THE Troubles aren’t over. Ask Michael Pike, who’ll tell you about the film he watched recently and how it brought back memories of the time he held a gun to a man’s face and nearly pulled the trigger. “I found myself getting really f****** angry,” he says. “I had to draw the curtains and open a can of beer and think: tomorrow is a new day.”

Or ask Helen Whitters, who’ll tell you about the secret British Government file that has her son’s name on it. He was killed by a plastic bullet in Londonderry/Derry nearly 40 years ago but she still hasn’t seen what the file contains. She wants to know, once and for all, what really happened in the past, and she fears for the future. “People are really worried in Northern Ireland,” she says.

And ask Ian Wood, who will talk about the recent fire attack in which a pub was destroyed, and the young men who enjoy strutting their stuff in the flute bands, on both sides. “It’s a disturbing development,” he says. “There’s still the sense of unfinished business.”

All of these stories are about Northern Ireland, but they are stories about Scotland too. Michael Pike grew up in Glasgow. Helen Whitters has lived for most of her life in Clydebank. And the pub that was burnt out last month, it isn’t in Londonderry/Derry or Belfast, it’s in Govan. The connections between Northern Ireland and Scotland are deep and old, and sometimes troubling, and they are still exerting their influence.

Both Michael Pike and Helen Whitters know the connections well because they’ve lived them. The Troubles were something they experienced every day. Still do. But their experiences reveal the bigger story too: how Northern Ireland has affected Scotland, and the role Scots played in the Troubles. Many Scottish families suffered direct bereavement. Some Scots saw themselves as brothers-in-arms with their comrades over the water. And during the Troubles, around 40,000 Scottish military personnel served in Northern Ireland, often experiencing the worst of the fighting.

Michael Pike, known as Spike, was one of those soldiers, and his story reveals a lot about what the troops faced in Northern Ireland. It also, thankfully, offers some hope. Michael was born in 1960 and grew up in a council house in Milngavie. His father was English, his mother was from Yoker, and he says his childhood was pretty rough at times. His father was violent and Michael remembers tiptoeing round the house trying not to provoke him.

As for religion, Michael’s mother was Protestant but he says it wasn’t until primary school that the religious divide was thrust upon him. Orange walks would break out in the playground. The Catholic kids from up the road would pick on him. He remembers putting a brick in his bag and hitting one of the Catholic boys with it. Problem solved, he says. It was just cat calls after that.

By the time of secondary school, Michael had pretty much rebelled and the army began to look like a good option: the travel, the adventure. “You get caught up with the bullshit romance of it,” he says, although he was turned down at first. “I had an assault charge by that point and God forbid they let violent people in the army.”

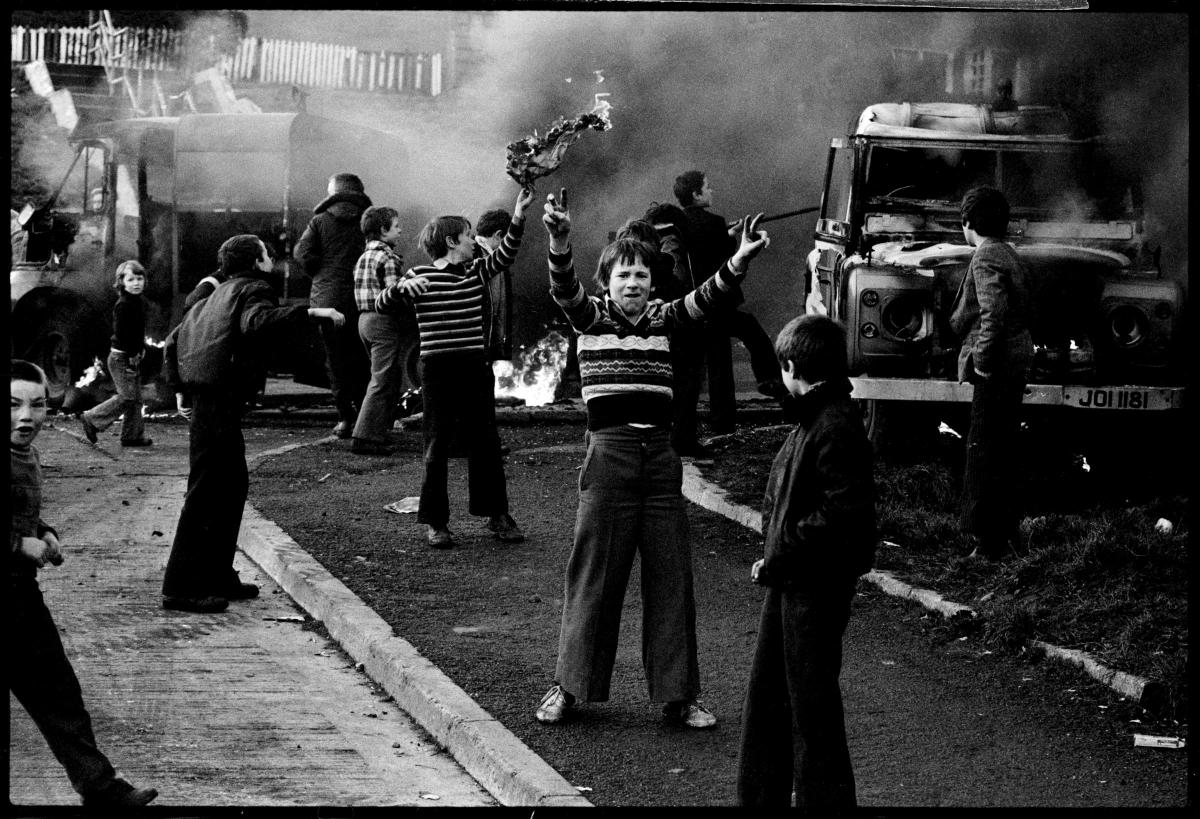

Eventually, though, he was accepted and joined the Scots Guards in the late 1970s – at a time when Scottish regiments were at the sharpest end of the conflict in Northern Ireland. If there had been some goodwill when British troops were first deployed in the late 1960s, then it was long gone by the time Spike arrived. Scottish soldiers had been accused of brutality during a crackdown imposed on the Falls Road, and on 10 March 1971, the Provisional IRA murdered three unarmed soldiers of the 1st Battalion, Royal Highland Fusiliers. The legacy was poisonous and for many Scottish soldiers, there was a sense that the peacekeeping mission was over. It was now about getting even. For many other Scots watching from afar, it changed the atmosphere. It opened up a sore.

Michael also wasn’t prepared for the level of hatred that would come his way. “Kids would throw bricks or anything they could get their hands on. Old women would spit at me and call me a Brit bastard; people would set dogs on you. And my defence mechanism to that level of hate was to hate them back. They became the enemy.”

Back home, some other Scots were feeling the same way, and were prepared to take action. Money was raised here and sent to Northern Ireland to fund both Loyalist and Republican terrorists; other Scots took more direct action and smuggled arms into the province; a protest movement under the banner “Troops Out” also developed and held demonstrations in Scotland. There was anger in Scotland and it was partly because the people involved in the Troubles were from the same stock – they were brothers, sisters and cousins; other Scots just wanted to demonstrate their commitment to Loyalism or Republicanism.

Even though he was a soldier, Michael Pike felt some of this affinity with the people of Northern Ireland as well. Here he was, a working class lad from a council house in Glasgow and he was pointing guns at men who were a bit like him, and he sometimes felt the connection. “It was unconscious,” he says. “I wouldn’t say in front of the other lads.” He remembers guarding a young man called Brendan Davison, who was later shot dead by the UVF. It was just Michael and him and a gun in a room. “I was looking at this guy,” says Michael, “and I thought, this is mad. This is like a dictatorship within a democracy.”

In a way, Helen Whitters felt something similar, especially when she was regularly stopped and searched by the military in her home city of Londonderry/Derry. For a time, Helen, her husband Des, and her young son Paul lived in Clydebank, but they returned to Londonderry/Derry in the mid-1970s when there was a ceasefire and they thought things were looking up. They were wrong. A few years later, the hunger strike of Bobby Sands in 1981 provoked rioting and Helen’s son Paul, by then 15, was there. There was a knock at the door and a boy told Helen, "your son has been hit with a plastic bullet".

He died 10 days later.

For years afterwards, Helen couldn’t bear to talk about what happened. “I didn’t want to know that a gun fired at 160 miles per hour and that someone fired that at my son’s head,” she says. But now she is campaigning to see the file that the British Government has on her son’s death. It is marked “sealed until 2059”. Helen is 73.

Eventually, it was all too much for Helen. She was trying to keep things from her younger son Aidan, her marriage broke down, and she decided to come back to Glasgow, where she has been since. “I had to choose,” she says, “and it was the best thing I could do at the time. I know we have a problem with sectarianism and football and all the rest of it in Scotland, but it’s still better than Northern Ireland.”

There was never a complete escape from the Troubles in Scotland, though. In December 1971, the UVF detonated a bomb at McGurk's Bar in Belfast; the explosives came from Scotland. Eight years later, the UVF bombed two Catholic pubs in Glasgow, the Old Barns in Calton and the Clelland Bar in the Gorbals. And in 1981 a bomb was detonated at the Sullom Voe terminal in Shetland during a visit by the Queen. It was attributed to the IRA. There were no injuries in these attacks.

Ian S Wood, the historian and writer who has contributed to a new BBC documentary about the Troubles, says that in many ways Scotland was lucky not to have suffered worse attacks. He speculates on what might have happened if there been a Birmingham-style bombing in Glasgow on a Saturday night. “It’s not too pretty to think what the backlash might have been to that,” he says.

“The amazing part of it is it could have been far more toxic and dangerous for Scotland than it proved to be,” he says. “The potential was there for the whole thing to have been very divisive and dangerous in Scotland, but things stayed under control. A crucial factor was the Provisional IRA never undertook offensive operations in Scotland or hardly ever. I have never found the proof the Provisional IRA had a standing order forbidding bombings in Scotland – it’s often said and I’ve heard Republicans say it and I don’t doubt it.”

Even so, Ian Wood says Scotland was fortunate to escape a fatal attack – there were rogue units of the IRA and militant loyalists who could easily have struck; the impact in Scotland also runs deep in other ways. Sixty-three Scottish soldiers were killed in Northern Ireland during the Troubles. Ian Wood is also concerned that the Troubles, 50 years on from their beginning, are fuelling sectarianism. He mentions last month’s suspicious fire at the Tall Cranes pub in Govan, which was a base for a Republican flute band.

“There are young men in Scotland who still like to think themselves as keepers of the flame, be they Loyalist or Republican,” he says. “And the fact that the Loyalist bands in Scotland are stronger than they have ever been, that’s a product of the Troubles, without a doubt. I think for a lot of people in Scotland, a very vocal body of opinion at Celtic games, there’s still the sense of unfinished business.”

Ian Wood is also concerned, as are Michael Pike and Helen Whitters, about the possible effects of Brexit on the peace process. Michael says there are people on both sides who would go back to using the gun and the bomb and he cites the death of Lyra McKee, the journalist who was shot in Londonderry/Derry after violence broke out during police searches.

Michael says he is determined to do what he can, though, to work towards continued reconciliation rather than violence and has become active in the campaigning group Veterans for Peace. His activism is also partly about coming to terms with his own experiences, the after-effects on his mental health, and his role in the military.

He tells me about the last day he spent in Northern Ireland as a soldier, driving towards the airport with the words of Republicans on the street ringing in his ears: “We’ll get one of you”. He made it out alive, but the emotional effects were profound. “I was aggressive. I drank a lot. I didn’t talk about it much. I didn’t know how to. I didn’t know what was wrong with me. I had all this f****** rage in me and it didn’t take much to kick it off, very much like my father.”

And the rage can surface again at any moment, he says, like the day he watched the film Fifty Dead Men Walking and it brought back the moment he confronted a man in the street during the hunger strike riots.

In the years that have followed, Michael has also thought deeply about what he was doing in Northern Ireland, as a soldier, and as a Scotsman, and as a socialist. In some ways, he sees the Troubles as a symptom of the British Government refusing to listen to legitimate grievances.

“When have they ever listened to grievances across the world?” he says. “When have they ever taken the indigenous population’s point of view? Typical sledgehammer tactics by the British – we will crush you before we listen to you.”

Michael also believes that as a young Scottish man, things could have been different. “If I’d been born in the Ardoyne, I would have been in the IRA; if I’d been born in a Loyalist area, I would have been in the UVF.”

Part of Michael’s way of dealing with all these questions is to throw himself in to his peace activism – he has met former members of the IRA and has been back to Northern Ireland many times. Helen Whitters is doing something similar with her mission to see the report on the death of her son. “I’m just focusing on the file,” she says.

She also often thinks about Paul and what he might be up to had he lived. He would definitely be into technology in a big way, she says, and music too. He was a big fan of the Boomtown Rats as a boy and played the penny whistle. “I just miss him,” she says. “He’s my son.”

She also values her life in Scotland, she says. There’s been sectarian trouble in Glasgow recently, she knows that, and she knows that the Scottish scars of the Troubles haven't healed yet. “But if there’s something wrong, I’m not going to ask you if you’re Protestant or Catholic,” she says. “I think we’re more positive here in Scotland, and that’s why I came back.”

The War Next Door: Scotland and the Troubles starts on Tuesday at 10pm on the BBC Scotland channel.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel