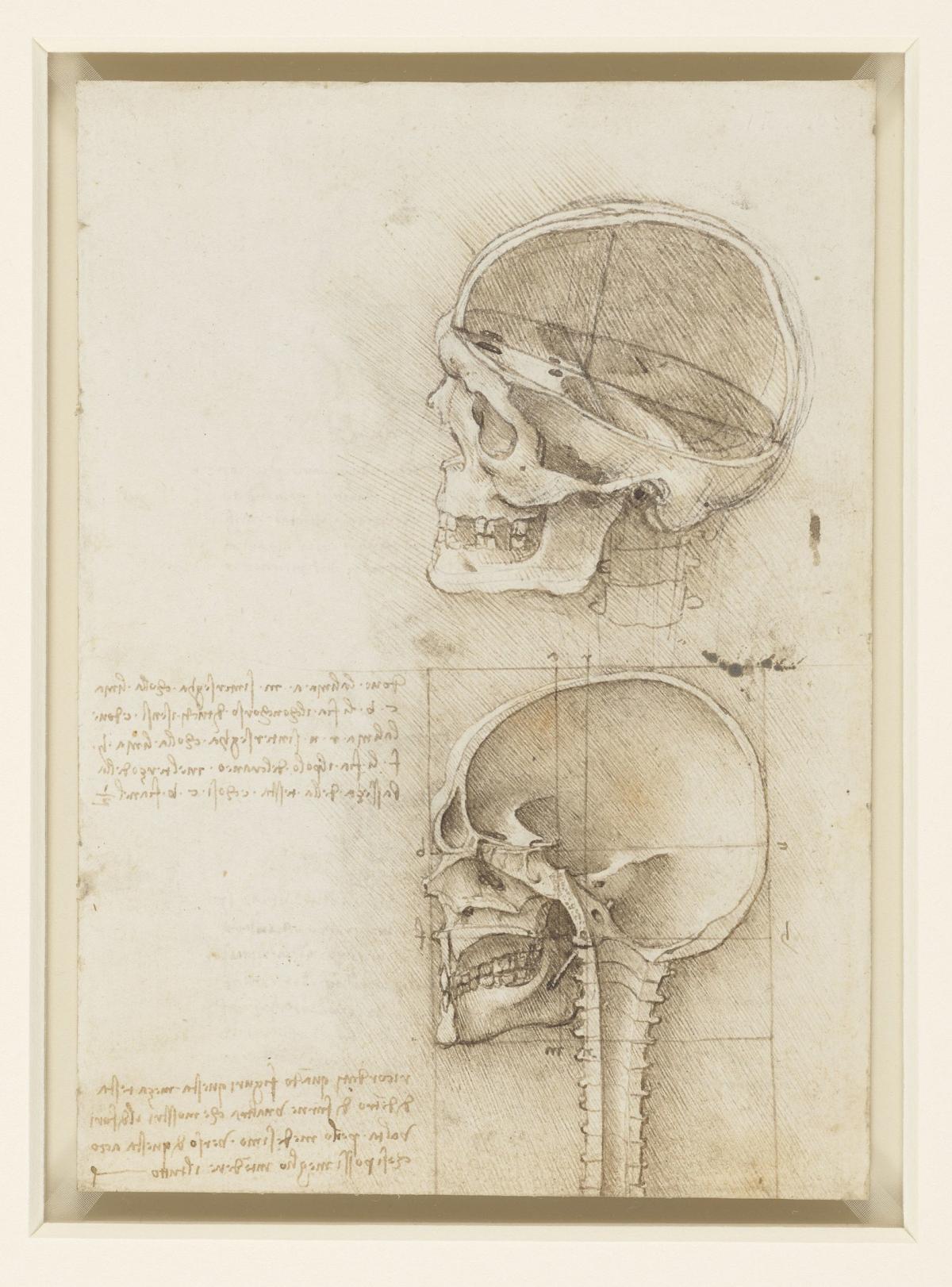

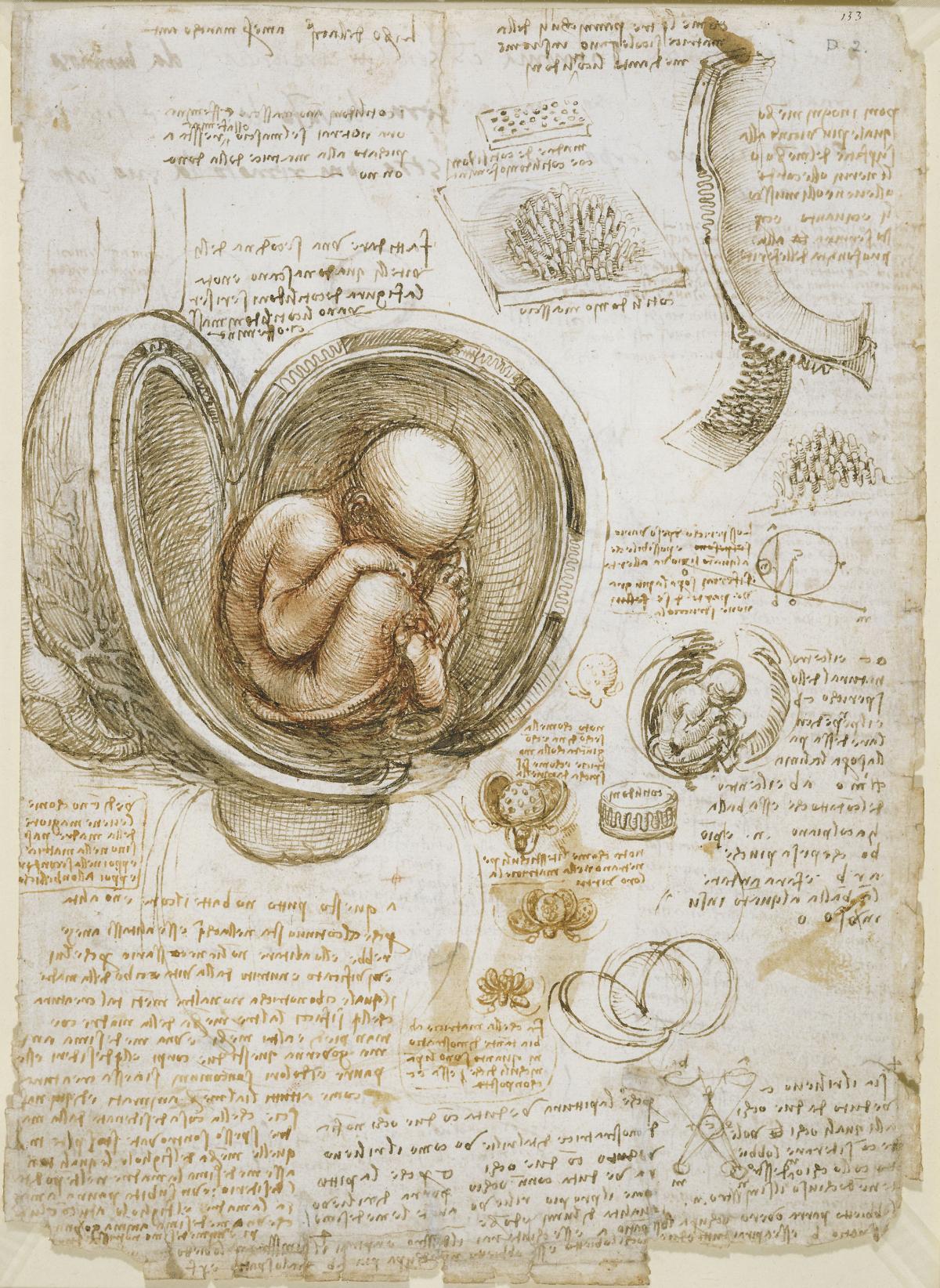

Da Vinci was also an anatomist and dissected 30 human corpses.

But his groundbreaking anatomical work was never published – and he planned treatises on painting, water, mechanics, the growth of plants and many other subjects, although none was ever finished.

“As so much of his life’s work was unrealised or destroyed, Leonardo’s greatest achievements survive only in his drawings and manuscripts,” say the Royal Collection Trust.

“The drawings by Leonardo in the Royal Collection have been together as a group since the artist’s death in 1519, and entered the Collection during the reign of Charles II, around 1670.

“Leonardo firmly believed that visual evidence was more persuasive than academic argument, and that an image conveyed knowledge more accurately and concisely than any words.

“Few of his drawings were intended for others to see: drawing served as his laboratory, allowing him to work out his ideas on paper and search for the universal laws that he believed underpinned all of creation.

“In the breadth of his interests, Leonardo was the archetypal ‘Renaissance man’, and his work is characterised by a multitude of artistic and scientific pursuits that cross-fertilised each other over many years.”

Da Vinci’s research into the human body stemmed from a desire to be “true to nature” in his painting, and in time anatomy became his greatest scientific pursuit.

Though he never completed his planned treatise on the subject, da Vinci’s later anatomical studies mark him out as one of the great scientists of the Renaissance.

The exhibition includes some of the finest examples of the artist’s anatomical drawings, including The skull sectioned (1489), The fetus in the womb (c.1511) and The cardiovascular system and principal organs of a woman (c.1509–10).

“Drawings of horses abound throughout Leonardo’s work, including studies for three equestrian monuments that were never realised,” said the trust. “The sculpture that would have been his masterpiece, a monument to Francesco Sforza, the late Duke of Milan, fell victim to the turbulence of politics and warfare that was a constant shadow over Leonardo’s career.

“Studies for the monument, which would have been the largest bronze cast in Western Europe since antiquity, include A design for an equestrian monument (c.1485-8) and Studies of a horse (c.1490).”

The natural world is explored by da Vinci through detailed landscapes, studies of water and in numerous botanical studies, the finest of which were developed in preparation for the now lost painting Leda and the Swan, including A branched bur-reed (c.1506-12).

The artist’s Leda was the only female nude that he ever painted, and the nakedness of her body was emphasised by her elaborate hairstyle of braids and coils, the focus of the preparatory study The head of Leda (c.1505-8).

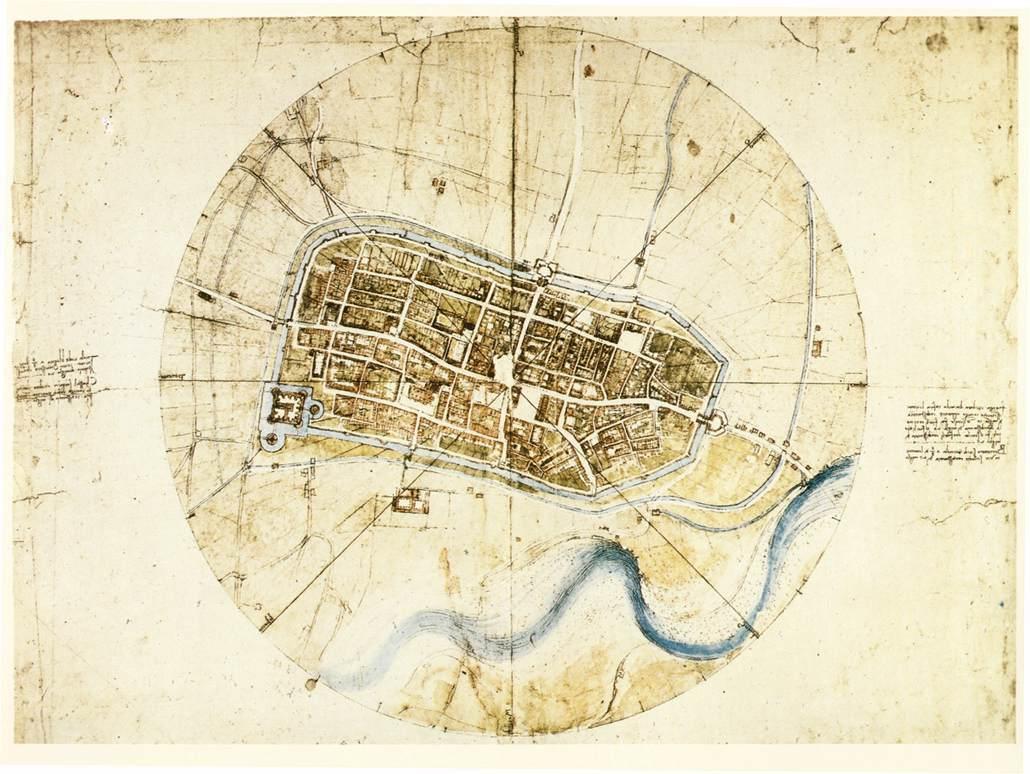

Da Vinci gained a reputation as a skilled map-maker and engineer, and in August 1502 he was appointed military architect and engineer to Cesare Borgia, son of Pope Alexander VI and Marshal of the Papal Troops.

Over the next few months, Leonardo surveyed Borgia’s strongholds to the north and east of Florence, and created his most impressive surviving map, A map of Imola (1502).

He continued to make maps on his return to Florence, several of which were connected with his proposed projects in civil engineering, including a map of the Valdichiana (c.1503-6) and The Arno valley with the route of a proposed canal (c.1503-4).

His most famous work is the Mona Lisa, which hangs in the Louvre in Paris.

Towards the end of his life, da Vinci left Italy forever and moved to France.

His body was failing, and in his late drawings and writings he became obsessed by the subject of a cataclysmic storm overwhelming the Earth and sweeping away all matter.

But far from being chaotic, these deluges were drawn and described with the dispassionate eye of a scientist.

The most elaborate is A tempest (c.1513-18), in which wind gods hurl thunderbolts among dense clouds, while a landslide peels away from the remains of a mountain and falls into the rushing waters below.

The exhibition in Edinburgh is the culmination of a year-long nationwide event, which has given the widest-ever UK audience the opportunity to see the work of this unparalleled artist.

In February, 144 of da Vinci’s drawings from the Royal Collection went on display in 12 simultaneous exhibitions at museums and galleries across the UK, attracting more than one million visitors.

Martin Clayton, head of prints and Drawings at the Royal Collection Trust, said: £The drawings of Leonardo da Vinci are both incredibly beautiful and the main source of our knowledge of the artist.

“As our year-long celebration of Leonardo’s life draws to a close with the largest exhibition of his work ever shown in Scotland, we hope that as many people as possible will take this unique opportunity to see these extraordinary works, and engage with one of the greatest minds in history.”

Admission is £7.50 for adults and £3.80 for under 17s.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here