A character in American author Richard Powers' recent novel, The Overstory, says, “Best time to plant a tree, twenty years ago. Next best time to plant a tree, today.”

Tree planting today, or as soon as possible, is increasingly being recognised as a need of the moment. Given that the UK needs, the Committee On Climate Change has said, to plant 1.5 billion trees in order to meet 2050 zero carbon goals, we need many such todays. One such is set to be November 30, the Woodland Trust’s National Tree Planting Day, and the trust has called on one million people to pledge to plant a tree.

To celebrate National Tree Planting Day, we asked people to tell me stories of their relationships with trees, already growing, mature, or even lost. What came back was a flood of enthusiasm – tales of trees planted on the birth of children, of trees lost, of others saved, of putting down roots and of woodland pilgrimages.

Here are just a few:

Chris Packham, television presenter

Beech tree

"There is a beech near my home in the New Forest, which is like a pilgrimage site for me. I have cleared the ground underneath it of all the branches and twigs that have fallen. It’s become like a shrine. That is my favourite organism on earth. It’s magnificent, aesthetically, and in terms of its shape and size. It is just commanding.

"I know the woods that I walk in intimately, and I’ve probably walked under every tree in the 320 acres of woodland, and that is the best tree in the woods. It’s like I’ve got my own private cathedral. It’s just a singularly magnificent organism. I just go and sit there and think about things. Sometimes I go there just to make sure it’s okay – move any branches that have fallen down, any twigs that have got in the way. I touch the tree. I often wonder when will be the last time I see that tree.

"It has very, very definitely become part of my life. It’s part of my shared space at this point in history, and, of course, what I like about it is that I’m just a tiny bit of its history. I’m just like a gnat, flying by.

"That tree that has lived all of those years, is 550-650 years old, when you think of all the things that have happened beneath it, all the kisses, all the conversations that must have taken place. When I stand alongside that tree it really crushes any ego and any false perspectives and puts you in your place."

Gehan Macleod, co-founder of GalGael trust

Pollok Free State beech

“One special tree to me is a 200-year-old beech tree, which was down near the edge of the wood next to the Pollok Free State, the camp where we protested the building of the M77 motorway. It’s still there, and I have lots of memories associated with that tree. It sat at the edge of the Pollok Free State and was somewhere you could go for a little bit of quiet time.

"I remember one time Colin [Gehan’s husband, who died in 2005] took a book and a hammock and climbed right to the top of this tree an read for a couple of hours. When our daughter was born, we hung a baby swing there.

"I think that it was also a special tree for Colin, before I met him. I know he used to sit down there and some of the ideas that were formational in both the Pollok Free State and GalGael came to him when he was sitting at that tree, staring out at the field, reflecting. He tells the story of he had a pile of ecology magazines and he’s sitting at the base of the tree and figuring out what he was going to do in response to environmental issues. A pigeon sh*t all over his magazines which prompted him to think that this wasn’t the way we were going to reach the communities round about and pushed him towards carving as a means of communication.

"Living among the trees, and living outside in general, as I did for about a year and a half, during the Pollok Free State, had a big impact on me. We didn’t have watches or clocks. You start to tune into the daylight. You see how those trees change over time. Storms would come along and you’re lying in the woods at night, listening to all of these branches creaking and you're wondering, is something going to fall? You were aware not so much of trees in isolation, but trees as an embedded part of the environment that you’re living in.

"It often seems to me that humanity has lost that sense of connection to trees or the natural world, but also that connectedness that trees seem to represent, through their branches reaching out and their roots."

Tilouze Senni, carer

Cherry tree

"I like fruits and cherries are my favourite – but we didn’t have cherries too much where I grew up in the desert in Algeria. So, in my allotment, in the community garden, I planted a cherry tree. I would have loved to plant a eucalyptus here. When I was growing up, we used to have a really giant eucalyptus, and I used to play there with my brothers and climb it. It was an important tree. We used it to protect our cattle, cows and sheep from the sun.

"Planting this cherry tree in Scotland was about putting down roots for me. The reason I came to Scotland was to join my husband, but it didn’t work out. But there was another plant came out – my daughter – and I have stayed. The cherry tree is doing really well and growing really fast. The branches are getting very thick. Last year I got some fruits but the birds ate them.

"I believe in God and I have a really strong connection with plants. I can’t go to a place and see a plant that is not watered and not water it. For example, I’m working as a carer, and when I go to people’s houses, I do care for the person, but I find myself looking at a plant and wondering how long it has been since it was last watered. When the water just goes in there, I feel like the plant is giving me a blessing. I’m Muslim, and I believe I will get a reward after. I talk to the plant and I tell her, don’t give it to me in this life – give it to me in the life after. "

Holly Gillibrand, climate striker

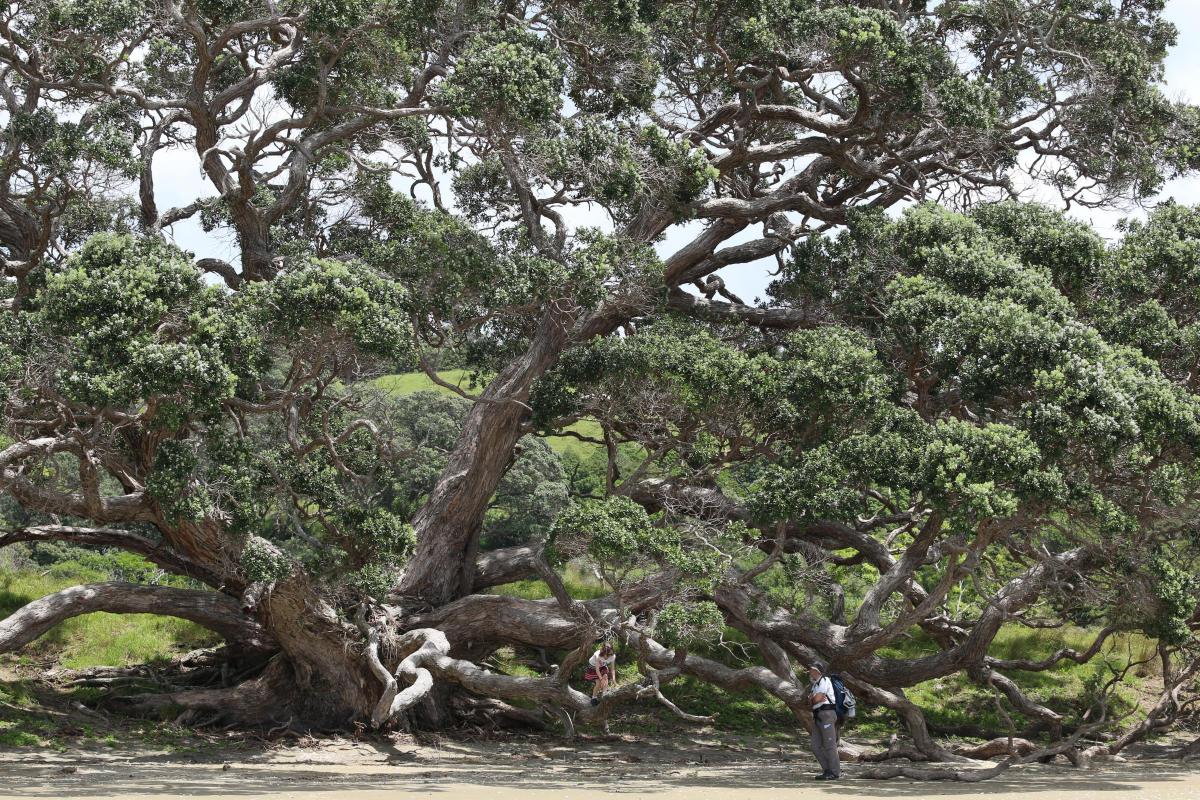

Pōhutukawa tree

"Several years ago when I was visiting family in New Zealand, I came across the biggest tree I have ever seen in my life. It towered far above the surrounding coastal landscape and being the energetic young girl that I was, I climbed it. It must have been hundreds upon hundreds of years old; weathered, battered but unbeaten. This tree was a pōhutukawa tree.

"The pōhutukawa is the New Zealand national tree and an important symbol for the indigenous Māori people. In Māori mythology, the blood of a young warrior who died while attempting to avenge his father’s death is said to be represented by the bright red flowers of the tree.

"This encounter has stayed with me ever since. It taught me how indomitable the natural world can be. But despite all efforts from environmentalists and activists, nature is in trouble. Every single Friday I strike from school to bring attention to the climate and ecological emergency and it was my connection with the natural world that drove me to start my activism.

"You cannot stand beneath a magnificent natural wonder like the ancient pōhutukawa without feeling awed at the immensity and complexity of life on Earth."

Steve Burnett, violin-maker

Arthur Conan-Doyle maple

"I’ve felt, ever since I was a kid, that trees are the lungs of the earth – a source of oxygen – mainly because from four years old onwards, I was a severe asthmatic and I was hospitalised for quite a bit of time with extreme asthma. I didn’t actually come from a musical family, but I always had a musical feeling in me. I got a chance to learn violin when I was ten, but unfortunately I was booted out after a week because I couldn’t understand the notation. But I knew as soon as I saw the violin, this beautiful object that I wanted to do something with it.

"By chance when I was nearly thirty years old, I crossed paths with a violin in a second-hand shop, and started a whole journey. I taught myself how to make violins. At one point, I started doing an instrument project with a colleague, and we thought maybe if we made a violin from a branch of a living tree at Inveresk Gardens and do a nature project with schoolkids.

"A lady, who was one of the board members at Dunedin school, saw an article about what I was doing. By chance, their tree, which Arthur Conan Doyle allegedly played in, was condemned because of diseased roots. I got a call out of the blue, and the woman asked if there was anything I could do with their tree.

"I thought it was tragic that the tree had to come down. But they said it had to because it had weak roots and it could with a strong gale come down and hit the roof. It was one of a pair of trees they think Conan Doyle played in as a boy. The other tree was saved but this one had to come down."

Judy Dowling, ancient tree hunter

Cadzow oak

"When I retired from being a nursery teacher, I started recording trees for the Woodland Trust. I had read in a book a little bit about the Cadzow oaks, a group of over 300 ancient oaks in rare medieval pasture. These oaks were not recorded in our inventory.

"So, in 2013, when I was driving up the M74 from Yorkshire, at a time when I was up and down every few weeks to see my mum, who had dementia, I decided to take a look at them. It was March and it was quite a dreich day, gloomy and dark, but I was really so fired up to see them. Scottish Natural Heritage had given me this really convoluted list of directions for how to get in, which meant I had to go down this very long single-track road. At this point it had been snowing, and it felt like madness. I was worried I was going to get stuck.

"I drove into the farmyard, saw the field with the most trees in it – over 200 trees. There’s nothing like it really in Scotland. I could see these trees in the gloaming. I went in and as I got in the middle of them, it started to snow. It was blowing a blizzard through them and there were all these black shapes, every one different, knobbled and bobbled.

"I just stood there and wept. I walked amongst them, and I thought, ‘Oh my God, none of these is recorded’, which was heaven to me."

Martine Borg, conservation horticulturalist

The Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh’s Catacol Whitebeam

"I’ve always liked rowan trees in general. They have so many folkloric associations and they are a really evocative tree. But the Catacol Whitebeam is very special because it was the only known one of its kind when the original tree was discovered on Arran in 2006 and it has taken a lot of effort to grow its clones. There are now about 20-25 of them.

"It looks quite similar to the regular Rowan, but has slightly bigger berries and this really gorgeous, dark, speckled bark. It's absolutely extraordinary that even in a country like Scotland where the flora is so well recorded, we can still discover a completely new species.

"I do think that propagating the Catacol Whitebeam is an important act for biodiversity. The big problem that we have in Scotland is that a lot of habitats are really not that hospitable for rare plants. There is a big grazing problem. To keep these genetically Scottish plants alive, we do need to grow material in cultivation.

With the Catacol whitebeam there were so many horticultural techniques we used in order to propagate it. There is only one specimen in the wild, so you have to be very careful with any material you remove from that. It’s all precious."

Tree Happy

Why do so many of us feel a special connection with trees or forests? An increasing body of research is developing around the mental and physical wellbeing effects of time spent in woods, and key in driving it in the UK, is Gary Evans, founder of the Forest Bathing Institute. Evans was inspired by research already been done in Japan, where the positive effects of time spent with trees have already been researched, and forest bathing is prescribed by doctors. “The main measurable benefit,” he says, “is the phytoncides that the trees give out, which help the trees fight off disease. In Japan, they’ve measured that it boosts the immune system, so it helps us fight disease.”

But it’s not just our immune system it helps. One Japanese study concluded that forest environments “promote lower concentrations of cortisol, lower pulse rate, lower blood pressure, greater parasympathetic nerve activity, and lower sympathetic nerve activity than do city environments.”

Evans is attempting to reproduce the scientific research done in Japan, so that it can then be prescribed in the UK, on the NHS. “We’re looking for full prescription status,” he says, “as they have in Japan, where you could be given the choice of something like blood pressure tablets or a walk in the forest.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel